S-Town, Shit World: A Queer Soundscape for the Anthropocene

Thursday, June 7, 2018 at 3:59PM

Thursday, June 7, 2018 at 3:59PM Christina Belcher

[ PDF Version ]

Before committing suicide in 2015, John B. McLemore—the boisterous, brilliant, and utterly miserable polymath at the center of the sensational 2017 podcast S-Town—was a queer stuck in rural Alabama. Queers, not stuck but rather thriving in Alabama and other “shit” places across the US, were the subject of a theoretical trend in queer studies nearly a decade ago. In 2010, Scott Herring’s groundbreaking Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism challenged the field to imagine queer rurality beyond the recurring cultural nightmare of queers stuck in place, miserable, trying to survive among a not-so-silent majority of backward rednecks and evangelical Christians eager to deny them basic human dignity (much less civil rights). Queer cultural historians such as Herring assembled archives of queer rurality that drew attention to the artists, writers, and activists who used “rural stylistics” to critique what Jack Halberstam termed the “metronormativity” of gay and lesbian communities.[1]

According to Halberstam, metronormativity is the spatial narrative that maps onto the coming-out narrative. We imagine that gays and lesbians escape secrecy, persecution, and isolation in small towns and rural areas, finding community, health, and hospitality when they arrive, newly out and proud, in American cities such as New York or San Francisco. [2] Not only does this metronormative narrative silence the forms of violence done to queers—particularly low-income queers, sex workers, disabled queers, and queers of color—in the supposed bastions of equality otherwise known as cities, but it also produces the backward “country homosexual” as a devalued and unenlightened segment of the population, out of touch with queer life. This depiction could very well apply to John B. McLemore, who did not even own a television to watch Brokeback Mountain (dir. Ang Lee, US) in 2005, though he did eventually read Annie Proulx’s short story on which the film was based, referring to it as “the grief manual.”Rather than mourning McLemore's suicide as yet another tragic, queer life unlived, this essay considers the pain, beauty, and complexity of his relationship to the earth, both before he died and in his afterlife, when his voice was reportedly downloaded over forty million times.[3] My hope is that this consideration will complicate the outraged yet apathetic responses to climate change that mark most progressive hand-wringing over the issue, as McLemore's response to harmful carbon emissions, negligent resource extraction, and human apathy in the face of these practices demonstrates a queer relationship to our slow, collective destruction.

In their introduction to Queer Ecologies, Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson ask a series of questions about the ways that queer theory might speak to ecology and vice versa. They ask, “[How] might a clearer attention to issues of nature and environment—as discourse, as space, as ideal, as practice, as relationship, as potential—inform and enrich queer theory, lgbtq politics, and research into sexuality and society?” [4] McLemore provides a way of approaching this question. When asked what he believed McLemore would think of S-Town, podcast host and producer Brian Reed speculated, “He would wish there was more discussion of climate change.” [5] Reed insists that McLemore would have bemoaned climate change, not anti-gay bigotry, had he lived to hear the story of his life in podcast form. Attention to McLemore’s obsession with environmental disaster and his profound love for the earth can teach queer theory about desire and despair on a scale grander than the bedroom, the leather bar, or the classroom. McLemore’s anthropocenic love affair with the planet in decline is a different kind of queer rural love than those that have been noted in studies of rural queer life.

And yet McLemore contributes to those rural archives as well. By resisting Brokeback Mountain—the “grief manual” on rural gay romance—McLemore practices his own form of what Scott Herring terms “rural stylistics,” demonstrating a “[refusal] to comply with the iconic geographics of compulsory U.S. metronormativity,” which “antagonizes the phantasmatic urban/rural divide.”[6]

