Standing with Standing Rock: Media, Mapping, and Survivance

Tuesday, June 5, 2018 at 3:57PM

Tuesday, June 5, 2018 at 3:57PM Janet Walker

[ PDF Version ]

Events at Standing Rock facilitated a resurgence of Indigenous-centered leadership, created new ways to protect the water and the land, and altered the media landscape. [1] Between April 2016 and their forcible eviction in February 2017, Indigenous Water Protectors and non-Indigenous allies gathered to oppose the installation of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and the ravages of fossil fuel extraction through prayer, ceremony, nonviolent direct action, and media activism. The pipeline was designed as an underground conduit to deliver oil from the Bakken shale oil fields in northwest North Dakota to a storage hub near Patoka, Illinois, across lands included in the Horse Creek Treaty (also known as the Fort Laramie Treaty) of 1851 between United States commissioners and representatives of multiple American Indian Nations. Crucially, the pipeline was set to bore under the Missouri River and Lake Oahe, approximately one half-mile north of the Standing Rock reservation. The main resistance camp of this historic assembly was known as Oceti Sakowin or Seven Council Fires—a proper name for peoples of the Great Sioux Nation.[2]

Figure 1. Flags of Native nations and international supporters at Oceti Sakowin, November 2017. Photo by author.

Throughout the resistance, varying opinions were expressed and heard, in keeping with Lakota cultural practices.[3] So it is perhaps unsurprising that when Tribal Chairman Dave Archambault II, anticipating the February rout, thanked people for their efforts and asked everybody to go home, many Water Protectors responded, “We are home.”[4]

As a non-Indigenous supporter and spatial media scholar, I am drawing from trauma and media studies to honor and stand with Standing Rock as the resistance continues and spreads. After the November 2016 national election, I gravitated to Oceti Sakowin, that precious harp-shaped spot between North Dakota Highway 1806 and the Cannonball River (a tributary of the Missouri), with the barricade of Backwater Bridge to the northwest and the Turtle Island Burial Ground to the northeast.

Figure 2. Spaces of resistance. Map of Oceti Sakowin from the original camp website. See #NoDAPL Archive—Standing Rock Water Protectors, www.nodaplarchive.com/ Aerial photograph of the area from Google Maps

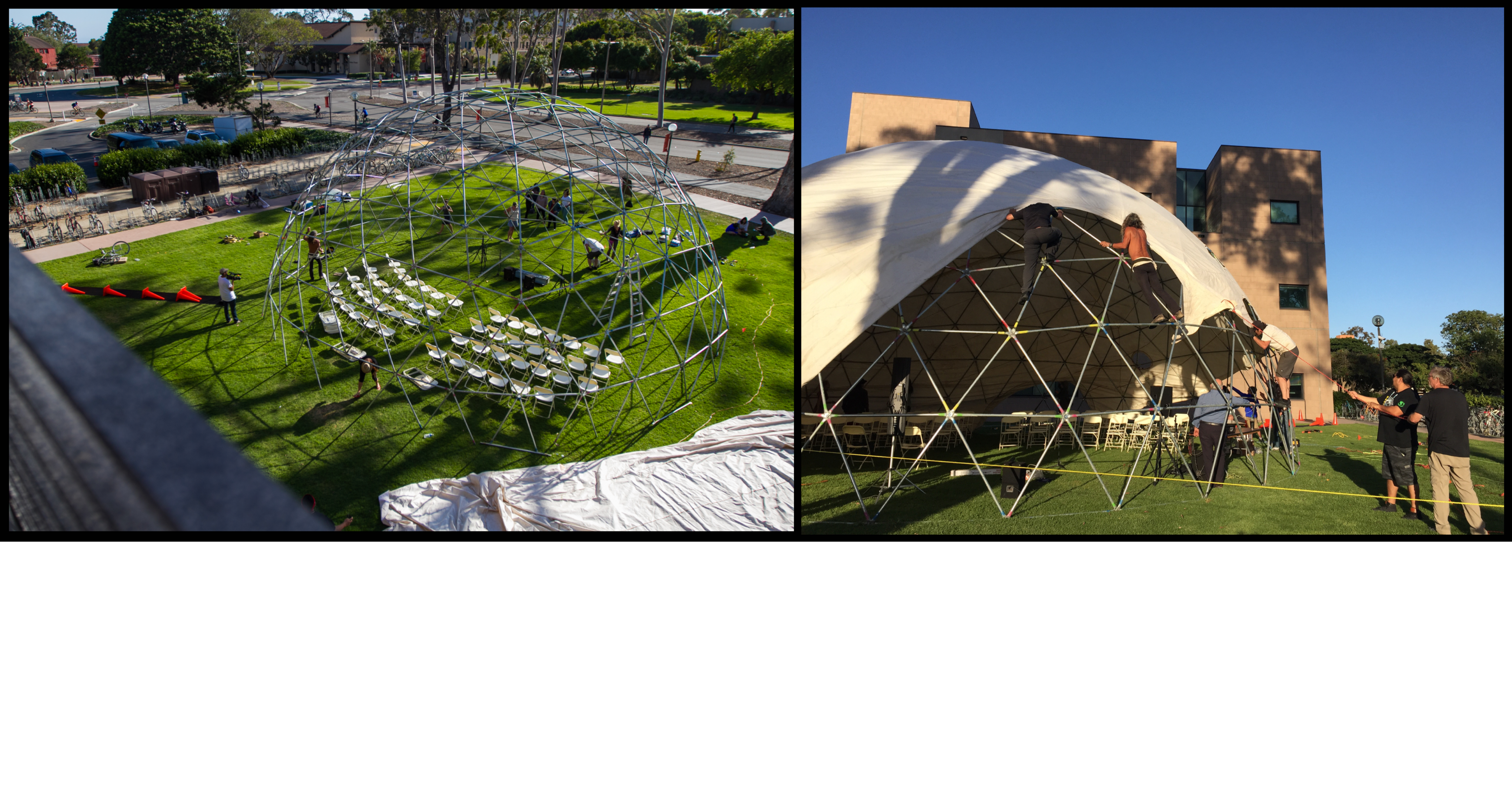

Thousands were present despite winter conditions and a mandatory evacuation order from the governor. Everybody was fed; everybody was sheltered. Solar panels and wind turbines powered the Red Lightning Dome, which housed many of the meetings. Charging stations for small electronic devices lined the sloping sides.

