Nostalgia as an Agent in the Life Cycle of Media

Saturday, May 1, 2021 at 12:01AM

Saturday, May 1, 2021 at 12:01AM Dominik Schrey

[ PDF Version ]

In 1995, Bruce Sterling and Tom Jennings initiated the so-called Dead Media Project, a mailing list for the collection and description of “dead” media technologies and their respective functions, mechanisms, and areas of application. The list includes both optical devices that seem obscure from today’s point of view and a series of digital computers and electronic video games from the immediate past that are no longer in production. Initially, the aim of the project was to publish a handbook, but this idea lost momentum and eventually died. Even though the authors intended their initiative as a memento mori during the heyday of the fascination with what was then still emphatically called “new media,” it was also a romantic undertaking, urging us to mourn all that has passed away and can be salvaged only by means of narrative. Today, not much remains of the project once launched as an archive for everything lost in the process of media change: There is an entry page to a website whose layout evokes memories of Netscape Navigator and AOL trial subscriptions; a series of dysfunctional hyperlinks; a collection of short Wiki-articles; and a steadily growing number of mentions of the undertaking in media archaeological publications, which insist that these supposedly dead media haunt our contemporary media culture as revenants in one form or another.[1]

Figure 1. Screenshot of the official homepage of the Dead Media Project, www.deadmedia.org

While the Dead Media Project did not survive the fast-moving nature of the digital age, it contributed to an understanding of media history that can be described as a “nostalgic historiography” that partakes in the organic metaphor of media life cycles.[2] Here, I explore this nexus. While there have been many nostalgia-themed monographs, edited volumes, and special issues since the publication of Katharina Niemeyer’s seminal Media and Nostalgia, the role nostalgia plays as a driving force in media history and its narratives are not widely discussed.[3] A noteworthy exception is Simone Natale and Gabriele Balbi’s “Media and the Imaginary in History,” which I briefly outline before offering a modification to their model.[4] While the heuristic simplicity of their historiographic model deserves critical discussion, the goal of my endeavor differs. I understand nostalgia as a complex phenomenon that is not necessarily “directed toward the past . . . , but rather sideways.”[5] I reconsider the role of nostalgia as a significant agent in all three stages of the media life cycle.

Natale and Balbi’s Three-Stage Model

Natale and Balbi describe the life cycles of media as following a three-stage model, assuming that different perspectives dominate the perception of each phase. The first stage (“Before the Medium”) begins even before the actual “invention” of new media technologies and consists primarily of more-or-less tangible speculations and fantasies about how the future of media technology might look. In retrospect, these “imaginary media” should not be understood as prophecies to be validated for the current situation, but rather, as an engagement with an earlier one, the authors emphasize.

The second phase (“When the Medium is New”) is a period marked by both euphoric and dystopian projections of the developments driven by innovation. Depending on perspective, the new is imagined as a solution for existing problems or a cause for future ones. Especially at the beginning, this second phase is, therefore, a period of interpretative flexibility in which the specific forms of use and potentials of new media are negotiated. “Many of these early visions and uses of new media will disappear in later stages, others will yield secondary and alternative uses of these or other media, and only a few will be part of the dominant identity of new media—becoming, in a word, mainstream.”[6] Media historiography, according to Natale and Balbi, traditionally deals primarily with this second phase, usually focusing on the aspect of innovation. Even “old media,” they argue, are viewed almost exclusively in this form: as earlier “new media,” whose former innovation is now examined in retrospect, while they have already entered the third stage of the model.

The institutionalization is complete in the last phase of the “life cycle” (“Fantasies of Obsolescence and Death”). Specific social and cultural functions are now stable. Nevertheless, the imaginary still plays a central role in this phase, but now mainly appears in the form of prophecies about the supposedly imminent death of the medium or its threatened displacement into insignificance by newer technologies. An example of this context is the claim of an imminent “death of film” repeated with astonishing regularity.

As this example shows, such obituaries are usually misguided, or at least premature. In this third phase of completed institutionalization, media technologies often prove to be quite flexible. Secondary functions and practices can become primary ones again; new or discarded forms of use are (re)discovered and artistically explored.[7] An example of this “reinvention” of a seemingly obsolescent medium would be the cultural practice of turntablism that emerged in the early 1980s at the same time as the digital Compact Disc (CD) was introduced to the market.