John’s refusal to comply with an interest in Brokeback Mountain, among other acceptable gay male lifestyle choices such as a neat manner of dress, also antagonized his would-be lover Olin Long. The centerpiece of S-Town’s penultimate episode, Olin describes his anger at John’s refusal to care about Brokeback Mountain, driving him to beat his frustration into the damp night ground of his backyard. “I wanted him to relate to it,” Olin tells Reed, in his recollection of the complicated friendship between the two men. This requirement that McLemore relate to Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist, the tragic cowboys who never truly find their way out of the closet and into a properly codified gay relationship, is a requirement of metronormativity: denounce the country and participate in the cultural narratives of queer urbanity. Not participating in the compulsory narrative of metronormativity—and not adequately mourning his inability or unwillingness to make the journey toward self-acceptance and love that even Ennis Del Mar makes (albeit too late) in “the grief manual”—John B. McLemore’s queer life lived in Alabama demonstrates a queer rurality that exceeds metronormative attempts to discipline and contain it. McLemore was more than a queer stuck in Alabama, and his life should not be reduced to that narrative. But he was a queer stuck in Alabama nonetheless. He bemoaned and yet rationalized his decision to stay. Because what’s a shit town in a shit world, anyway?

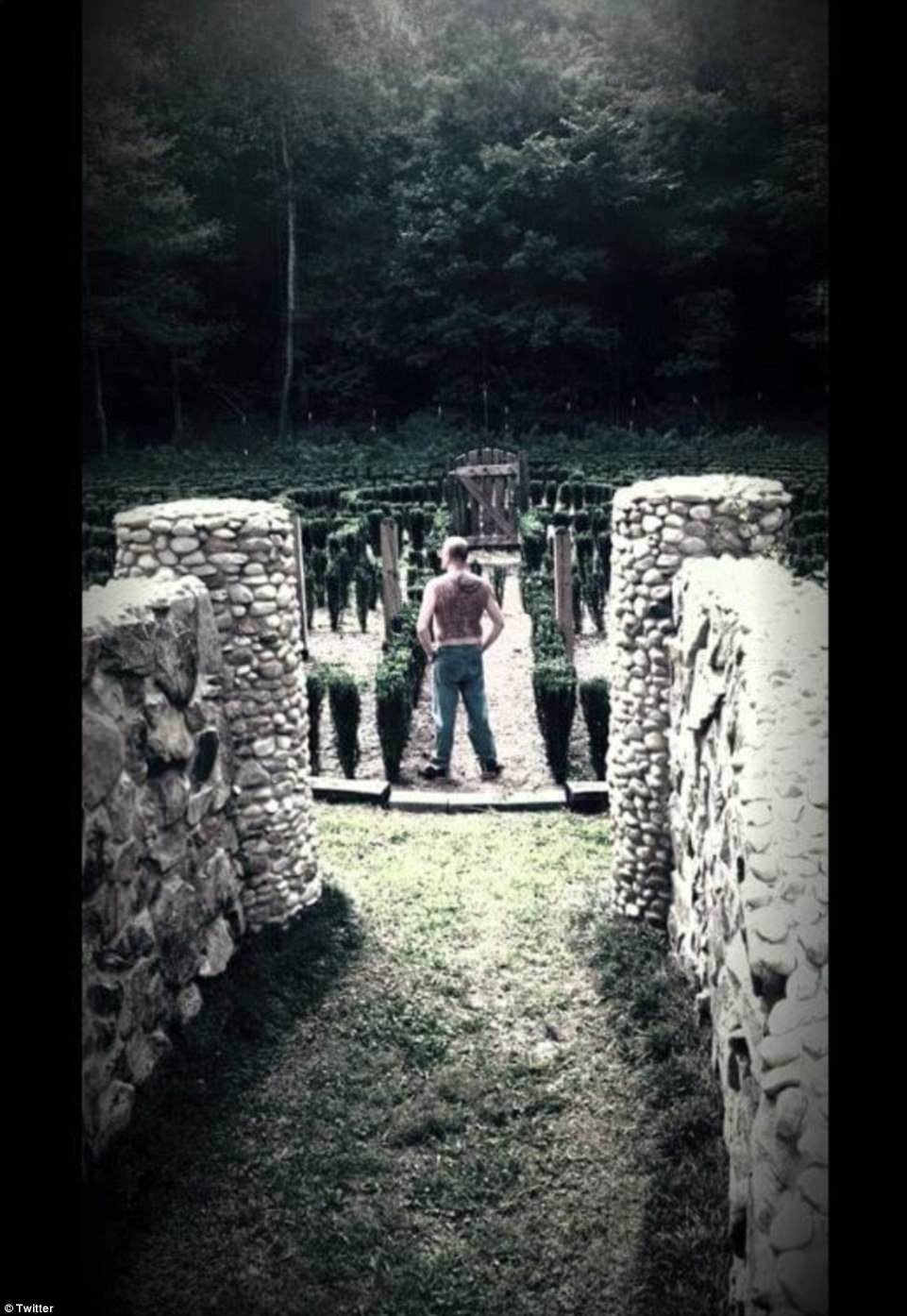

[Figure 1 - McLemore standing at the entrance to his hedge maze, Woodstock, Alabama.[

A middle-aged, self-described “semi-homosexual” with a shock of bright red hair and a heavily-tattooed torso, John B. McLemore stands at the entrance to the intricate hedge maze on his sprawling, ancestral property in Woodstock, Alabama. With his hands placed firmly on his hips, John surveys his maze, its adjustable gates allowing for sixty-four possible solutions, and offers, “You know, I designed this thing myself, so it was designed by a mad man.” The mad man and journalist Brian Reed wind through the hedge maze, hitting dead end after dead end, caught in a predicament of John’s own making. Sixty-four possible solutions, and McLemore stands baffled, with Reed wondering: has John intentionally gotten them lost, for literary flair, for dramatic effect? John curses, and then exclaims, “Actually lost in our own maze! Isn’t that exciting?” Sixty-four possible solutions, but “It is possible to set it up where there is no solution, and I accidentally did that.” Pacing the maze, searching for the way out, John B. McLemore eschews all possible solutions.