Figure 3. The Red Lightning Dome at Standing Rock. Courtesy of Joshua Tree and the Red Lightning community. See redlightning.org

Figure 4. The Dome in winter. Photos by author.

Green grass sprouted from the thawing ground within the Dome, as if spring had come. In the presence of such infrastructural feats and natural phenomena, all comers had the opportunity to embrace Indigenous-led resistance and to decolonize our minds; to learn how private companies’ ongoing incursions into sovereign land, at Oceti Sakowin and throughout the country, relate to the US’s wretched history of treaties with Indigenous Nations. We were charged to help build a new legacy, to be of use, and to communicate further afield what we were absorbing on site. This article seeks to rise to the occasion by exploring how independent media, mapping, and Mother Earth as mutually constitutive propositions can contribute to a more just and fruitful way of being.

Digital Smoke Signals

During the last two years strangers have looked over our land with spy-glasses and made marks upon it, and we know but little what it means. As we believe that you have no wish to disturb our Possessions, we want to tell you something about this Hopi Land.

Albert Yava, Hopi, to the Washington Chiefs, 1894 .[5]

Independent media-makers worked vigorously to resist the DAPL incursion and to show the world how the unarmed Water Protectors were being surveilled, followed, harassed, arrested, and violently attacked, while mainstream media mostly ignored the story month after month. Unicorn Riot, Indigenous Environmental Network, International Indigenous Youth Council, and Digital Smoke Signals, among other alliances made innovative use of media, including drones, live streaming, web presence, social media, and independent documentary. Myron Dewey, the founder and owner of Digital Smoke Signals, produced drone footage and daily updates from the area and led drone workshops for women and “know your rights” sessions for independent media practitioners.[6] Dewey adopted Facebook Live, which had launched in April 2016, to probe and prod encounters between Water Protectors and extraction enforcers throughout the vicinity of the struggle.

Figure 5. “Live is like having a TV camera in your pocket,” trilled Facebook cofounder Mark Zuckerberg.

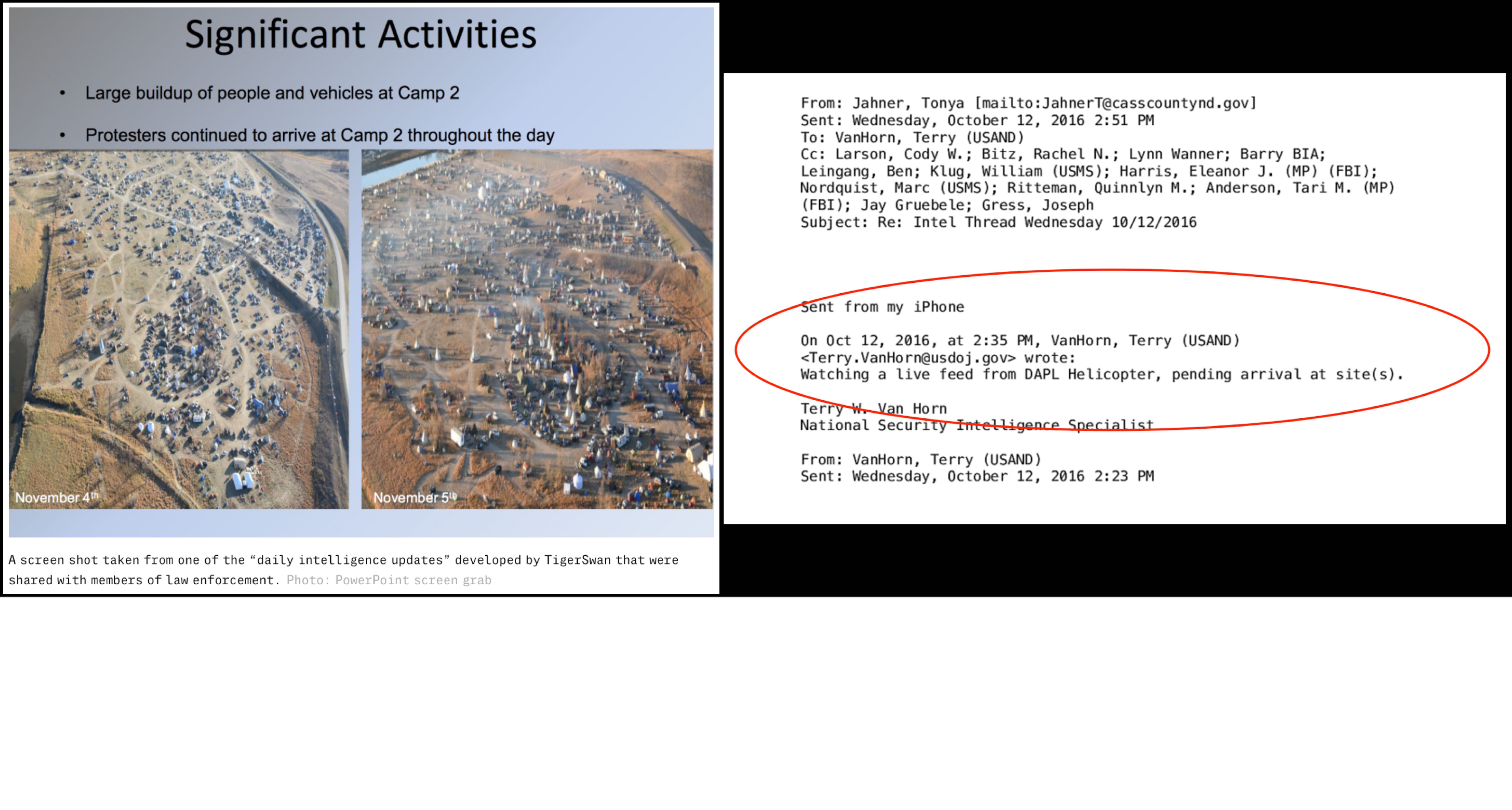

Indeed, various modalities of new media actively formed part of the resistance to the Dakota Pipeline, rather than merely documenting pre-given events. And as always, asserting the right to speak through media required constant struggle. Participants in the resistance report that Facebook turned off Dewey’s live stream of police roughly treating Water Protectors and Unicorn Riot’s live stream of resisters locking onto construction equipment.[7] Also disturbing is the role of TigerSwan, the private security and intelligence firm founded by retired members of the US Army’s elite special mission unit, Delta Force, to provide what the Intercept describes as “military-style counterterrorism measures” during the global war on terror.[8] As was suspected then and later confirmed, TigerSwan was engaged by Dakota Access’s parent company Energy Transfer Partners to enact “sweeping and invasive surveillance of protesters,” whom they characterized as “an ideologically driven insurgency with a strong religious component” and compared to jihadist fighters.[9] TigerSwan’s intelligence reports included a live video feed from a Dakota Access helicopter and photographs from a Phantom 4 drone.