Likewise, processes of “re-enchantment” of established technologies occur in the third stage of the life cycle, as Tom Gunning points out in a similar context.[8] Whereas he only mentions nostalgia in passing, Natale and Balbi detail its role and describe it as a central characteristic of the third phase of their model: “When a new medium partially or completely supplants [an old] one, mechanisms of emotional affection and nostalgia can arise . . . , with the older technologies being re-interpreted as more fascinating or authentic.”[9]

Nostalgia as Inverted Utopia

While contemporary cultural theory discusses nostalgia as increasingly complex and multifaceted in the wake of Svetlana Boym’s The Future of Nostalgia, media historiography tends to one-dimensionally associate nostalgia with escapism or kitsch, denouncing it as a regressive tendency. As Stuart Tannock asserts, these negative connotations lead to the result that nostalgic narratives supposed to be understood as progressive or critical are usually characterized by different, more positive terms like “utopian.”[10] In the same vein, Nicholas Dames writes that a “strong hermeneutic of suspicion . . . refuses to succumb to the blandishments of nostalgia, and prefers instead to detect the manipulations of power behind those potential seductions.”[11] Against this backdrop, it is hardly surprising that media historiographers often explicitly dismiss nostalgia as a source of motivation or perspective.[12] Especially in media archaeological studies, this rejection is common—this is remarkable considering the “decidedly Romantic” nature of the approach.[13]

