The Presence of Others Affects Me: On the Mutuality of Cinema and BitTorrent Piracy

Friday, January 19, 2024 at 2:58PM

Friday, January 19, 2024 at 2:58PM Sudipto Basu

[ PDF Version ]

Figure 1. Spectators at Invisible Cinema at Anthology Film Archives, New York, 1971-74. Photo credit: Gamze Yeşi̇ldağ, “Invisible Cinema, A Movie Viewing Machine”, Dry Clean Only Magazine (Dec 2020). https://drycleanonlymagazine.com/en/invisible-cinema-a-movie-viewing-machine/.

Invisible Cinema and the Disappearing Collective

The experimental filmmaker Peter Kubelka’s design for an Invisible Cinema—first realized in the Anthology Film Archives in New York from 1970-74—offered an oddly specific apparatus for spectatorship, aiming to eliminate all peripheral distractions and concentrate the viewer’s attention solely on the screen. Kubelka wanted “to make the screen [the viewer's] whole world, by eliminating all aural and visual impressions extraneous to film.”[1] The ceiling, walls, and seats were covered in black velvet, and everything was dark except for minimal exit signs and aisle lights. The approximately ninety seats, arranged in rows on a steep gradient, were designed like isolated pods with partitioned side blinders and high backs such that no one could see or hear their neighbors. Viewers were prevented from entering or leaving the theater once the show started and were strongly discouraged from talking or making noises. Kubelka’s design insisted that “the cinema's function was to bring ‘the filmed message from the author to the beholder with a minimum of loss’; the film should ‘completely dictate the sensation of space.’”[2]

While no doubt an extreme design to generate an immersive experience, Invisible Cinema was, in a sense, the epitome of a wider tendency in film criticism and theory which treats spectators as individualized subjects in an uninterrupted relationship with the filmic text. Think of contemporaneous currents in apparatus theory concerned with the spectator’s ideological interpellation into the gendered, hegemonic matrix of power in capitalist societies. Or think of film criticism concerned with close textual analysis, where the privileged locus of meaning is on screen, in the axis of sight that connects the film with the spectator. The spectator, mind you, not viewers (plural). What is absented in this mode of writing—or dismissed as negligible background—is the act of viewing together, as part of a collective in the same physical space. What gets written out of the process of meaning making and cinematic experience are a range of collective affects and emotions: the occasional irritation (the neighbor who laughs too loud), the fannish enthusiasm of in-groups (who excitedly share internal references and codes), or even the contagion of affects (laughter, horror, or nervous anticipation that ripples through the audience). This is not even to speak of the many geographical and historical contexts where the subdued, disciplined spectator assumed by apparatus theory and textual analysis does not hold; in these cases, cinematic experiences and meaning-making are jubilantly collective and shaped offscreen, in the space of exhibition. Think of the fairground-like contexts of early cinema around the world before feature-length narrative films became a standard—what Tom Gunning called the cinema of attractions. Or consider the blockbuster star vehicles of India, whose screenings are often accompanied by quasi-religious pomp, devotion, and ritual worship of stars, with fans boisterously singing, cheering, and dancing along to the film.[3]

Mutuality in the Dispositifs of Cinema

There has always been this mutual implication of viewers in cinema, this relation of bodies and subjects to each other in the space of exhibition—arguably so even for Invisible Cinema. Kubelka designed the chairs to allow viewers to touch others, if they so wished, with the intention to create a “sympathetic community.”[4] Mutuality here lay in respectful silence and shared appreciation for film as an art. In a very different sense, we are also mutually implicated now on video on demand (VOD) platforms like Netflix through algorithms that track our smallest actions to push personalized recommendations, filter content, and recursively shape the platform’s acquisitions and production decisions.[5] With VOD, the impatient shuffling of others that so bothered Kubelka is integrated as feedback into a cybernetic cinematic apparatus. This implies an ambient ethico-political relation with others since our personal behaviors shape the landscape of possibilities for everyone else, pushing certain kinds of content down (or out) in lieu of others.

