Risky Play: Swatting Streamers, or Now You’re Playing with (Police) Power

Sunday, March 6, 2016 at 7:16PM

Sunday, March 6, 2016 at 7:16PM Alexander Champlin

[ PDF Version ]

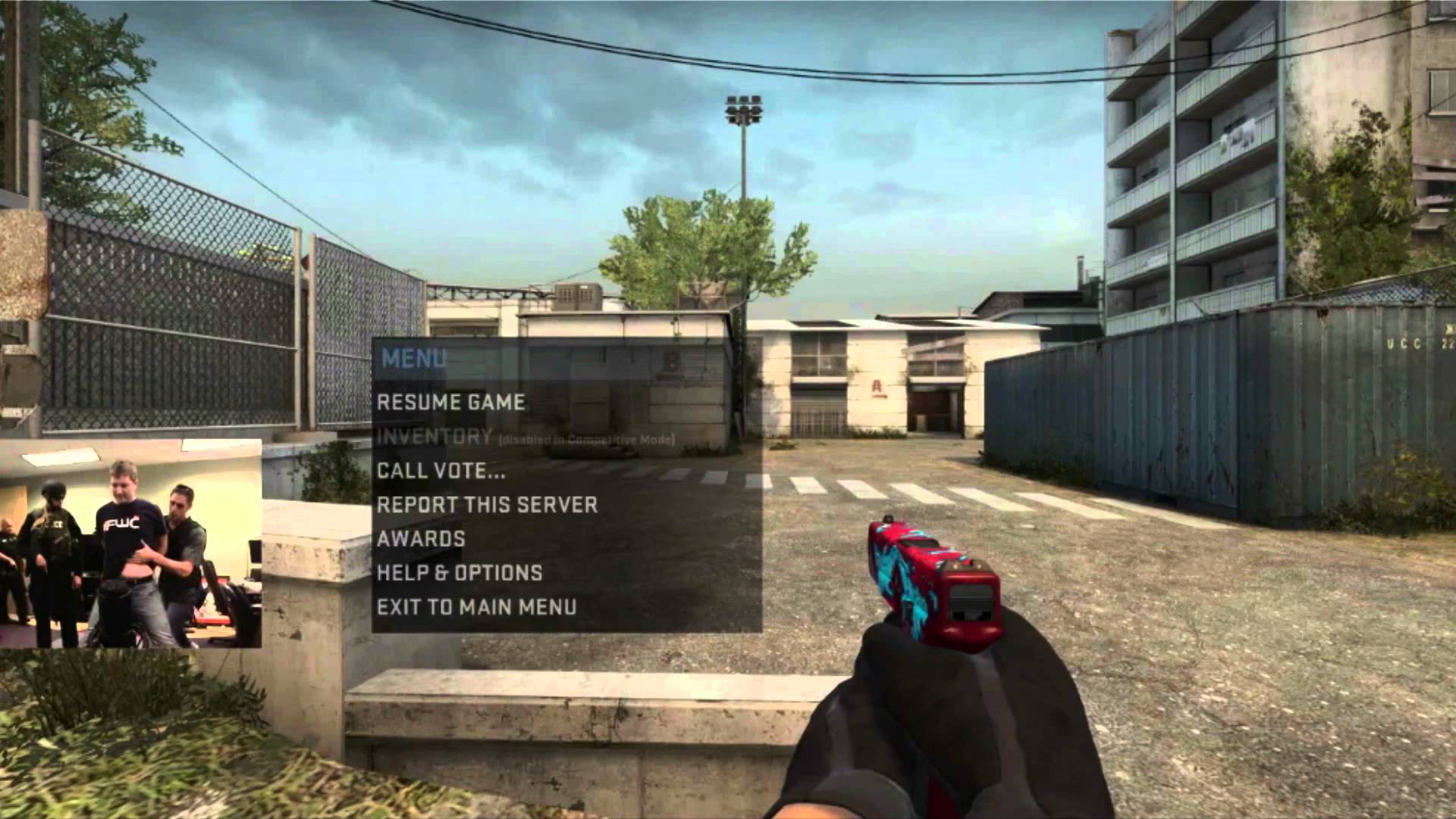

The stream looks like any of the hundreds of Counter-Strike: Global Offensive channels on Twitch.TV. The screen offers a window into Jordan “Kootra” Mathewson’s current match, a series of competitive rounds in the first-person shooter. In this game, players are cast as either terrorists or counter-terrorists and tasked with defeating the opposing force.[1] While the main action—the rounds of battle between these eternally countervailing forces—dominates the screen space of this video, a small box in the bottom left corner projects webcam video of Kootra, a young man in a red baseball hat, T-shirt, and headphones. He is one of a number of new media professionals (and amateurs), minor Internet celebrities who use videogames as a platform for content creation.[2] Kootra is known both for streaming play over live services like Twitch and generating machinima and game-related videos for YouTube with a collective called the Creatures. While Kootra is streaming, anyone on the Internet can watch him play, listen to his commentary, and participate in a text conversation that accompanies the stream.

What makes this particular stream sensational is the break in gameplay flow. Kootra is visible in the bottom corner of the screen. His webcam catches him sitting behind a desk in an office. He chats with the other players in the server between rounds of bomb missions and shootouts. Then, just as the voice on the in-game radio announces the counter-terrorists’ victory at the end of a round, Kootra turns away from the camera and removes his headphones. He is distracted by something occurring inside of the building. With a sheepish look, he turns back and tells the viewers, “This isn’t good. I think we’re getting swatted . . . [T]hey’re clearing rooms.” With a mixture of fear and amusement, he recognizes that he has become the target of a prank, but also that he is unprepared for what is coming. Almost immediately, his office door opens and police officers, dressed in full-body Kevlar and armed with assault weapons, enter the room shouting. Kootra raises his hands as the officers drag him to the floor. One officer stands on his back while three more cuff him and check the room. The scene is tense and confusing; the police members are acting with the speed and force of an emergency response. News reports after the event reveal that they believed they were responding to a shooting and hostage situation and that they arrived with an array of military-grade armaments. Because the other players in the game server are largely oblivious to this, the game continues as if nothing dramatic is going on. Kootra’s character stands idle, a spectator to the virtual battle that is reloading itself in the server. As the battle resumes, it offers a comically terrifying parallel to the mobilization of military equipment displayed on the still-running webcam.