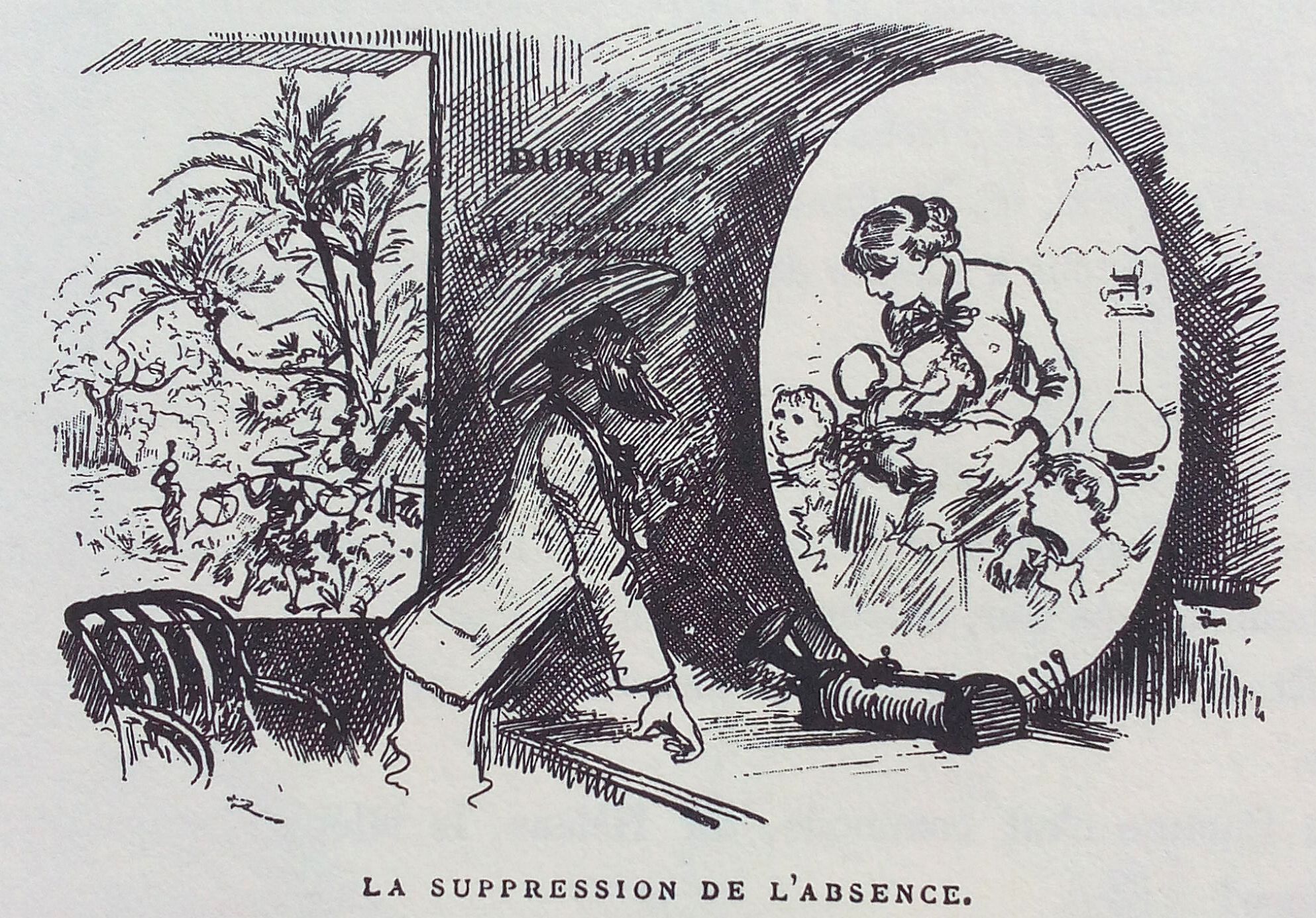

However, nostalgia is not only a strong motivation within media historiography, as I have shown elsewhere, but is also a force within media history itself, as I argue here.[14] The imaginary media of science fiction and other fantastic genres that are pivotal for Natale and Balbi’s first stage, for example, often exhibit a distinctly nostalgic dimension when we understand nostalgia as a historically inverted utopia.[15] Many futuristic media utopias, on closer inspection, turn out to be vehicles for a notion of technological progress as a return to a more direct, less mediated form of exchange (think, for example, of the idea of cyberspace.) Imaginings of radically new communication technologies are typically described as more natural or holistic than their predecessors. They allegedly overcome the disturbing aspect of imperfect mediation and bring the participants back to the idealized form of face-to-face communication, or an unmediated experience of reality, as in this famous illustration of Albert Robida’s Le vingtième siècle (1883) which promises a “suppression of absence.” This deeply colonialist fantasy also presents an imaginary technological solution to nostalgia in its original meaning of homesickness.

Figure 2: Illustration of the imaginary ‘téléphonoscope’ from Albert Robida's Le vingtième siècle (1883)

In the course of the institutionalization of media technologies, however, we can often observe a reversal of this perspective. The realization that the desired increased immediacy is only possible at the price of an equally increased technical intervention may lead to the conviction that older—and thus usually technologically less complex—media are of a less mediated nature, or at least are more predictable in their mediation. We also usually find residues of such “utopian media nostalgia” in the second stage of the life cycle. For example, this is apparent in the context of the euphoric adoption of new media that often builds on the fantasies of immediacy coined in the first stage. Advertising for new media devices, for instance, often makes recourse to established metaphors of magic to illuminate their newness and to stir a primordial sense of wonder:

Figure 3: Advertisement of Farnsworth Television and Radio Corporation, 1944

More importantly, we can characterize the processes of remediation that are characteristic of the early stage of institutionalization as nostalgically motivated.[16] In order to gain acceptance and become institutionalized in the first place, new media often emulate the look and feel of older media technology’s interfaces. So-called skeuomorphic design has been extensively analyzed in the context of nostalgia and retro aesthetics in the last years—so much so that other aspects might have fallen from view.[17]

Metaphysical doubts

The dystopian dimension of a technophobic rejection of new media forms also frequently builds on nostalgia, albeit in this case, on a restorative nostalgia in the sense of Boym. From this perspective, new media do not only threaten established media, but they also challenge the values that existed in their time. In theoretical accounts of dealing with new media technologies, this often leads to the conviction that these values need to be protected against the dangerous and pernicious influences of new media.[18] We find narratives of loss and decline in the context of every significant change in cultural mediation through technology: from Plato’s criticism of the cultural technique of writing[19] to the concerns about the loss of the soul allegedly still present in handwriting and lost in mechanical printing processes,[20] to the prominent complaints about the hyper-real “phantom world of television,”[21] to the academic fears of a loss of reality in the course of digitalization.[22]