Therefore, our mutual implication as spectators extends today from the site of exhibition into the spheres of cinema’s distribution. But in this essay, instead of corporate streaming platforms, I am interested in a pirate technology—torrenting—that predates the cultural turn towards commercial streaming and continues to be significant for a large number of cinephiles.[6] For me, film piracy in cinephilic communities raises the question of mutuality even more strongly than commercial streaming, given its opposition to the mainstream. While streaming runs on large industrial apparatuses that allow for disengaged consumption, piracy-based cinephilia calls upon users to foster a film culture that often would not exist widely without their intervention and active participation. From older practices of bootleg VHS, CD, DVD, and hard disk trading, to torrenting and direct download networks online and today’s shadow libraries of Vimeo, Mega or Google Drive links and Telegram channels, there’s a long history of mutualist film distribution and cinephilic archiving that interests me here.

Understanding Media Piracy from Within: The Technopolitics of Filesharing on Torrents

Most humanists working on media piracy have argued for piracy’s practical necessity for the production and circulation of media cultures and preservation of knowledge commons. They show how pirate cultures disrupts the hierarchies of tiered access, the cult of capitalist originality and innovation, and the transnational divisions of labor that underpin media production and circulation through copyright, digital rights management (DRM) and geoblocking systems. They have tied piracy to the uneven, differential experiences of modernization especially in the Global South, to informal economies of commodity/cultural production and consumption.[7] In a time of massive platform capture by media corporations, these piracy debates wage an important fight in leveling techno-cultural lags between Global North and South and giving ordinary users a greater say in production and consumption. Specifically in the case of cinema, piracy networks like Karagarga (that I discuss later) fulfills a role in cultural curation and archiving that more formal initiatives adopt only later.[8]

But these ethico-political debates nonetheless take up, I believe, an extrinsic view of piracy. To understand the mutuality that underpins pirate economies, we need to pay closer attention to the specific technopolitics of sharing immanent to particular technologies or protocols. How is mutuality mediated by technosocial protocols or norms? How do specific models of piracy networks and social-technical forms influence archival coverage, file sustainability, and distribution of labor? How do these models reinscribe or undo differential access to various kinds of users? Who are the ideal users of a piracy technology? Let us turn to torrenting to understand these questions. As a peer-to-peer (P2P) technology, media files in torrents are not stored in any central server but copied bit by bit from one peer to another. A torrent tracker like The Pirate Bay (TPB) acts as an index of files and helps coordinate fragmented file transfers between seeders and leechers in any swarm (pool of users sharing a file). Though this method helps in evading litigation and server takedown, its drawback from an archival perspective is that file availability requires seeders to be always present in the swarm. The vitality of a torrent commons thereby lies with its users and their willingness to constantly upload and seed files. But for cinephiles interested in rare or old films, public trackers are in fact “vast content graveyards” of dead torrents, and many titles have never even been indexed.[9] This is partly due to the inherent bias of public trackers towards mainstream-popular content tied to hype cycles, but it is also caused by their dominant division of labor through warez scenes (organized pirate groups) that do the bulk of uploading and seeding—while most lay users in a swarm quickly move from one popular torrent to the next, merely leeching.[10] Torrent descriptions sometimes urge users to seed 1:1, but without any enforcing mechanism, archival robustness—the long-term preservation of cultural material—is uneven and ineffective.

