The Politics of Cinematic Disposability: Jerry Maguire’s Plastic Afterlives

Tuesday, April 27, 2021 at 11:59PM

Tuesday, April 27, 2021 at 11:59PM Jeff Scheible

[ PDF Version ]

In this journal’s first issue, Joshua Neves and I brought together pieces reflecting on the video store as a “media field”: a site where media are spatially organized but also a field in the discursive, epistemological sense, in which knowledge about film history and the discipline of film studies are, or were, produced. As video stores have vanished almost entirely in the decade since then, I have been especially curious to observe what happens to videos when the video stores housing them close. Prompted by the strange story of the migration of fifty-five thousand videos in the collection of Kim’s Video in New York City (where I used to work) to the Sicilian town Salemi, I asked in a subsequent article what we might learn from studying the lifecycles of video.[1]

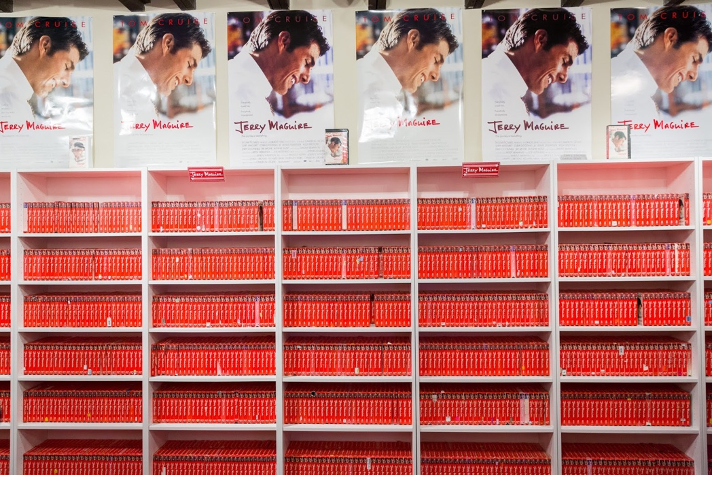

The Media Fields issue included a brief interview with members of Everything Is Terrible! (EIT!), a group of pop culture enthusiasts who manage a blog, featuring a daily clip digitized from a VHS they’ve discovered while thrift shopping or scouring closing video stores. They run various side projects too, such as curated screenings around the world and a series of performance art pieces designed to culminate in an absurdist sculpture, The Jerry Maguire Pyramid, built exclusively of Jerry Maguire (dir. Cameron Crowe, US, 1996) VHSes. EIT! set up a “Jerry Throne” at the Cinefamily theatre in Los Angeles in 2014, a “Jerry Temple” at an LA art gallery in 2015, and a full-blown Jerry Maguire Video Store at Iam8bit Gallery in 2017. The only videos in the recreated store were 14,000 Jerry VHSes. By 2020, they collected over 25,000. Their goal was to construct a pyramid of Jerry VHSes in the desert landscape of Joshua Tree National Park in 2020, though Covid-19’s disarray of everyday life has presumably stalled these plans. On their website, they explain that they have been “working with a team of architects, engineers, and builders to design this epic monument to America’s consumption.”[2] This not-(yet) realized monument begs the question: Why Jerry? And to answer that, a bigger question: Why has this particular popular film had a formidable number of afterlives in the twenty-first century?

Figure 1. Jerry Maguire video store

Figure 2. Photo by Jim Newberry

Jerry was recently referenced in an Atlantic article as exemplary of a genre that contemporary Hollywood has largely left behind: the “fun, disposable romantic comedy.”[3] The film at the same time has generated multiple quotations—“Show Me The Money!,” “You had me at hello,” “You complete me”—that have played in heavy rotation across popular culture. Television audiences might catch a glimpse of a Jerry Maguire poster hanging on the bedroom wall of Lexi Richardson, the suburban high-school senior in the miniseries Little Fires Everywhere (Hulu, US, 2020) who steals the story of her Black friend’s discrimination for her Yale application essay—an act of racial appropriation one could argue is narratively mirrored in Jerry itself. (The poster, along with the rest of the house, is burned to ash in the final episode as racial tensions prove too much for the affluent White Richardsons to handle). Few other 1990s films, if any, have simultaneously been so “disposable” yet so enduring. I seek to better understand this paradox here by exploring Jerry Maguire’s afterlives across film scholarship, media forms, and cultural phenomena.