While these pessimistic narratives differ in detail, they share a self-presentation that seeks to unmask the communication utopias associated with new media or cultural techniques: The written word, for example, is capable of externalizing memory, but only at the cost of the human capacity of remembrance. At a second glance, a development initially presented as supposed progress thus turns out to be a process in which loss predominates. In many cases, such a “nostalgic media historiography” may be rooted in general cultural pessimism; in other cases, it may be rooted in a specific notion of humanistic literacy, which appears to be threatened by new media forms that are supposedly less suitable for conveying high cultural content.[23]

Frequently, however, there is a fundamental metaphysical doubt at play, referring back to the utopian imagination of the first stage that Natale and Balbi describe. This doubt takes various forms. Hartmut Böhme, for instance, draws attention to the fact that prevailing conceptions of media history are based on the assumption of a shift from the dominance of written culture to the dominance of audiovisual culture.This implicit model, he contends, builds on a hidden metaphysics of writing according to which the medium of writing, though technical in its very nature, is in a truthful contact with reality because the world itself is a product of writing, or presents itself as scripture.[24] This theological view became popular with the idea of the liber naturae (the book of nature). This notion presupposes writing as essentially unmediated. Building on that premise, all further developments in media history are conceptualized as an ongoing process of alienation from this supposed ideal state. There are prominent traces of this idea of a liber naturae, in which creation reveals itself, in Siegfried Kracauer’s Theory of Film, a text that insists on the primacy of the visual. According to Kracauer, the potential and, ultimately, the purpose of film is to present reality in its “raw state”—unmediated, as it were. Whether films succeed in achieving this goal, however, significantly depends on the “ability of their creators to read the book of nature.”[25]

Another variant of this nostalgia for a primordial immediacy is expressed in the idea that media artifacts contain a certain degree of “being”[26] of those communicating through them, or of that which is represented in them, whereby this metaphysical added value decreases with each further step of medialization.

Figure 4: Advertisement of the American Federation of Musicians (1930)

Jonathan Sterne discusses this idea as “metaphysics of recording.”[27] Criticizing a supposed “loss of being” instigated by new media technologies is an old topos, as Sterne asserts. However, in the twentieth-century “writers accepted the basic fact of mechanical and electronic media, and so the critique that copies lose some essence of the original has been displaced into a debate about the relative merit of one kind of copy versus another.”[28] When reality itself is perceived as no longer directly accessible, there are at least older media technologies whose mediating intervention is experienced as lower than that of their successors. They—or the contents communicated through them—can therefore appear more authentic in this perspective since they seem to be closer to the assumed original of unmediated communication. This way, authentic experience is stylized into what Walter Benjamin describes as “the Blue Flower in the land of technology.”[29] While the relevance or the possibility of such an experience is questioned, it persists as a site of longing.

Conclusion

Natale and Balbi’s three-stage model provides a useful tool to analyze media change through the lens of innovation and obsolescence. The model describes nostalgia as a phenomenon of the last stage and associates it with (often premature) fantasies of a medium’s imminent death. However, as I argue, nostalgia also plays an essential and multifaceted role in the first two stages. Many utopian speculations about future media technologies turn out to imagine a return to unmediated or less mediated communication. In the same vein, the pessimistic or dystopian accounts criticizing new media often display a distinct nostalgia for older media (or the standards associated with them), sometimes rooted in metaphysical deliberations. Reconsidering the significance of nostalgia as an actor in all three stages allows us to recognize recurring “topoi” of media historiography.[30] More importantly, it enables us to emancipate the heuristic metaphor of the life cycle of media from its roots in what White calls “nostalgic historiography.”

Notes

[1] Garnet Hertz and Jussi Parikka, “Zombie Media: Circuit Bending Media Archaeology into an Art Method,” Leonardo 45, no. 5 (2012): 424-430.

[2] Hayden White, Metahistory. The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe,(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975), 145.

[3] Katharina Niemeyer (ed.), Media and Nostalgia: Yearning for the Past, Present and Future,(Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

[4] Simone Natale and Gabriele Balbi, “Media and the Imaginary in History: The Role of the Fantastic in Different Stages of Media Change,” Media History 20, no. 2 (2014): 203-218.

[5] Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia,(New York: Basic Books, 2001), xiv.