The world is a shit town. By comparison, John’s hedge maze, which Reed tells listeners will be destroyed after its purchase by a man invested in the property’s yield of timber, is a beautiful problem. Unlike those problems that ultimately drove McLemore to suicide, the hedge maze would be solved, over and over again. The befuddlement, the meandering: these are the elements that define the murder mystery and treasure hunt that ultimately give way to character study in S-Town, produced by the creative team behind This American Life and Serial. But beyond a portrait of man and town, S-Town provides listeners with what John B. McLemore aptly calls “a clusterfuck of sorrow.”

S-Town documents the collapse both of self and of scale. McLemore’s loose categorization of the world’s injustices into a “clusterfuck of sorrow” defines the queer relationality that he documents and experiences between human and nonhuman—indeed, between the human and the planetary. Of climate change, McLemore remarks, “The whole goddamned Arctic summer sea ice is going to be gone by 2017; we are fixin’ to have heat waves in Siberia this year.” Likewise, he describes a skirmish among self-proclaimed “white trash” that resulted in bloodshed, partygoers scattering as police approached to evaluate the injured parties: “Hiding in the woods: that’s the Bibb County equivalent of having your afternoon tea in London.” McLemore categorizes this cowardice alongside the events of Tyler Goodson’s life, whose struggles with law enforcement, attaining steady employment, and raising his daughters are a central focus of the podcast. “Tyler almost embodies everything I hate about this shit town in one convenient package.” And finally, in his attempts to adequately bemoan “Shit Town,” McLemore returns over and over again to the number of convicted sex offenders in Bibb County: Vance, Alabama “is now one child molester for every 192 citizens!”

Typhoon Nock-ten in the Philippines, a tsunami in Sri Lanka, floods in Pakistan, Chernobyl, the recruitment efforts of the KKK, the diminishment of affordable fossil fuels: to John, there is no distinction between the local, the global, and the corporeal. All of these events are collapsed into a single “clusterfuck of sorrow” that he is eager to disclose to anyone who will listen. This impulse toward exposure leads McLemore to contact Reed and invite him to Woodstock, Alabama, also known as “Shit Town,” to shake the rest of us awake from our collective shrug of shoulders.