This ongoing cinematic lifecycle offers an opportunity to reflect on consumption, plasticity, and waste, forming salient constellations of inquiry for cinema and media studies as we attune our methodologies to the intimations of the Anthropocene. At the same time, the film and its afterlives are structured by both the racialized, affective transferal of exuberance and the erasure of the racial anxieties this displacement writes over. How might we ultimately come to terms with the coalescence of the ecological and racial dimensions that tear at the seams of Jerry Maguire and its afterlives? Spiraling toward this question, this essay brings cinema and media studies into closer proximity with scholars thinking about power, inequality, and the environment. While there is a rich, growing body of scholarship on eco-cinema, much of this work remains inflected by what Kathryn Yusoff calls the “White Anthropocene.”[4] For Yusoff, too much discourse about the Anthropocene generalizes the idea of the human, in turn neglecting that it is a certain (White) raced and privileged “human” responsible for the environmental devastation and mass extinctions underway in the world’s “development.” As Laura Pulido notes, “Abundant research indicates that not only do many environmental hazards follow along racial lines, but also many of the meta-processes that have contributed to the Anthropocene, such as industrialization, urbanization, and capitalism, are racialized.”[5] How might attending more closely to intersections of—or missed connections between—race and materiality offer the field new ways of imagining our critical methods, the texts and representations we scrutinize, and indeed chart paths for rewriting film and media histories?

A key premise of my reading of Jerry’s afterlives is based in the ways it textually manages racial anxieties. While fully unpacking these would require a longer, different essay, I will try to pinpoint some important elements. I am thinking of what David Bordwell would refer to as the film’s “symptomatic interpretation.”[6] Yet Jerry’s symptomatic meanings are ignored in Bordwell’s own lengthy analysis of Jerry as a “masterpiece of tight ‘hyperclassical’ storytelling.”[7] His book’s cover image is an early scene from the film with Jerry (Tom Cruise) and Dorothy (Renée Zellweger) crammed in an elevator, facing the same direction as they avoid looking at a couple kissing next to them—suggestive of patterns of condensation he observes in the film. As Bordwell explains, “they see a deaf couple signing, and Dorothy interprets. The line itself (“You complete me”) will be repeated, but just as important, Dorothy’s ability to interpret reveals her capacity for devotion. (She learned signing in order to communicate with her favorite aunt).”[8]

This cover image, and the notion of narrational density it represents, reinforces the notion of Jerry as an intertextual site of “clichés having a ball,” as Umberto Eco once said of Casablanca (dir. Michael Curtiz, US, 1942).[9] Here, “You complete me,” like Jerry’s other catchphrases, becomes a signifier of endurability but also reducibility. Such reducibility flattens the film’s own immediate historical, societal contexts. To locate these contexts, one could begin with a different popular quote from the film: “Show me the money!,” twenty-fifth on the AFI’s “100 Greatest Movie Quotes of all Time.”[10] Taking the pattern of a call-and-response (a historically African American form), Cuba Gooding, Jr.’s character Rod makes Jerry repeat this phrase over the phone until he yells it at the top of his lungs, foreshadowing the relationship between the two throughout the film whereby Rod’s exuberance serves as a catalyst for Jerry’s emotional growth. In fact, Jerry is later only able to run back to Dorothy to tell her that she “completes” him after seeing Rod embrace his wife on the football field. Jerry’s reliance on Rod’s racialized exuberance, what Sianne Ngai would likely refer to as an “affective cousin” of “animatedness,” is the narrative’s structuring dynamic.[11] It reflects a common appropriation of Black enthusiasm by Whites in American culture, recently discussed in relation to reaction GIFs,[12] which feeds into the ongoing association of Black culture with excessive, unruly behavior, including not only exuberance but also criminality. This affective display bleeds out beyond the film as well, to Gooding’s own over-the-moon acceptance speech when he won his Best Supporting Actor Oscar, establishing what Richard Dyer would identify as a “perfect fit” with the character he played in the movie.[13]