Karagarga: A Cinephilic Workers Council

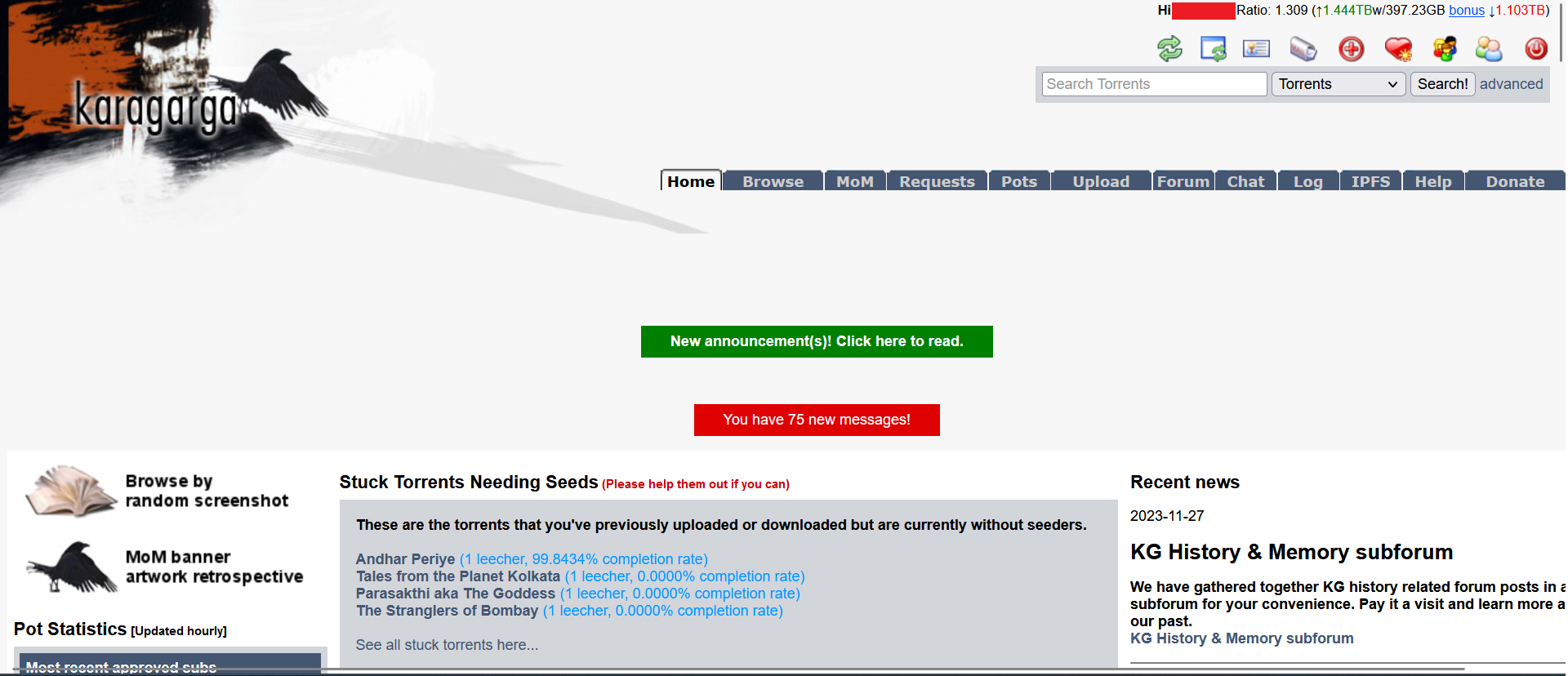

Figure 2. Landing page for Karagarga, showing elements like a user’s ratio, upload and download volume etc. on top right corner. Screengrab by author.

Figure 3. KG ratio and downloading rules, from the Rules page. Screengrab by author.