While Reed does his best to follow John's queer collapse of scale, he does not ultimately seem to understand how melting glaciers, fleeing the scene of a crime, Tyler Goodson, the sexual abuse of children, you, and I are intimately connected in John's queer ecology. No matter how long he listens to and records the complaints, philosophies, and racial epithets reverberating against the walls of Black Sheep Ink—a haven for “criminals, misfits, and hillbillies”—Reed separates “their tales of getting jerked around by cops and judges and clerks and bosses” from what plagues the rest of us and what plagued John B. McLemore until the night of his last breath. They are included as background to John's exceptionality. They throw his worries about the planet into sharp relief: the micro and the macro, the banal and the extraordinary. Reed separates himself from those Alabama “black sheep” as well. He recalls how he increased his social media privacy settings, fearful that these men who nonchalantly toss around racial slurs will discover that he left his African American wife at home in New York to record them in the tattoo shop, where he took whiskey shots and smoked weed, not to feel a drug-induced escape like the others, but to avoid being suspected as a “narc.”

[Figure 2 - Bearded and outfitted in Carhartt and flannel, Reed strikes a rural pose, with microphone, in Bibb County, Alabama.]

Listening to John’s queer collapse of distinction, scale, and gravity—the interconnections between miseries we typically categorize as large or small—a question emerges: what do we make of a man who feels the world’s sorrows as his own? What do we make of a man who spends his days poring over the details of climate change, the destruction of land and sea, and who spends his nights destroying his own body, begging for a “pain fix” to make the day’s findings fade toward quiet? While Reed gives voice to John’s distress over the lack of outrage aimed at the “clusterfuck of sorrow”—human and environmental—that dooms us all, Serial Productions answers this question in a manner ill-suited to McLemore's queer ecology. The podcast inaccurately presents S-Town as a story of local scale: “a man named John . . . despises his Alabama town and decides to do something about it.” That “something” is not ultimately the demand for criminal justice in a covered-up murder, or even the salvation of local outcast and petty criminal Tyler Goodson, both of which are presented as the story's raison d'être at different narrative junctures. Neither is that "something" the expected queer activist commitment to the slow march of progress, enabling other queers with "a little sugar in [their] tank" to be out in the South—an outcome a number of LGBT critics have claimed for the series.[7] Rather, John B. McLemore “does something” about our collective misfortune by committing suicide, by drinking potassium cyanide.

The relationship between man and world, citizen and town, figures John B. McLemore as a queer sort of melancholic. His attachment to the world, and all the pain and loss the attachment entails, renders him a martyr, for shouldn’t we all lack the capacity to mourn that which we have undergone and continue to undergo? His capacity for and openness to the pain of the world that surrounds him—from the residents of Shit Town to the inhabitants of Earth—demonstrates a queer relationality to our world and an overwhelming vulnerability to our collective ruin.[8]

Toward the end of the seven-episode podcast, after accepting that we are not going to solve a murder mystery, nor find a pot of gold, listeners discover that John likely suffered from mad hatter disease caused by mercury poisoning: mood swings, nervousness, irritability, emotional changes, insomnia, headache, abnormal sensations, muscle twitching, tremors. A lifelong horologist and gifted clock restorer who practiced the dangerous method of fire-gilding, John likely coated his lungs with elemental mercury. To preserve and to restore, John expired. At least John left a beautiful way to count the “tedious and brief” days.