The symptomatic reading of Jerry, a film about the White agent of a Black football player, must turn to one of the most heavily mediated events of all time, the OJ Simpson trial, televised around the clock just one year before Jerry’s release. As Linda Williams has noted, the trial’s verdict delivered a profound melodramatic twist in the saga of racial tensions dividing the nation in the years leading up to it, with George Holliday’s videotaped footage of the Rodney King beating, the acquittal of the White police officers responsible for the beating, and the 1992 Los Angeles race riots that followed.[14] If the Simpson trial became a cautionary tale for White America about the surplus of celebrity and the evil lurking behind one of the world’s biggest Black stars, Gooding’s exuberance filled the void left by Simpson’s downfall with racial reassurance. Though this context is in plain sight—consider most obviously that Gooding’s character is also named Rod—it has been remarkably neglected in discussions of Jerry Maguire, and one of my aims here is to recontextualize the movie’s enduring disposability in terms of this racial imaginary at its core.[15]

Despite its crafty script, Jerry Maguire certainly does not belong to the contemporaneous wave of mid-to-late nineties nihilistic “smart films” in American cinema influentially diagnosed by Jeffrey Sconce (think Welcome to the Dollhouse [dir. Todd Solondz, US, 1995], Safe [dir. Todd Haynes, US, 1995], and Fargo [dir. Joel and Ethan Coen, US, 1996]).[16] Its historical simultaneity with them positions it in sharp contrast. Jerry does not challenge moral values; it sustains them. The film does not contain an ounce of irony; it is saccharinely sweet and sincere, better seen as bearing a subdued, belated resonance with what Jim Collins has identified as the “new sincerity” characteristic of the early 1990s with popular films like Field of Dreams (dir. Phil Alden Robinson, US, 1989), Dances with Wolves (dir. Kevin Costner, US, 1990), and Hook (dir. Steven Spielberg, US, 1991).[17]

In more ways than one, Jerry Maguire serves as an example of what appears at the moment of its disappearance: the mid-budget Hollywood production, romantic comedy, classical style, new sincerity, the tape you’d rent from the video store to watch at home on your VCR for date night—Netflix and chilling before Netflix. Taken together, these disappearances register concurrent anxieties over the greatest disappearance of them all, the “death of cinema,” an idea that gained traction at this same time in academic and cinephilic circles. Published in 1996, the same year as Jerry Maguire’s release and on the heels of cinema’s centenary, Susan Sontag’s famous essay “The Decay of Cinema,” ignited impassioned conversations about cinema’s death. The film seems a prime example of the kind of fare that Sontag warned signaled the demise of the medium when writing that “the commercial cinema has settled for a policy of bloated, derivative film-making, a brazen combinatory or “recombinatory” art, in the hope of reproducing past successes.”[18] Crucially, as Sontag’s claim implies, the aesthetic valuation of quality is bound up intimately with nervousness over material obsolescence in “death of cinema” discourses. Nothing makes the connection between Jerry as both obsolete and “recombinatory” clearer than its recent resurrections: in Everything Is Terrible!’s ongoing Jerry Maguire Pyramid project but also in The Lego Batman Movie (dir. Chris McKay, US, 2017) where it appears as nearly the only live-action footage within the 3-D animated film.