[6] Natale and Balbi, “Media and the Imaginary in History,” 208.

[7] See Rosalind Krauss, “Reinventing the Medium,” Critical Inquiry 25, no. 2 (1999): 289-305.

[8] Tom Gunning, “Re-Newing Old Technologies: Astonishment, Second Nature, and the Uncanny in Technology from the Previous Turn-of-the-Century,” in Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition, eds. Henry Jenkins and David Thorburn (London: The MIT Press, 2004), 39-60.

[9] Natale and Balbi, “Media and the Imaginary,” 211.

[10] Stuart Tannock, “Nostalgia Critique,” Cultural Studies 9, no. 3 (1995): 463.

[11] Nicholas Dames, “Nostalgia and its Disciplines: A Response,” Memory Studies 3, no. 3 (2010): 270.

[12] See for example, Jussi Parikka, What Is Media Archaeology? (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2012), 2; Wolfgang Ernst, Digital Memory and the Archive, edited and with an introduction by Jussi Parikka (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 56; Siegfried Zielinski, Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means (London: The MIT Press, 2006), 10.

[13] Vivian Sobchack, “Afterword: Media Archaeology and Re-Presencing the Past,” in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications, eds. Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 328.

[14] See Dominik Schrey, Analoge Nostalgie in der digitalen Medienkultur (Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos, 2017).

[15] Mikhail M. Bakhtin, “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel: Notes Toward a Historical Poetics,” in The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 147.

[16] Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (London: The MIT Press, 2000).

[17] See Dominik Schrey, “Analogue Nostalgia and the Aesthetics of Digital Remediation,” in Media and Nostalgia: Yearning for the Past, Present, and Future, 27–38.

[18] Henry Jenkins and David Thorburn, “Introduction: Toward an Aesthetics of Transition,” in Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition, 1–18.

[19] Plato, “Phaedrus,” in The Collected Dialogues of Plato, eds. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961), 520.

[20] Mathias Herweg, “Wider die schwarze Kunst? Johannes Trithemius’ unzeitgemäße Eloge auf die Handschriftenkultur,“ in: Daphnis. Zeitschrift für Mittlere Deutsche Literatur und Kultur der Frühen Neuzeit (1400-1750), no. 39, 391–477.

[21] Günther Anders, “The Phantom World of TV,” Dissent, 3, no. 1 (1956): 14–24.

[22] For an early example, see Vivian Sobchack, “The Scene of the Screen. Envisioning Cinematic and Electronic ‘Presence,’” in: Materialities of Communication, eds. Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht and Karl Ludwig Pfeiffer (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994). This essay, originally published in German in 1988, was republished in several slightly revised versions over a course of more than 15 years, gradually attenuating what Sobchack would later self-critically describe as her “dramatic claims” about the nature of the digital. Scott Bukatman, “Vivian Sobchack in Conversation with Scott Bukatman,” in: Journal of e-Media Studies 2, no. 1 (2009).

[23] Eva Horn, “Editor’s Introduction: ‘There Are No Media’,” Grey Room 29, no. 4 (2007): 6–13.

[24] Hartmut Böhme, “Der Wettstreit der Medien im Andenken der Toten,” in Der zweite Blick: Bildgeschichte und Bildreflexion, ed. Hans Belting and Dietmar Kamper (München: Fink, 2000), 28.

[25] Siegfried Kracauer, Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), l.

[26] Jonathan Sterne, “The Death and Life of Digital Audio,” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 31, no. 4 (2006): 338.

[27] Sterne, “Death and Life,” 339.

[28] Ibid.,” 338.

[29] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility: Second Version,” in The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media, eds. Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin (Cambridge: Belknap, 2008), 35.

[30] Erkki Huhtamo, “Dismantling the Fairy Engine: Media Archaeology as Topos Study,” in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, and Implications, eds. Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 27–47.

Dominik Schrey is a lecturer in digital media culture at the University of Passau, Germany. His book Analoge Nostalgie in der digitalen Medienkultur (“Analog Nostalgia in Digital Media Culture”) was published by Kulturverlag Kadmos Berlin in 2017. His current research project, entitled “Alpine Topographies of Loss,” addresses the media ecology of the Earth’s vanishing cryosphere.