Figure 1. Video still from the raid on Kootra.

Figure 2. Close-up of the Kootra SWAT raid.

The raid that targeted Kootra was one of many swatting attacks against videogame streamers. It is captured in its entirety thanks to the live streaming broadcast of Kootra’s gaming session and distributed across YouTube as a novel form of Internet pranksterism. I argue that the media texts that these types of raids (against gamers, captured on webcam) produce are compelling objects of analysis that reflect the permeating confluences of spectator gaming, surveillance, and police militarization. A 2008 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) news brief, “Don’t Make the Call: The New Phenomenon of ‘Swatting,’” explains that these types of pranks involve “calling 9-1-1 and faking an emergency that draws a response from law enforcement—usually a SWAT [Special Weapons and Tactics] team.”[3] Yet, swatting refers to a much larger trend than I will examine here. According to an FBI spokesperson, as many as 400 incidents of prank SWAT calls occur per year.[4] It has become a tool used anonymously to target celebrities, cultural critics, game developers in the wake of #gamergate, game players, and politicians, among others.[5] In many of these uses, the practice’s reactionary character and its power for stifling marginal voices are manifest. Swatting expresses an imbalance of power in relation to police militarization that is leveraged by an anonymous and insulated consortium of pranksters to target people remotely. In narrowing my focus to targeted live streamers, I hope to think through issues that are more difficult to pinpoint in a broader discussion of swatting.

Notably, these live stream attacks produce a new kind of interactive digital media, which is often their goal. One psychologist has explained these pranks as “kind of like creating your own episode of cops [sic].”[6] These media texts offer a startling juxtaposition between videogame worlds of military fantasy and the mis-deployment of actual military technology and American police forces. Furthermore, while the politics of this play may be somewhat obscured in the immediacy of the attacks, what ultimately emerges from these power games is an insular and uncritical view of contemporary police power.