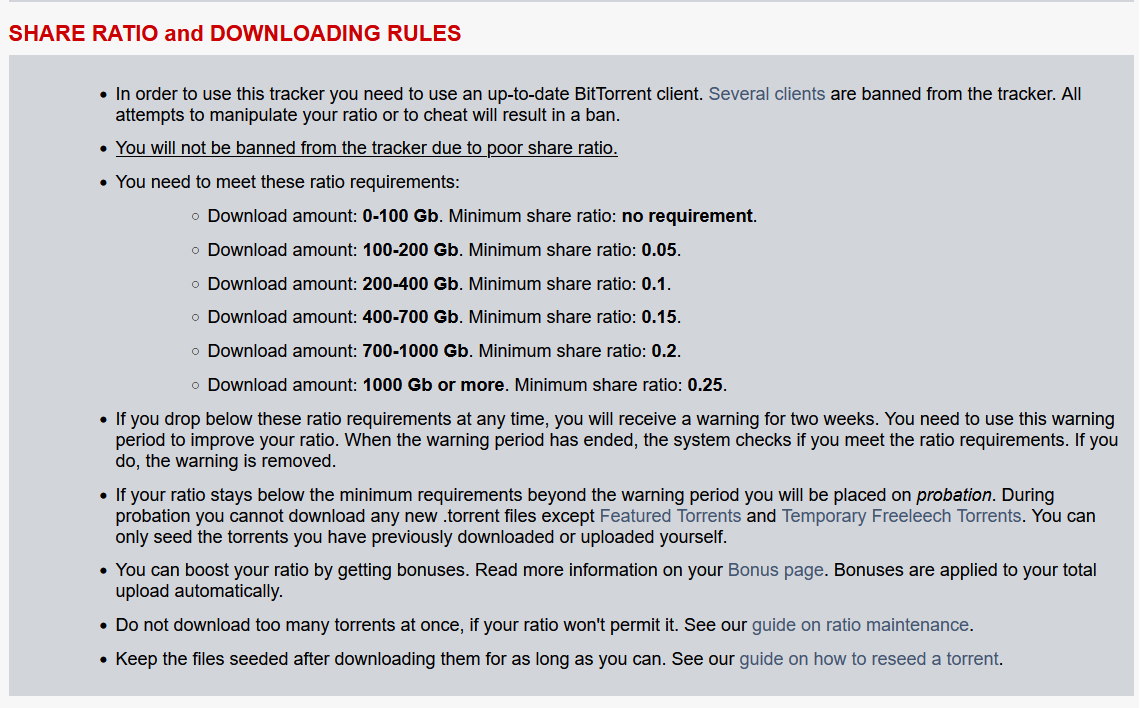

This fragility of archives on public torrents has prompted the creation of private trackers: torrenting networks that establish discretionary signup policies or ratio requirements to inculcate seeding as a responsibility.[11] Karagarga (KG), a widely known (if secretive) private tracker dedicated to alternative, classic, and experimental cinemas, is exemplary in this regard.[12] Through rigorous rules such as a ratio and bonus system (that encourages users to seed, upload new material, and create collections or subtitles), stringent quality criteria for rips, and a ban on duplicate uploads, KG institutes a labor-centric reciprocity or mutual indebtedness into its community of users. A user’s ratio is the total upload volume (plus bonuses) divided by total download volume across their entire activity on the tracker. By enforcing ratio requirements, KG intends to deter the unequal distribution of pirate labor so pervasive in public torrent trackers. KG’s tightly rule-bound space thereby ensures the durability and wide coverage of its archive.[13] Its rules do not just have to be read upfront by a new user, as the service is unusable otherwise. Rather, they are encoded into its very technological protocol through ratio and bonus tracking bots and norms of practice, which moderators play a huge role in enforcing.

If public trackers like TPB were designed for the open, free libertarian swarms of 90s cyberculture, KG institutes an insular society of worker-cinephiles around the valorization of labor and shared goals. Far from the anarchic vision of piracy we associate with PirateBay (and the Swedish piracy movement at large) or statist depictions of pirate cultures, KG offers an example of a hyper-structured economy or society with its own set of norms, rules of exchange, and enforcement mechanisms. While KG’s manifesto likens itself to a municipal library, we could even compare it with Kubelka’s Invisible Cinema or the film societies formed during the high point of interwar modernism that created the first cinematheques, festivals and archives.[14] Like municipal libraries, KG demands discipline and quiet sympathy—a deference to community rules and moderators—and prioritizes lack of clutter and noise. Unlike TPB, there are no spammy interfaces or text descriptions. Rather, as in Invisible Cinema, its architecture enforces this disciplined mutuality. But KG’s valorization of cinephilic labor also resonates with the pride that an earlier generation of film society activists took in organizing screenings, editing journals, or carrying film cans from the embassy or cinematheque.

While the KG economy is non-monetary and trading for money is prohibited, ratios functions as a kind of inside-currency and “labor incentive” within its economy, segmenting users into various ranks.[15] High ratios allow a user the freedom to download more files, request specific content or subtitles, etc. On the other hand, if someone’s ratio drops below the minimum, they lose access to download. It is symptomatic of KG’s broader insistence on the labor of engagement: members can’t use it merely as a one-sided service to get rare films; they have to work to sustain the pirate commons. While BitTorrent communities have been understood as online gift economies, they are not based on one-to-one mutual reciprocity. Rather, they are made of weak social ties. What matters are population scale probabilities in the network: failure of individual peers does not matter so long as there are other peers to route and seed data. Here, ratio as a technosocial protocol guarantees the sustainability of the P2P film archive—ensuring enough seeders are seeding a file—while concretizing the social obligations, norms and privileges embedded in KG’s inherently social form of file sharing. This technological protocol enforces what I am calling disciplined mutuality, the imperative to share and be present for others, to be good worker-citizens.