[Figure 3 - McLemore’s former professor, Tom Moore, displays the sundial John built for him]

Many of us are being poisoned in this shit world, in shit towns across America. Lead seepage into drinking water has caused a state of emergency in Flint, Michigan. A high level of lead in the blood, particularly of pregnant women and children, causes learning disabilities and behavioral problems. In West Virginia, three hundred thousand residents of the state’s largest city couldn’t drink or bathe in their tap water for months. Ten thousand gallons of “crude-MCHM,” a chemical with effects largely unknown, spilled into the water supply from a crumbling storage tank.[9] The chemical is used to wash coal. In March 2017, the Trump administration announced a sweeping executive order that effectively demolished Obama-era policies on climate change. By repealing climate regulations such as emissions restrictions for coal-fired power plants, Trump has supposedly unshackled fossil fuels industries. Coal industry jobs can return to the country. Rural America, we are told, is ecstatic. Surrounded by coal industry workers, Mr. Trump signed the executive order he promised his rural voters during his campaign. The smiling men appear ready to get back to work, to “make America great again.” My mother, a factory laborer in West Virgina, recounts a coworker’s excitement the day after this deregulation was announced. With those long, nasal vowels that connect the accents of hillbillies from West Virginia to Alabama, her coworker exclaimed, “They’re bringin’ back the coal jobs, man! I’m gettin’ out of this plant.” Another shit town in a shit world. It’s almost a blessing that John B. McLemore didn’t live to see this.

[Figure 4 - Trump, with EPA Director Scott Pruitt and a group of coal industry workers, signing executive order, March 2017]

During a night of whiskey shots in his workshop, McLemore lifts his shirt, flashing Reed his “expression of hopelessness,” as John describes the practice of tattooing. “That’s your entire chest, John! And nipple piercings!” After John’s death, Tyler Goodson explains the role that piercing and tattooing played in the final years of John’s life: “We called it Church.” John began asking Tyler to tattoo over his existing tattoos, again and again, and to pierce his nipples, as Tyler describes, just for the “pain fix.” In regards to “Church,” Reed describes what it was like to be inside John’s mind:

You know what it’s like to get a song stuck in your head, where it’s just playing over and over and you just can’t get it out of there, even if it’s a terrible song? That’s what happened to him. Every day he would replay the eventualities of climate change, and resource depletion, and economic collapse. He couldn’t get them out of his head. So “Church,” according to Tyler, morphed into what was essentially an elaborate form of cutting that helped John to relieve his mental anguish.

For his part, John described this ritualized form of tattooing and piercing—what those in urban queer subcultures would call BDSM play—as a time when he and Tyler could simply turn off the lights and be present to the “goddamned quiet.”

Serial Productions promotes S-Town as a story of a man who wants to make a change, who wishes to save a town: a familiar story, a hopeful one. But S-Town does not ultimately save an Alabama town, nor does it save John from having lived out his queer life in the dead center of “Trump Country,” in an Alabama county that was the last to desegregate and that still denied marriage licenses to gay and lesbian couples at the time of recording. And while critiques of the podcast’s penetration of a gay man’s private life-after-death may seem warranted, McLemore did dedicate the last years of his life to exposure, if not the “uncloseting,” prideful type to which we are accustomed.[10] Poisoned by mercury, spending his days feeling the weight of climate change and economic collapse, rubbing it raw, raving all night on the phone, and pissing in the sink, John B. McLemore wanted to be heard.

The concerns we typically circulate about storytelling and the South are not clearly applicable to S-Town. Coastal liberal hand-wringing at Reed’s “exploitation” or “misrepresentation” of Southern masculinity do not apply to this story, as there is little denial of its accuracy. Reed portrays Woodstockians as “a violent, sadomasochistic, racist, feral people,” but a vulnerable population as well.[11] The Guardian’s Matthew Teague garners local residents’ responses to Woodstock’s new image as Shit Town, and most seem to be perfectly fine with it: “‘Seemed like a pretty accurate portrayal,’ said Woodstockian Clark Alexander, as he came in to pay for gas at the grocery.” Teague continues, “No collection of humans has ever cared less what the wider world thinks of their town.”[12]