Figure 6. Aerial surveillance and “Intel Thread” by TigerSwan. Source: Intercept (see endnote 8).

Independent media for the resistance persisted. John Bigelow and Paula Antoine ran the Oceti Sakowin camp media team and website out of the Cannonball Recreation Center. They estimated that, at one point, as many as fifteen to twenty journalists were rotating up to the front lines.[10] Dewey directed and appears as a main character in Part III of the omnibus independent feature documentary Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock (dir. Josh Fox, James Spione, and Myron Dewey, US, 2017).[11] This radiant, compelling film arrays with analytical and emotional verve the goals of the Standing Rock resistance: to protect the rivers from contamination for the sake of the seventh generation and the seventeen million people downstream;[12] and to connect the immediate struggle against this oil-filled “black snake” to a history of atrocities perpetrated against Native Americans by US forces and to a future threatened by anthropogenic climate change. Interwoven throughout the film are: prayers, songs, actions, assessments, perorations, expressions of peace and solidarity; aggressions against unarmed Protectors; joyful celebration of the news in December 2016 that the Army Corps had denied the easement and halted the pipeline (temporarily, as it turned out); the curving stripe of the river mirroring a blue sky with white clouds; a prairie encampment lasting through the seasons; the physical and cultural survival of Indigenous peoples and values. Josh Fox states that the film is a “rallying cry.” I stand in awe.

The first words heard in Part III, played over images of the road through a car windshield and the driver’s eyes in the rearview mirror, are Dewey’s: “What I seen happening here at Cannon Ball is what’s happened back on my homeland, my reservation . . . Our water quit running through. And when we got here . . . something that I seen was lacking was filming from an Indigenous perspective. And our story wasn’t being told correctly.” The film proceeds with Dewey enacting several of the mediated encounters with law enforcement and other officials through which he seeks to reestablish the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples and the legal rights of citizens. Reminiscent of the first-person interactive style of Michael Moore’s and Ross McElwee’s documentaries, Dewey’s voice comes from even deeper within this land, this history, this resistance.

Figure 7. A live stream encounter. Still frames from Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock. Courtesy of Myron Dewey.

In one remarkable sequence, Dewey, the artist Prolific the Rapper (Aaron Sean Turgeon), and the driver of the car they are riding in come upon a South Dakota Highway Patrol officer parked at the intersection of State Highway 1806 and County Road 134 (behind the lines, as it were). Realizing that this young man, like most of the officers, is just there on assignment, Dewey and company decide “to strike up a conversation to educate him about Indigenous issues”—and to open the encounter to others via live stream. As Prolific the Rapper comments, the officer seems like a reasonable fellow, his expression and words changing from smug (“There’s a protest up here, that’s probably why you’re up here, isn’t it?” “Oh, yeaah [drawn out skeptically], you just decided to come up here…”) to interested and open. Forearms resting on their respective rolled-down windows (in a stretch of my imagination they’re about to shake hands), the parties discuss. When the officer characterizes the intersection as “the middle of nowhere,” Dewey explains that “we’ve been here for over five hundred years, we’ve been here predating Western contact,” and also that he has often come to the area “working with youth and at-risk youth, teen suicide, sexual abuse . . . we’re doing historical trauma training.” Of course Dewey isn’t “just documenting”; he draws his interlocutor (and his audiences, live and otherwise) into the conversation and into the being of that place. “I’ve heard there are sacred sites,” says the patrol officer. “What makes this road here sacred? I guess I’m kind of curious.” He seems genuinely so. “Ha, how about this?” responds Dewey. Arm out of the window and hand hovering over the ground, he says a prayer in Paiute: “Power and place. Where I pray right now is sacred. It does not have to be designated as sacred by you or anyone else in this country.”

Figure 8. The encounter deepens. Still frames from Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock. Courtesy of Myron Dewey

As Prolific the Rapper tells the highway patrol officer about having been stopped by Morton County officers while filming from a drone, the documentary cuts to footage of that incident. It was an infringement of his constitutional right to film and document, assert Dewey and Prolific the Rapper. But as we learn from a screen graphic, “Within 24 hours of this live video on Facebook [the interaction with the highway patrol officer], a warrant was issued for Prolific’s arrest, a month and a half after the original drone incident.” Whenever a drone flew by at Standing Rock, one hoped to hear “It’s one of ours!”

“Often by treaty but also by force”

Since the founding of this nation, the United States’ relationship with the Indian tribes has been contentious and tragic. America’s expansionist impulse in its formative years led to the removal and relocation of many tribes, often by treaty but also by force.

Cobell v. Norton, 240 F.3d 1081, 1086 (D.C. Cir. 2001)