In Lego Batman, Jerry Maguire is a cinematic fossil in an animated world, reminiscent of Hello, Dolly!’s (dir. Gene Kelly, US, 1969) invocation in Pixar’s Wall-E (dir. Andrew Stanton, US, 2008). Both of these films-within-films are suggestive of Lev Manovich’s claim that in the new millennium, live-action photography becomes one of a variety of cinematic techniques subsumed within a wider range and longer history of animation practices.[19] Early in Lego Batman, the Will Arnett-voiced Batman sits alone in a personal movie theatre in his bat cave, fidgets with two controls in his hands, and adjusts the source channel on the big screen. Scrolling down the list of options, he hovers in hesitation over different fields and finally selects HDMI 2. The screen shows the frustratingly familiar response: “No signal / Device not detected.” Remote in hand, he mumbles to himself as he then scrolls down the same list and chooses HDMI 3. In a rare departure from the film’s frenzied animated world, a photorealistic Tom Cruise as Jerry Maguire sighs onscreen, while a green volume bar rises to maximum level over the reverse shot of Dorothy’s (Renée Zellweger’s) face. The two characters look back and forth at each other in shot reverse shot, and the film cuts to Batman munching on popcorn as we hear Cruise deliver the famous line: “You complete me.” Batman erupts in laughter. We hear Zellweger reply with the perhaps even more famous line, “Shut up. You had me at hello.” Batman chuckles again, more gently, and says “I love it.”

Figure 3. Batman watching Jerry Maguire in The Lego Batman Movie (2017)

Figure 4. Live-action Jerry in Batman’s animated home theater

Vivian Sobchack notes that Hello, Dolly!’s resurfacing on videotape in Wall-E is of thematic and formal significance, serving “to overwhelm signs of ‘new media.’” Jerry’s appearance in Lego Batman is similarly suggestive of cinema’s evolving lifecycles, but if, as Sobchack notes, the DVD in Wall-E is “peculiarly absent,” in Lego Batman its digital materiality is frustratingly present, amusingly foregrounded in the dispersal of devices and overabundance of input options Batman must navigate on the screen interface to play the video.[20] As much as it is technologically marked, the citation also helps McKay tease out Batman’s emotional stuntedness—watching a familiar movie by himself, laughing instead of crying at the precise moment when the character in the film shows himself to have emotionally matured. The cinematic quotation moreover nods to McKay’s description of his Lego Batman pitch to studio executives: “Jerry Maguire as directed by Michael Mann with a lot of jokes in it.”[21] Jerry thus becomes a sort of LEGO building block within the formula of the film, in effect acknowledging Jerry itself as always already its own LEGO movie, formulaically combining clichés and pieces to fit together into an elaborate cinematic construction (for example, blending the masculine appeal and cinematic vocabulary of the sports film with the stereotypically feminine attributes and style of the romantic comedy). These issues interplay in Lego Batman with the intimation that access to the cinematic past is interactive, interfaced, and video game-like, through Batman’s use of remote controls, resembling a kid playing with toys. Indeed, the scene’s digital tactility reflexively mimics the plastic tactility of the consumer products the film laboriously but playfully animates, with scratches added to digital bricks so as to enhance their material verisimilitude.

EIT!’s Pyramid Project too foregrounds the original movie’s plasticity, not by textual emplacement but by material displacement, highlighting it as an object of consumption. As with their online endeavors, Everything Is Terrible!’s project displays an unmistakably ironic detachment, obstructing genuine engagement with the film. Ancient structures imbued with spiritual beliefs and ritualistic expectations, pyramids boast well-established connections to cinema, as elaborated by Antonia Lant and Nadia Bozak, among others.[22] By virtue of the history of its form, the Jerry pyramid announces itself as a venerative structure for a dead object. The overabundance of Jerry VHSes (according to an unverified claim on Wikipedia, it is the best-selling non-Disney VHS of all time in the US) is undoubtedly an effect of the historical contingency of the switchover to DVD that occurred soon after the movie’s release. Their project poses questions not only about the death of cinema but about the environmental consequences of media accumulation and waste, intersecting with concerns about sustainability, Anthropogenic politics, and global warming.