Fuck it. Reed describes this “way of moving, moment to moment, through the world,” which he sees as prevalent in Shit Town, as the “fuck it” philosophy. He contends that this is “a belief that there is no sense in worrying or thinking too much about any given decision because life is going to be difficult and unfair, regardless of what you do.”The podcast portrays John B. McLemore as a staunch opponent of the “fuck it” philosophy, a man who detested resignation, “the numb acceptance that we can’t change things,” in Reed’s words. And yet, despite the mystery, beauty, and vulnerability he uncovers in John, Tyler, and Woodstock, Alabama, Reed misinterprets John’s relationship to the act of shrugging one’s shoulders and resigning, “fuck it.” He is correct that John was a queer man who never found the kind of love you could write a country song about, or as Reed puts it, “F-150-pickup-truck love, denim-hugging-on-your-thighs love, azaleas love . . . kissing-on-your-belly-and-all-around-your-red-hair love.” As far as Reed’s investigation carries us, John never found a love like that. But he did have a queer love unrecognizable to the genre standards of country music. John found tattoo-gun-to-chest love, all-night-awake-going-mad-on-the-phone love, bourbon-and-spray-painted-initials-under-the-bridge love. And still, despite or because of all that love, he did finally shrug, “fuck it.”

John’s story is not one of a queer who could have lived otherwise, even had he moved to a city like Birmingham with its vibrant gay community less than fifty miles down I-20. S-Town is not a story about a man who died in a shit town. It’s a story about a man who lived in a shit world. An unabashed killjoy, John B. McLemore practiced a radical form of negativity, a queer relationship to the earth marked by shame, madness, and rage.[13] Operating somewhere beyond the fight against apathy, he embodied the “fuck it” philosophy, killing himself to make room in a world where there is little room left. This is a different story of being queer in the country, in Alabama, in what is now Trump’s America. With his melancholic attachment to the earth and its destruction, John wore the collective pain of environmental disaster on his body, slowly damaged and poisoned, like the rest of us. For decades, this poisoning was “tedious and brief,” and then, at the end, it came fast.

Notes

[1]Judith Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 36.

[2] Since Halberstam’s explorations of metronormativity, various scholars have accounted for queer rurality. Among them, see Colin Johnson, Just Queer Folks: Gender and Sexuality in Rural America (Philadelphia, Temple University Press, 2013); Queering the Countryside: New Frontiers in Rural Queer Studies, ed. Mary L. Gray, Colin R. Johnson, and Brian J. Gilley (New York: New York University Press, 2016).

[3]Nicholas Quah, “S-Town Has Exceeded 40M Downloads, Which Is Truly a Ton of Downloads,” Vulture, 4 May 2017, www.vulture.com/2017/05/s-town-podcast-40-million-downloads.html.

[4] Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire, ed. Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 5.

[5] Neal Broverman, “John B. McLemore Finally Escaped S-Town,” Advocate, 25 April 2017, www.advocate.com/arts-entertainment/2017/4/25/john-b-mclemore-finally-escaped-s-town.

[6] Scott Herring, Another Country: Queer Anti-Urbanism (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 23.

[7]Broverman, “John B. McLemore Finally Escaped S-Town.”

[8] Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” Collected Papers, vol. 4, ed. James Strachey and Joan Riviere (New York: Basic Books, 1959): 152–70.

[9] Erin Savage, “Water Crisis in West Virginia,” The Appalachian Voice, February/March 2014, 12–15.

[10] Bre Payton, “‘S-Town’ Podcast Goes Too Far in Digging into John McLemore’s Private Life,” Federalist, 4 April 2017, thefederalist.com/2017/04/17/s-town-podcast-goes-far-digging-john-mclemores-private-life/.

[11] Matthew Teague, “‘Pretty Accurate’: S-Towners Are Proud to Be Podcasted—Except for a Few Things,” Guardian, 9 April 2017.

[12] Teague, “‘Pretty Accurate.’”

[13] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Adam Frank, “Shame in the Cybernetic Fold: Reading Silvan Tomkins,” Critical Inquiry 21, no. 2 (Winter 1995): 496–522.

Christina Belcher received her PhD in English and Gender Studies at the University of Southern California in 2016. She continues to teach at USC, where she is working on her first book, Backward: Queer Rurality in American Culture. This work considers anti-normative rural representations, which have been used as negative examples of American citizenship, helping to forge a national consensus about cultural values regarding race, class, gender, and sexuality.