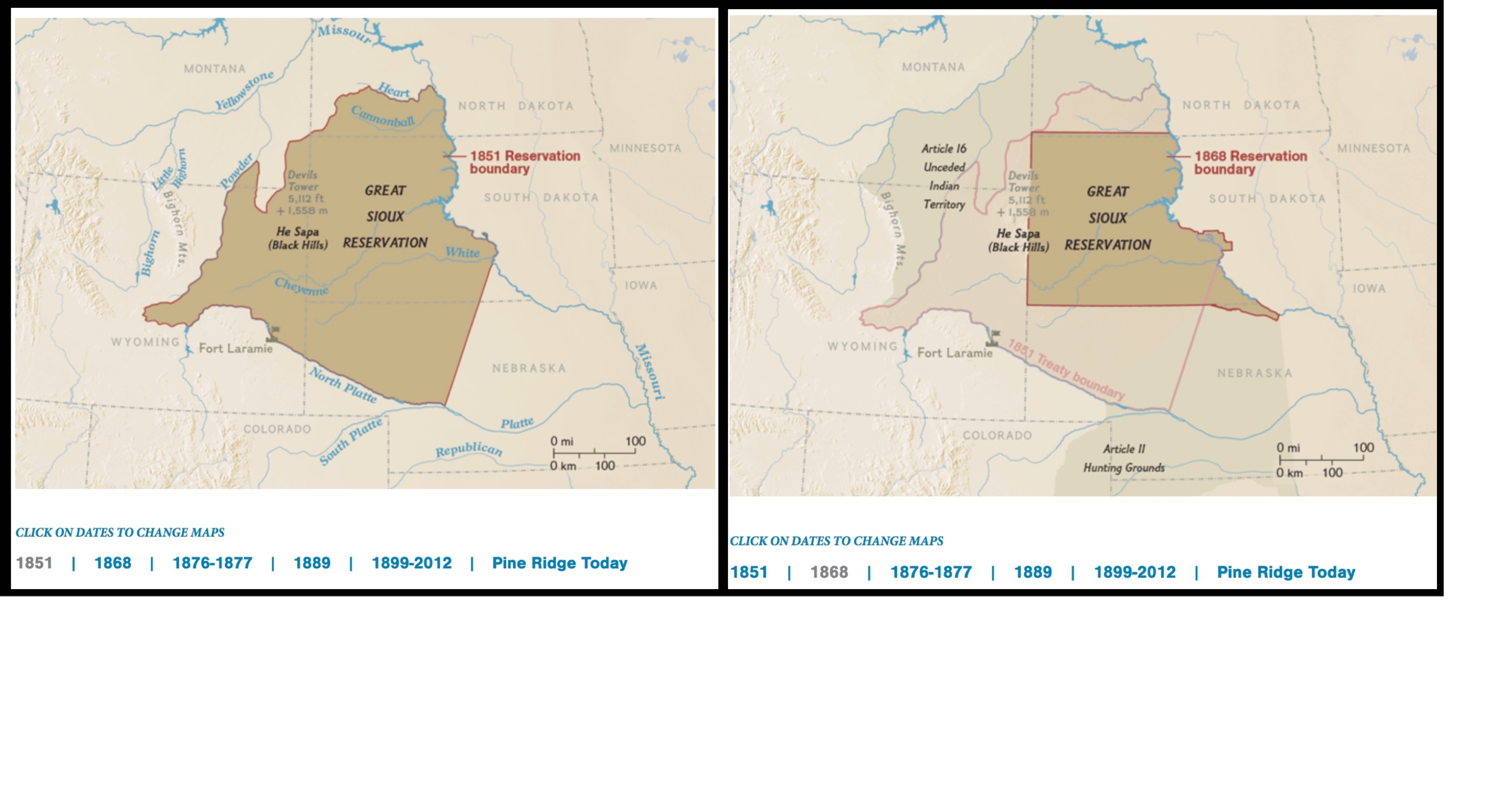

Figure 9. “The Lost Land,” National Geographic(see endnote [13])

The Horse Creek Treaty of 1851 was set between nations—signed by US treaty commissioners and representatives of the Cheyenne, Sioux, Arapaho, Crow, Assiniboine, Mandan, Gros-Ventre, and Arikara Nations, among others—“to maintain good faith and friendship in all their mutual intercourse, and to make an effective and lasting peace.” [14] The Sioux or Dahcotah Nation were provided a territory defined by the area’s riverine geography. [15] The US Government gained the right to establish roads and military posts in the territory and, in consideration of these rights, bound itself “to protect the aforesaid Indian nations against the commission of all depredations by the people of the said United States, after the ratification of this treaty.”[16] The Great Sioux or Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 followed, again according ownership of the Black Hills to the Sioux Nation but reducing the overall area so that the land where Oceti Sakowin would later sit was now outside the boundary.[17]

The word depredations is chilling shorthand for forced displacement; purposeful starvation (US policy called for the decimation of the buffalo); and killing of unarmed Indigenous men, women, and children; acts that were the order of the era before, during, and after the Civil War. Historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz is thorough and unwavering in An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States and other titles. Her historical work tells of Sioux civilians slaughtered by Union Army troops and a mass hanging of prisoners in Minnesota in 1859; [18] the Sand Creek Massacre of Cheyennes and Arapahos in 1864; Custer’s use of “noncombatant hostages” at the Washita River in 1868;[19] the Wounded Knee Massacre of Lakota men, women, and children in 1890;[20] and more. After an Indigenous alliance blocking gold seekers along the Bozeman Trail defeated US Army soldiers attempting to clear the way in December 1866, General Sherman urged Ulysses S. Grant, then commander in chief of the US Army: “We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women, and children.” [21]

This is the lethal environment of settler colonialism within which the peaceful resistance to the DAPL pipeline resolutely held its ground. When asked what she took away from her experience at Standing Rock, Jasilyn Charger, an inspiring cofounder of the encampment, reflected: “I never felt more connected, never felt more empowered. I mean it just activated something inside of me to where I felt like I could live again. . . . No matter who you are, you are native to this land . . . to be able to exist and to be able to say, hey, I’m here . . . that matters.”[22]

Figure 10. Jasilyn Charger speaking at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Source: still image from UCTV video (see endnote 22).Courtesy of Jasilyn Charger

Who belongs to this land? Mapping continues its definitive role, be the map physical, topographic, iconographic, textual, or of another sort. The project to emphasize the representational quality of the map relative to the territory (that is to say, to distinguish the two) is fundamental to the abstractive disciplines including literary theory, semantics, philosophy, history, film and media studies, and physical and human geography).[23] Yet abstractions matter concretely.[24] Critical cartographer J. B. Harley points to the map held by one of the colonists in Benjamin West’s 1771 painting Penn’s Treaty with the Indians: “Maps were more than legal instruments enforcing Indian land treaties, more than strategic documents in colonial wars with the French and more than a tool in the settled areas to divide the farmland or plat the city . . . They exercised power in other ways too . . . Maps often ran ahead of the settled frontier, preceding the axe and the plough.” [25] Maps are constructive and not merely reproductive; they are agential and embed distinct interests.