At the same time, ratio—and the labor-centric social organization it concretizes—builds in forms of hierarchy and exclusion that seem antithetical to the spirit of a pirate commons for internationalist film culture, locking up the riches of film history within a walled garden. Not only is joining KG hard, invitations to sign up are also very selectively given out by KG users to a few friends they trust, usually other cinephiles. The ratio economy also makes us ask: who has the necessary time to engage in this labor, the computing and financial resources to store many films on hard drives and seed (or buy a seedbox), the tacit knowhow to source new and rare material, the technical knowhow to make rips and subtitles, and so on? Though no overt markers of race, class, gender, and location determine entry and social mobility within the KG economy, it implicitly excludes users without access to stable broadband internet, those with busy work schedules or family duties, the non-tech savvy or casual user, etc.[16] Arguably Global North/South divides between KG users also creep in according to what kinds of tasks users perform to maintain their ratio: users in the developed West have access to a much larger pool of new DVD/BluRay releases to rip and upload, while those in the South mostly have to dip into informal networks of screeners and library collections or make subs to keep their ratios high. These hierarchies trouble our preconceptions about some of the larger ethical and political questions surrounding pirate commons—who gets to access what kind of culture, and for what cost? Who is inherently excluded from this apparatus of disciplined mutuality?

Conclusion

In Seeing Like a State, James C. Scott admonishes high-modernist ideologies of technological progress that were single-mindedly adopted by twentieth century nation-states, including socialist regimes, for being authoritarian and simplistic. For Scott, they perpetuate much social and ecological violence by homogenizing complex lifeworlds. Instead, he champions an anarchist-influenced ethic of mutuality (metis) that is more horizontal in its social structure, egalitarian, ecologically diverse, resilient, and above all opposed to the monolithic logics of state-formation. However, I suggest, KG’s case shows us that hierarchical structures and ethics of mutuality are not necessarily opposed; neither are high-modernism and autonomous collectivities.[17] If we understand KG in the high-modernist lineage of twentieth century activist film societies—defined by the cultural mission of fostering an internationalist film culture beyond the capitalist mainstream, beyond uneven copyright regimes—we must reckon at the same time with the paradoxically disciplined and hierarchical architecture that enables this mission. Once one is dealing with a sufficiently large population of users, mutuality can no longer rely on an interpersonal obligation to ensure that sharing is sustained. An impersonal, technological mediation of mutuality like KG’s ratio and bonus system and rules-based architecture becomes necessary. This is particularly essential to more equitably distribute the kinds of labor and resources needed to maintain a peer-to-peer film archive dedicated to rare and alternative content even if hierarchies and divides creep back into the social form on some level. At the same time, this enforcement of rules is only possible with a certain size of user populations: KG’s user base numbers around 16,000 and already draws on a large amount of unpaid moderation labor, remunerated only indirectly through ratio or rank. A much larger pool of users would almost certainly become unmanageable. In these aspects, KG seems to parallel Invisible Cinema again: not only does it need an architecture to enforce a disciplined mutuality, but this disciplining can also only be achieved within a certain limited size and context (a ninety-seat room in the Anthology Film Archives) where a niche user population is already inclined to acquiesce to these strictures. Simply put, these restrictions would not likely hold in a wider ‘outside world.’ Perhaps it is the very seclusion and tacit stratification of this architecture that enables the pursuit of a high-modernist cinephilic mission.

Notes

[1] Sky Sitney, “The Search for the Invisible Cinema,” Grey Room 19 (Spring 2005): 103.

[2] “Julian Hanich, “The Invisible Cinema,” in Exposing the Film Apparatus: The Film Archive as Research Laboratory, ed. Giovanna Fossati and Annie van den Oever (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016), 348.

[3] S.V. Srinivas, “Whistling Fans: Reflections on the Sociology, Politics and Performativity of an Excessively Active Audience,” The IUP Journal of History and Culture V, no. 3, (2011): 34-54, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2064573; Uma Maheswari Bhrugubanda, “Embodied Engagements: Filmmaking and Viewing Practices and the Habitus of Telugu Cinema,” BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies 7, no. 1 (2016): 80–95, doi: 10.1177/0974927616635944.

[4] While the senses of sight and sound were delimited in Invisible Cinema, Kubelka encouraged tactile communication. He wrote: “The sense of touch maintains community, as in earlier times.” Quoted in Hanich, “The Invisible Cinema,” 351. Tactile communication may have been grounding and necessary especially for immersive and disorienting kinds of experimental cinema—like Stan Brakhage and Michael Snow’s work or the ‘flicker films’ by Tony Conrad and Paul Sharits. Many reported a sensation of “floating in black space” heightened by Invisible Cinema’s architecture.