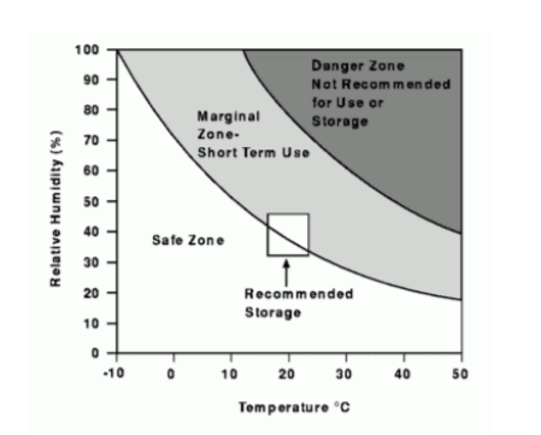

Temperatures in Joshua Tree, the desert area where they plan to erect the pyramid, for example, have an average high of 97–100 degrees Fahrenheit in summer months, not to mention uninterrupted sunshine year-round. Such weather conditions, especially the direct sunlight exposure, far exceed the Council on Library and Information Resources’ recommended storage temperatures for VHS. For playback (“access storage”), CLIR recommends storing VHS at temperatures of 15–23 degrees C (60–74 degrees F), already much higher than recommendations for longevity (“archival storage”), which are as low as 5 degrees C (or 40 degrees F) and presumably the more relevant conditions for maintaining this project’s monotonous memorabilia. Won’t the plastic of the videocassettes melt under the direct desert sunlight? What ripple effects might the toxic chromium-coated mylar and polypropylene abundant in this man-made sculpture have on the wider ecosystem in which it is erected?

Figure 5. Temperature and Humidity Conditions and Risk of Hydrolysis, from the Council on Library and Information Resources’ guide to preventing magnetic tape from premature degradation

Rather than entirely dismissing The Jerry Maguire Pyramid as ecologically irresponsible, however, it could direct our attention to questions this not-yet monument opens up, both practically and theoretically. For as many thousands of Jerry Maguires this hypothetical pyramid might contain, there are millions of other obsolete videocassettes not being repurposed into art. And where do these end up?

Heather Davis writes that plastic has “been rendered invisible due to the fact that once it is discarded, it is shipped elsewhere, at least within industrialized nations with the infrastructure to do so. It is picked up and moved away by recycling and dump trucks, shipped overseas where the material effects are displaced from the industries that produced them as well as the consumers who bought them onto other, poorer, and often racialized bodies.”[23] As levels of environmental contamination by consumer products that contain toxins with undetermined long-term effects increase, it would behoove film and media scholars to consider the ways in which our objects of study are imbricated in these cycles of consumption and waste generation. These cycles are, to put it bluntly, destroying our planetary habitus—and with uneven consequences that stage greater risks to poorer and darker-skinned global communities, or as Vijay Prashad terms them, the “darker nations.”[24] From this perspective, thousands of Jerry VHSes in Joshua Tree might seem like a small environmental price to pay.

While wildly different, these contemporary resurfacings of Jerry Maguire are both suggestive of the film’s very ambivalent status in popular culture, oscillating between loving it and laughing at it—directly as animated, plastic Batman does or indirectly as Everything Is Terrible! do. They provide occasions to think about transitional media textuality and materiality, and how these interface with, on the one hand, a broader disciplinary decentring of both the “text” and film studies foretold by “death of cinema” discourses and, on the other hand, racial politics. In largely neglecting to address Jerry’s pronounced racial imaginary, these resurfacings essentially contribute to whitewashing popular memories of the film. The examples of The Jerry Maguire Pyramid and Lego Batman (made with millions of plastic LEGO bricks) carry forward, or volley back, the question of racial displacement staged within the film if we consider where toxic plastics of which they are composed generally get displaced. “Instead of dealing with the ever-accumulated piles of plastic,” Davis suggests, we simply remove them from sight, and from consciousness, until, at least, we have reached a point where you can find wild plastic drifting along in virtually any and every environment on earth.”[25] In 2018, the year after Lego Batman was released, LEGO acknowledged the unsustainability of its mode of production, introducing into the creation of their figurines sugarcane plastic, which they pledge to manufacture with entirely by 2030. Indeed, as previous generations discard their LEGO sets and obsolescent video formats, media scholars and users alike should pay attention. And we need to consider how the environmental consequences of consumption are messily entangled with power geometries, the politics of representation, and racial capitalism.