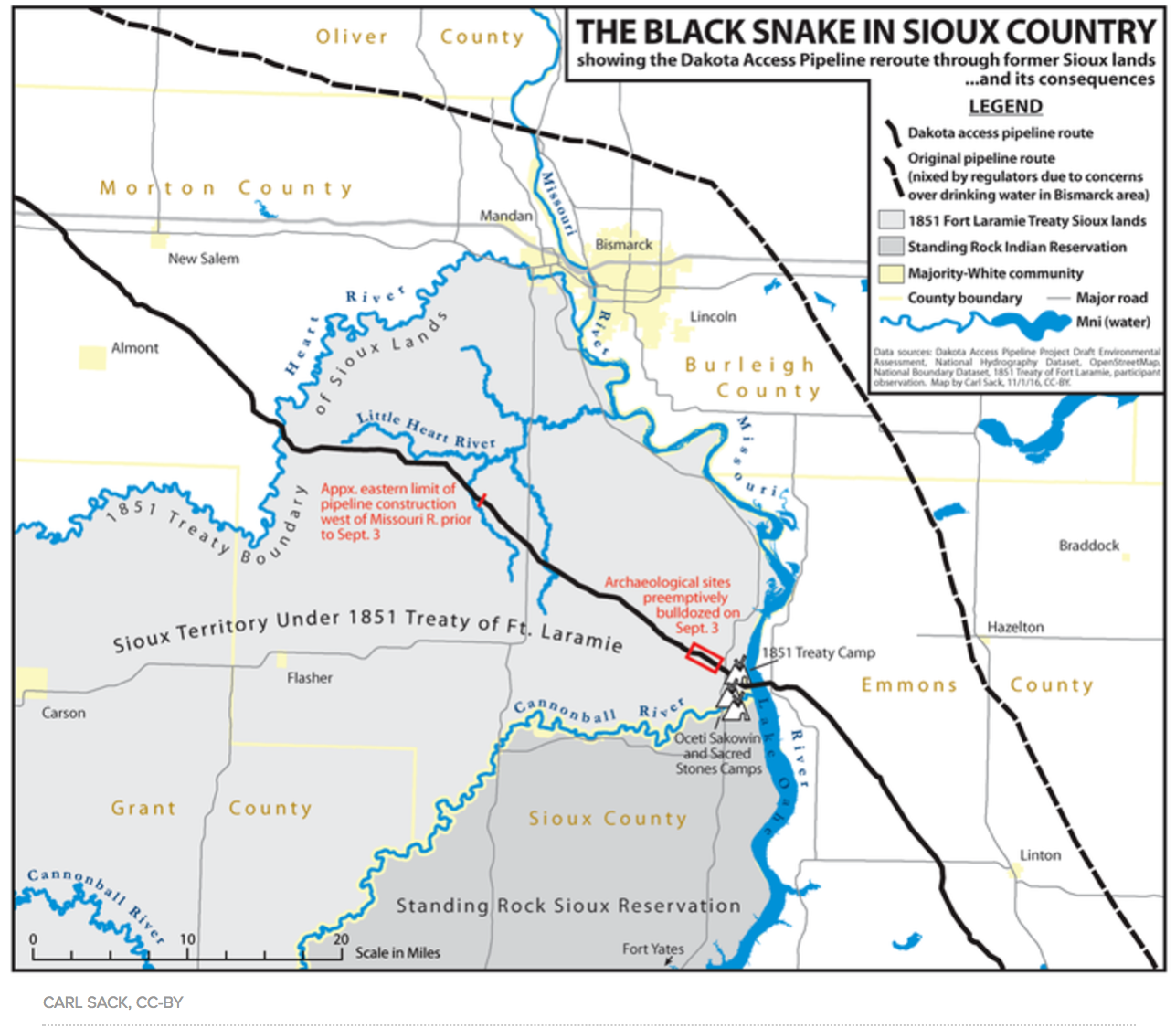

The Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribes continue to seek legal remedies on the basis of cultural, religious, and environmental grounds for harms inflicted by Big Oil on Indigenous people, lands and waters, and planetary well-being. In contrast to DAPL’s spatial imaginary reliant on exclusion, privatization, and corporatization, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe (represented by Earthjustice) has contributed to federal court records a territorial claim that is longstanding and expansive as well as culturally and environmentally rooted. Ninety-nine percent of the pipeline route traverses private land. But because it crosses federally regulated waters in more than one hundred places, a consultative and permitting process is necessary, and can be demanded in federal court. In his Memorandum Opinion of 9 September 2016, United States District Judge James E. Boasberg quoted Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman Archambault: “History connects the dots of our identity, and our identity was all but obliterated. Our land was taken, our language was forbidden . . . What land, language, and identity remains is derived from our cultural and historic sites . . . Even if we do not have access to all such sites, their existence perpetuates the connection. When such a site is destroyed, the connection is lost.” The opinion states, “This Court does not lightly countenance any depredation of lands that hold significance to the Standing Rock Sioux.” [26]

But an area that the Standing Rock Sioux believe to be a burial site was graded by DAPL on 3 September 2016—over the weekend, miles from the active construction site, and apparently to an unusual depth—the day after a declaration was filed in support of the plaintiffs that included detailed maps, metadata, and photographs of the area.[27]

In her subsequent interview with Earthjustice attorney Jan Hasselman, journalist Amy Goodman expressed her outrage, confirming with Hasselman that the court document itself had inadvertently provided “a roadmap to destroy.”[28]

Figure 11. “The Black Snake in Sioux Country”—A #NoDAPL Map. Courtesy of cartographer Carl Sack. See northlandia.wordpress.com/2016/11/01/a-nodapl-map/ (see endnote 28)