[5] For an overview on how Netflix algorithms track the minutiae of user data, and filters recommendations based on thousands of microtags that position both existing and future works in a landscape of fine-tuned microgenres, see Ed Finn, “House of Cards: The Aesthetics of Abstraction,” in What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of Computing (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017), 87-112.

[6] There is a growing literature on this. See Finn, “House of Cards: The Aesthetics of Abstraction”; Mattias Frey, Netflix Recommends: Algorithms, Film Choice, and the History of Taste (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2021); Elena Pilipets, "From Netflix Streaming to Netflix and Chill: The (Dis)Connected Body of Serial Binge-Viewer," Social Media + Society (2019): 1–13, doi: 10.1177/2056305119883426..

[7] Patrick Burkart, Pirate Politics: The New Information Policy Contests (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014); Ravi Sundaram, Pirate Modernity: Delhi's Media Urbanism (New York: Routledge, 2010); Ramon Lobato, Shadow Economies of Cinema: Mapping Informal Film Distribution (London: BFI/Palgrave Macmillan, 2012); Silvia M. Lindtner, Prototype Nation: China and the Contested Promise of Innovation (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020).

[8] See, for example, the recent work of the Missing Movies group, which aims to preserve a richer diversity of film history on streaming platforms against corporate obsolescence: http://missingmovies.org/.

[9] For a study on TPB’s low file sustainability, see John D. Martin III, “Piracy, Public Access, and Preservation: An Exploration of Sustainable Accessibility in a Public Torrent Index,” Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 53 (2016): 1-6, doi: 10.1002/pra2.2016.14505301123.

[10] Unnamed, "Insider Perspective: The Warez Scene", in The Pirate Book, eds. Nicolas Maigret and Maria Roszkowska (Ljubljana: Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Art, 2015), 43-63, http://thepiratebook.net/.

[11] Ratio is the total volume of data uploaded (seeded) by total volume of data downloaded (leeched) by a user. Some trackers like KG add bonuses to upload data, encouraging users to do things that get them bonuses. If a user’s ratio falls beneath a certain level, they have to boost their ratio up to required limits or risk getting deactivated or even kicked out.

[12] Karagarga’s cultish popularity is evident in its Urban Dictionary entry: https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=Karagarga. It has also received some attention from cultural critics and journalistic outlets interested in digital archiving of rare films. See Lukas Oscar Lacey-Hughes, “The Case of Karagarga,” Isis, December 2022, https://isismagazine.org.uk/2022/12/the-case-of-karagarga/; Dan Schindel, “Can Pirates Help Save Nonfiction Works?,” Immerse, 9 March 2022, https://immerse.news/can-pirates-help-save-nonfiction-works-cc061b062ceb; and, “Karagarga and the Vulnerability of Obscure Films,” National Post, 3 July 2015, https://nationalpost.com/entertainment/weekend-post/karagarga-and-the-vulnerability-of-obscure-films..

[13] Because new uploads cannot just be repeats of already existing torrents, and users must still keep up their ratios, the ban encourages them to add rarer, newer material. KG’s film library thereby expands continuously..

[14] For more information on the film societies, festival and discursive established during the high point of interwar modernism, see chapters three and four, Malte Hagener, Moving Forward, Looking Back: The European Avant-garde and the Invention of Film Culture, 1919-1939 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007).

[15] Stephen Russell, “KaraGarga: Cultural Capital and Leisure/Labor in an Online Cinephilic Community,” Mysterious Objects, not dated, https://www.mysteriousobjects.com/karagarga-cultural-capital.html, accessed 26 November 2023.

[16] The actual demographics of KG’s user base are hard to determine since no personal data is collected and all users are anonymous. However, some facts may be intuited through more informal modes of surveying the self-reported regions/countries of the anonymous users.

[17] James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998). See chapter 9 for his discussion of anarchist mutuality.

Sudipto Basu is a PhD student in Film and Moving Image Studies at Concordia University. He studies how theories of media and technology shaped Cold War-era developmentalist experiments in the Global South (with a special focus on India) and how technocratic modes of governance thwart political transformations for subaltern populations. He is a research associate on the SNSF-funded project Governing Through Design, and edits the online research portal Against Catastrophe.