Notes

[1] See my essay, “Video after Video Stores,” Canadian Journal of Film Studies 23, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 51–73

[2] “Everything is Terrible! Presents: The Jerry Maguire Pyramid Project,” Jerry Maguire Pyramid, www.jerrymaguirepyramid.com (accessed 12 March 2021).

[3] David Sims, “Can Netflix’s Set It Up Help Revive the Romantic Comedy?,” The Atlantic 21 June 2018, www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2018/06/set-it-up-netflix-review/563237/.

[4] Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), xiii.

[5] Laura Pulido, “Racism and the Anthropocene,” in Future Remains: A Cabinet of Curiosities for the Anthropocene, ed. Gregg Mitman, Marco Armiero, and Robert S. Emmett (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 117.

[6] David Bordwell, Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), 71–104.

[7] David Bordwell, The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2006), 63.

[8] Ibid., 66.

[9] Umberto Eco, “Casablanca, or, The Clichés are Having a Ball,” in Sonia Maasik and Jack Solomon, ed., Signs of Life in the U.S.A.: Readings on Popular Culture for Writers, 7th ed. (Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012), 442.

[10] “AFI’s 100 Years . . . 100 Movie Quotes,” AFI, afi.com/afis-100-years-100-movie-quotes/ (accessed 9 September 2020).

[11] Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005), 124.

[12] Lauren Michele Jackson, “We Need to Talk about Digital Blackface in Reaction GIFs,” Teen Vogue, 2 August 2017, www.teenvogue.com/story/digital-blackface-reaction-gifs.

[13] Richard Dyer, Stars, 2nd ed. (London: BFI, 1979, 1998), 129.

[14] See for example Linda Williams, Playing the Race Card: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001).

[15] Gooding’s casting as Simpson himself in American Crime Story: The People vs OJ Simpson (FX, US, 2016) makes this overlooked subtext all the more obvious. Gooding himself says of his performance: “I always tell people: this is the part B to my part A of Rod Tidwell from Jerry Maguire. Because I believe both these athletes have the same characteristics, that braggadocios self-confidence to overcome any adversity. One story ended positively, the other tragically.” Damon Wise, “Series Mania: Cuba Gooding Jr. in Paris on Living with the Ghost of O.J. Simpson,” Variety (23 April 2016), https://variety.com/2016/tv/festivals/cuba-gooding-jr-o-j-simpson-120175918/ (accessed 12 March 2021).

[16] Jeffrey Sconce, “Irony, Nihilism, and the New American ‘Smart’ Film,” Screen 43, no. 4 (Winter 2002): 350.

[17] Jim Collins, “Genericity in the Nineties: Eclectic Irony and the New Sincerity,” in Film Theory Goes to the Movies, ed. Collins, Hilary Radner, and Ava Collins (New York: Routledge, 1993), 242–63.

[18] Susan Sontag, “The Decay of Cinema,” The New York Times, 25 February 1996.

[19] Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001).

[20] Vivian Sobchack, “Animation and Automation, or, the Incredible Effortfulness of Being,” Screen 50, no. 4 (Winter 2009): 380.

[21] Mike Ryan, “Director Chris McKay Shares the Secrets Behind The LEGO Batman Movie,” Uproxx, 2 August 2017, uproxx.com/movies/the-lego-batman-movie-chris-mckay/3/.

[22] See for example Antonia Lant, “The Curse of the Pharaoh, or How Cinema Contracted Egyptomania,” October 59 (Winter 1992): 86–112; Nadia Bozak, The Cinematic Footprint: Lights, Camera, Natural Resources (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012), 135–138.

[23] Heather Davis, Plastic: The Afterlife of Oil (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, forthcoming), 11.

[24] Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (New York: New Press, 2007).

[25] Davis, Plastic, 11.

Jeff Scheible teaches Film Studies at King's College London. He is the co-editor of Deep Mediations: Thinking Space in Cinema and Digital Cultures (2021) and the author of Digital Shift: The Cultural Logic of Punctuation (2015), both published by University of Minnesota Press.