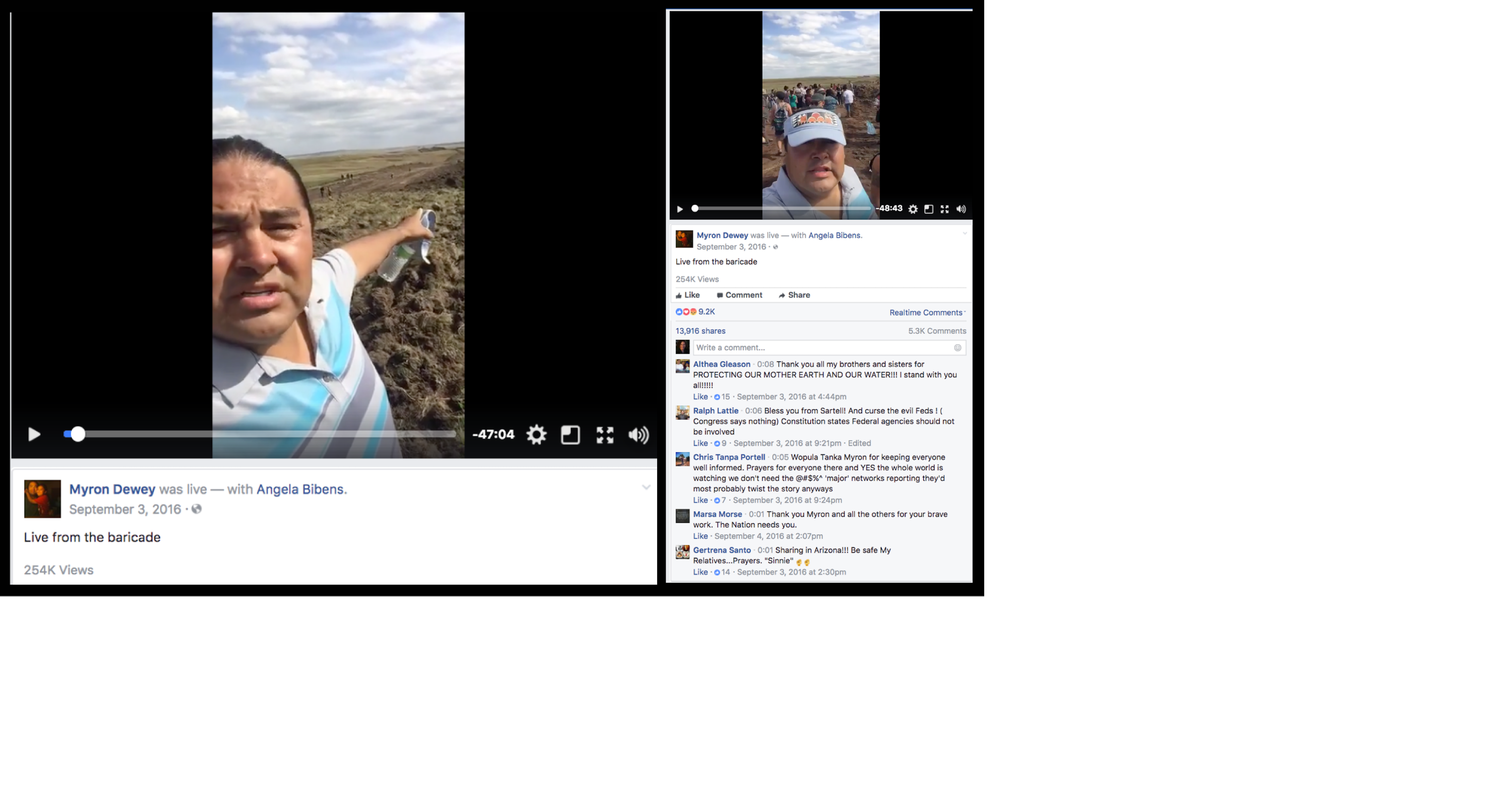

During the grading, tribal members and supporters rushed to the site. Independent media-makers filmed from ground zero, using drones, video, and live stream technology to capture pipeline hirees siccing dogs and Water Protectors under attack and bleary-eyed from pepper spray. This footage and these works constitute a map of another order: an extensive Indigenous cartography beamed live to the world. Twenty video reports from that day are posted to the #NoDAPL Archive.[30] Most originated as live streams with concurrent posts by Digital Smoke Signals, Red Warrior Society of Red Warrior Camp, Linda Black Elk, Jourdan Bennett-Begay, and Democracy Now! among other authors. In a forty-nine-minute live stream, Dewey urged people watching to “share what’s going on, share what’s happening; write comments, you know, send blessings and prayers to our relatives.” This video alone has received 254 thousand views.[31]

Figure 12. Documenting destruction. Still frames from Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock. Courtesy of Myron Dewey.

Figure 13. At the barricades. Still frame from Awake: A Dream From Standing Rock; Screenshot of a Digital Smoke Signals Facebook post. Courtesy of Myron Dewey.

Survivance: A Bridge to Turtle Island

Today we rewrite Thanksgiving, take back thanks-taking, thanks-killing. And we rewrite it as a peaceful prayerful action that shows life.

Words of a young woman in Awake: Standing with Standing Rock

On the day many Americans call Thanksgiving, the Water Protectors crossed a handmade bridge to the sacred burial ground of Turtle Island, then occupied by DAPL forces. Part I of Awake portrays this journey into history, comparing the occupiers to the Seventh Cavalry Regiment. “We defeat fear every day,” states narrator Floris White Bull. “Thanksgiving is actually a massacre,” explains a young woman, “so for our Native American brothers and sisters to be here, to be in a protective stance . . . to say Water Is Life and to show no fear, unarmed, makes their ancestors proud.”

Figure 14. A bridge to Turtle Island. Still frame from Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock. Courtesy of Myron Dewey.

Gerald Vizenor has used the term “survivance” in the context of Native American studies to express “an active sense of presence, the continuance of native stories, not a mere reaction, or a survivable name. Native survivance stories are renunciations of dominance, tragedy and victimry.” [32] What better way to describe the peaceful, prayerful, unarmed, and at times joyful and successful Standing Rock resistance?

The resistance continues throughout the United States at the sites of multiple pipelines. In May 2017, the Dome from Standing Rock was reinstalled on the Visitor Center lawn at the University of California, Santa Barbara, thanks to Johnnie Aseron, Joshua Tree of the Red Lightning community, the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation, and a campus community effort by students, staff, and faculty.[33] It arrived in a heap with the dirt from Standing Rock still on it. UCSB students hosed it clean and several dozen of us erected it in a prominent campus location.

Figure 15. Reinstalling the Red Lightning Dome from Standing Rock at UC Santa Barbara. Photos courtesy of Brendan Byrne.

Joye Braun, among the first members of the Standing Rock resistance to make camp, live streamed over Facebook that she never thought she would sit once more inside “our Oceti Sakowin Dome.” Others can be heard calling out from offscreen: “Mni Wiconi! Mni Wiconi! We’re going to do it again!” “No, it won’t be the last time,” affirms Braun. “First of many, we’ll set it up lots of other places!”[34] Spread the story and history of survivance. Water is life.

Dedication

With enormous gratitude I dedicate this article to the Water Protectors who joined us at the University of California, Santa Barbara in May 2017 for four days of events that comprised “Water Is Life: Standing with Standing Rock”: Paula Antoine, Johnnie Aseron, John Bigelow, Joye Braun, Jasilyn Charger, Myron Dewey, Terrell Iron Shell, Mark Tilsen. I dedicate it also to Mia Lopez, Michael Cordero, and the Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation as traditional custodians of the land where UCSB sits and as “Water Is Life” co-hosts. Many thanks to members of UCSB’s American Indian Student Association who participated enthusiastically in this initiative and to the Academic Council of the American Indian and Indigenous Collective; to the Carsey-Wolf Center and staff partner Paula Firth; and to Todd Darling, Claudio Fogu, and Margaret McMurtrey, inspired and inspiring colleagues with whom it was my honor and pleasure to co-organize “Water Is Life: Standing with Standing Rock.”

www.carseywolf.ucsb.edu/research/democracy/water-life-standing-standing-rock/

Notes

[1] Independent filmmaker Todd Darling (Media Bridge Dispatch), University of California, Santa Barbara Professor Claudio Fogu, and I composed a version of this first sentence as we began the project that became “Water Is Life: Standing with Standing Rock.” I would also like to thank Claudio Fogu for his warm encouragement and insights as I began to write this article.

[2] See “Stand with Standing Rock: Camp Information,” standwithstandingrock.net/oceti-sakowin/ (accessed 21 January 2018). “Standing Rock” became the popular designation of the place and occasion of this resistance and of the multiple encampments on treaty land near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. I will use the term as such from time to time in this article.

[3] At the University of California, Santa Barbara, Johnnie Aseron emphasized the importance of listening and making time for each person wishing to contribute to the conversation. He did so during a presentation and discussion along the lines of that which he regularly facilitated at Oceti Sakowin to help newcomers to the camp—especially non-Native allies—learn about the seven Lakota values and integrate into the cultural protocol of the Standing Rock First Nations community. Aseron, Executive Director of the Inter-National Initiative for Transformative Collaboration (INITC), served as the Wellness Initiative and Interfaith Coordinator for the duration of Oceti Sakowin Camp. See “Oceti Sakowin Camp Protocol: 7 Lakota Values,” Standing Rock Solidarity Network, (accessed 1 September 2017).

[4] Jeremiah Jones and M. David, “Standing Rock Sioux Leader Says Protesters Should ‘Go Home’ For Now—Tens of Thousands Stream Into Camp Responding ‘We Are Home,’” Counter Current News, 8 December 2016, countercurrentnews.info/2016/12/standing-rock-sioux-leader-says-protesters-go-home-now-tens-thousands-stream-camp-responding-home/.

[5] Quoted in Peter Nabokov, ed., Native American Testimony: A Chronicle of Indian-White Relations from Prophecy to the Present, 1492–2000, revised edition (New York: Penguin Books, 1999; 1978), 249

[6] Myron Dewey is Newe-Numah/Paiute-Shoshone from the Walker River Paiute Tribe, Agui Diccutta Band (Trout Eaters), and Temoke Shoshone. He is a professor, journalist, filmmaker/editor, digital storyteller, historical trauma trainer, drone operator, and founder and owner of Digital Smoke Signals. See Digital Smoke Signals www.digitalsmokesignals.com/ (accessed 1 September 2017) and Digital Smoke Signals’ Facebook page, www.facebook.com/DigitalSmokeSignals/ (accessed 1 September 2017). To watch a panel discussion including Dewey on UCTV, see Carsey-Wolf Center, Water Is Life: Standing with Standing Rock—Media, www.uctv.tv/shows/Water-Is-Life-Standing-with-Standing-Rock-Media-32569 (accessed 18 January 2018).E

[7] Todd Darling informed me of these alleged actions by Facebook. See Christopher S. Pineo, “Facebook Blocking Red Warrior Posts?,” Native News Online.net, 1 October 2016, nativenewsonline.net/currents/facebook-blocking-red-warrior-posts/ (accessed 26 January 2018).

[8] Alleen Brown, Will Parrish, and Alice Speri, “Leaked Documents Reveal Counterterrorism Tactics Used at Standing Rock to ‘Defeat Pipeline Insurgencies,’” Intercept, 27 May 2017, theintercept.com/2017/05/27/leaked-documents-reveal-security-firms-counterterrorism-tactics-at-standing-rock-to-defeat-pipeline-insurgencies/. See also “About,” TigerSwan, www.tigerswan.com/about-tigerswan/ (accessed 1 September 2017). For the group email thread depicted in figure 5b see “Intel Group Email Thread,” Intercept, 27 May 2017, theintercept.com/document/2017/05/27/intel-group-email-thread/

[9] Brown, Parrish, and Speri, “Leaked Documents.”

[10] To watch a panel discussion featuring Bigelow and Antoine on UCTV, see Carsey-Wolf Center, Water Is Life: Standing with Standing Rock—Media, www.uctv.tv/shows/Water-Is-Life-Standing-with-Standing-Rock-Media-32569 (accessed 18 January 2018).

[11] The film premiered on Earth Day 2017 at the Tribeca Film Festival and has been playing in theaters and community centers around the world. It is available to stream online at awakethefilm.org/.

[12] The concept of the “seventh generation,” often said to have originated with the Iroquois but widely adopted by Native American cultures, is the idea that humans should make decisions in light of and for the benefit of generations to come. See Oran Lyons, “An Iroquois Perspective,” in American Indian Environments: Ecological Issues in Native American History, ed. Christopher Vecsey and Robert W. Venables (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1980). See also Vine Deloria, Jr., “American Indians and Moral Community (1988),” in For This Land: Writings on Religion in America (New York: Routledge, 1999).

[13] This interactive map can be found at “The Lost Land,” National Geographic, ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2012/08/pine-ridge/reservation-map (accessed 1 September 2017).

[14] Article 1 in “Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 (Horse Creek Treaty),” National Park Service, www.nps.gov/scbl/planyourvisit/upload/Horse-Creek-Treaty.pdf(accessed 1 September 2017).

[15] See “Fort Laramie Treaty,” Article 5: “The aforesaid Indian nations do hereby recognize and acknowledge the following tracts of country, included within the metes and boundaries hereinafter designated, as their respective territories, viz: commencing the mouth of the White Earth River, on the Missouri River: thence in a southwesterly direction to the forks of the Platte River: thence up the north fork of the Platte River to a point known as the Red Bute, or where the road leaves the river; thence along the range of mountains known as the Black Hills, to the head-waters of Heart River; thence down Heart River to its mouth; and thence down the Missouri River to the place of beginning.” In Charles J. Kappler, ed., Laws (Compiled to March 4, 1927), vol. 4 of Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1929), dc.library.okstate.edu/digital/collection/kapplers/id/26435/rec/1 (accessed 18 January 2018).

[16] Article 3, “Fort Laramie Treaty.”

[17] These and other such treaties, 371 during the first hundred years of the United States’ existence, were the context for the Indigenous loss of approximately two million square miles of land either through the treaty agreements themselves or through their breaching. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2014), 142. See also “Standing Rock Sioux Tribe—History,” www.standingrock.org/content/history (accessed 21 January 2018).

[18] Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History, 136.

[19] Richard Allan Fox, Jr., Archaeology, History and Custer’s Last Battle: Little Big Horn Reexamined (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), 297.

[20] Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History, 154–57.

[21] Sherman to Herbert A. Preston, 17 April 1873, quoted in John F. Marszalek, Sherman: A Soldier’s Passion for Order (New York: Free Press, 1992). Also quoted in Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History, 145.

[22] See Jasilyn Charger’s discussion on the panel “Water Is Life: Standing with Standing Rock—Protecting the Land and the Water,” held at the University of California, Santa Barbara, on 19 May 2017. www.uctv.tv/shows/Water-Is-Life-Standing-with-Standing-Rock-Protecting-the-Land-and-the-Water-32571 (accessed 18 January 2018).

[23] Following Alfred Korzybski, we know that the map is not the territory and the word is not the thing. Korzybski, Science and Sanity—An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics (Institute of General Semantics, 1994; Alfred Korzybski, 1933), 498.

[24] As Korzybski himself discussed.

[25] J. B. Harley, The New Nature of Maps: Essays in the History of Cartography, ed. Paul Laxton (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2001), 141, 144.

[26] Decl. of Dave Archambault, II filed in Support of Motion for Preliminary Injunction 6, 15, Standing Rock Sioux Tribe v. US Army Corps of Engineers, 205 F. Supp. 3d 4 (D.D.C. 2016).

[27] I have been able to consult the more than fifty pages of cartographic information that the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe filed in support of its Motion for Preliminary Injunction, but decided not to reproduce any of it here because of what happened on 3 September 2016. See Supp. Decl. of Tim Mentz, Sr. in Support of Motion for Preliminary Injunction, Exhibits 1–4, Standing Rock Sioux Tribe v. US Army Corps of Engineers, 205 F. Supp. 3d 4 (D.D.C. 2016).

[28] “Did the Dakota Access Pipeline Company Deliberately Destroy Sacred Sioux Burial Sites?” Democracy Now!, 6 September 2016, www.democracynow.org/2016/9/6/did_the_dakota_access_pipeline_comp. An excerpt from Amy Goodman’s interview with Hasselman appears in Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock. The widely circulated “The Black Snake in Sioux Country”—A #NoDAPL Map created by cartographer Carl Sack shows both an initial pipeline route and the pipeline route through treaty territory. It also includes an area labeled “Archaeological sites preemptively bulldozed on Sept. 3.” The map is a superb example of what Sack terms “resistance mapping.” northlandia.wordpress.com/2016/11/01/a-nodapl-map/ (accessed 19 January 2018).

[29] Some of this footage is incorporated into Part III of Awake: A Dream from Standing Rock.

[30] See “Frontlines Water Protector Actions and Prayers, Frontlines Water Protector Witness Accounts, Frontlines Water Protector Video Documentation, and Important Standing Rock Legal Matters,” #NoDAPL Archive, www.nodaplarchive.com/sept-daily.html (accessed September 2017).

[31] The link to Dewey’s video posted to #NoDAPL Archive (www.nodaplarchive.com/sept-daily.html) directs viewers to his Facebook post at www.facebook.com/myron.dewey1?hc_ref=ARQsBWhjbYYaHZLabZwlfQbRgfMOzWyfQ9b-EYhrBU7Gjs01LoqeH7P68y_vH5OE4bk (accessed 18 January 2018).

[32] Gerald Vizenor, Manifest Manners: Narratives on Postindian Survivance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), vii.

[33] In bringing the Dome to the University of California, Santa Barbara, we, the co-organizers of “Water Is Life: Standing with Standing Rock,” were supported by three dozen individuals or campus units including Chancellor Henry Yang, Executive Vice Chancellor David Marshall, Vice Chancellor for Administrative Services Marc Fisher, Dean John Majewski, Carsey-Wolf Center Director Patrice Petro and Associate Director Emily Zinn, Interdisciplinary Humanities Center Director Susan Derwin, and dozens of departments, offices, and individuals. For the construction and programming of the Dome, we are grateful to UCSB students from the American Indian Student Association including Jessica Foster, Manny Luna, graduate student Keri Bradford, and UCSB alumna Jessica Alvarez; to Brendan Byrne, who photographed the process; and to all who lent a hand. We also thank UCSB staff members who helped make the Dome a digital hub, including Jim Gallagher, Todd Gillespie, Jonathan Cook, Brad Hughes, Jim Morrison, and Bryan Sandoval. We thank Mia Lopez and members of the Chumash Coastal Band who blessed the space, Professors John Foran and Candace Waid who held class meetings there, and those who offered additional blessings and music. Joshua Tree, Simone Schulz, LeRoy West, Jacqstar Davies, Blackhorse Shasta, and Zenergy of the Red Lightning community brought the Dome to UCSB and guided its reinstallation and abidance on our campus. Deep thanks to them and the entire community for sharing their Dome with us. See redlightning.org.

[34] See “Oceti dome,” video, Joye Braun’s Facebook page, www.facebook.com/joye.braun/videos/10155945183524057/?hc_ref=ARQ_mGIiRc3Cay3Qs2cztAGaetOP-hNtm0M-Ia325wo98RIFvmrfVaAN2Bn_5F6EuTA&pnref=story (accessed 1 September 2017).

Janet Walker (PhD, 1987, UCLA) is Professor of Film and Media Studies and an affiliated faculty member of the Department of Feminist Studies and the Comparative Literature Program at UC Santa Barbara. With research specializations including documentary film and media, trauma and memory studies, and media and environment, Walker is author or editor of six books and numerous published essays. She is the recipient of a Mellon Sawyer Seminar grant for the project "Energy Justice in Global Perspective" (2017-2019) with UCSB Professors Javiera Barandiaran, Mona Damluji, Stephan Miescher, and David Pellow; and of a short-term residency grant (2017) for travel to the Rachel Carson Center in Munich, Germany to work with colleagues on the development of the journal Media + Environment. Her current project is a book on media, mapping, and environment.

Reader Comments