Kootra is not the only victim of swatting whose experience was captured on webcam video and distributed online. One YouTube anthology of these attacks, “10 streamers get swatted live,” catalogues similar instances featuring video or audio of raids against Caleb Hart, a videogame speedrunner; Jordan Gilbert, a professional Call of Duty player for Cloud 9 Gaming who goes by the handle n0thing; Alexander Wachs, or Whiteboy7thst, whose raid led to a marijuana arrest; and James Varga, or PhantomL0rd.[7] Varga, a professional League of Legends player, was streaming to over 80,000 viewers when police entered his apartment. Although each raid is a unique event, they form a genre akin to the Kootra video—the interplay between casual play and the spike in tension in the presence of police, the permeation of domestic space by armed and militarized actors, and the shifting of attention from the game to the action outside of the screen. These raids become media objects that are produced by co-opting both live streams and police power and turning these forces against the players performing on camera.

In these pranks, we should recognize a disparity between the understandings of martial power at work and its violent actualizations. The videogame shooter takes a casual, playful relationship to military power. While swatting also hinges on fantasies of police power, these fantasies are significantly misaligned with the actual force of these SWAT units. The interplay between the fantasy and the actuality signals a dangerously blasé understanding of trends toward police militarization. These pranksters are participating in a game with stakes that appear game-like, but which have far more material consequences when we consider swatting in relation to broader tendencies in police deployment. In particular, the stark racial imbalance of police violence distributes the stakes of threat and bodily harm disproportionately. Ultimately, the juxtaposition of mobilized SWAT units in these videos and their virtual counterparts highlights the incongruities between game representations and the militarizing effects of risk management and police armament.

Figure 3. Still from “10 streamers get swatted live,” a video anthology of notable swat pranks.

Watching Swatting: Serious Risk and Playful Banality

As texts, these raids are exceptional, but they are also improvised interventions of a single actor in a systemic assemblage of media and police mechanisms. Twitch.TV provides a nearly unlimited supply of unwitting victims sitting in front of cameras broadcasting over the Internet. Concurrently, to date, government legislation has equipped over 8,000 local police units with the equipment necessary to respond to emergencies with the tactics and weapons of a small military unit.[8] The production of a swatting video then only requires one technically proficient and brazen (albeit shortsighted) actor to bring these systems together.

What pranksters prey on is an inability to differentiate between an actual emergency and a manufactured story. These pranks exploit a climate of increased police preparation against the backdrop of highly visible threats like terrorism, killing sprees, and drug violence. SWAT hoaxes construct terrifying and familiar narratives that are unverifiable but demand to be taken seriously. Moreover, they activate the institutional trappings of a political and juridical system increasingly equipped to forcefully deal with these risks.[9] The swatting perpetrators achieve this by tapping into the broader system organized around risk management that Ulrich Beck has called the “risk society.”[10] As the politics of a risk society makes SWAT units more visible and technologically potent, this tendency in risk management also makes them increasingly appealing tools in escalating games of Internet prankishness. The movement of this military technology into the domestic sphere, through government programs and local law enforcement grants, and the visibility of these technologies in coverage of the Ferguson protests and Occupy movement or in episodes of COPS, make these technologies tantalizing tools for misuse. Against the politics of a risk society and the milieu of highly publicized police violence, swatting pranks exploit these systems for personal pleasure or popular notoriety. In the course of this play, swatters reveal a privileged irreverence about police militarization and apathy toward the risks these powers claim to safeguard against.

Amidst this climate of seriousness and risk, swatting poses an incompatible atmosphere and re-inscribes affects of ambivalence and uncaring. At their most politically pointed, SWAT pranks may be read as a refusal to buy into the logic of the risk society—are they instantiations of risk management or overzealous preparation for a virtual threat? At their least informed, these pranks misunderstand the power and potential of military equipment and tactics. They confuse the toothlessness of videogame arms with the real, if unevenly deployed, potency of SWAT training and gear. In this way, these pranks become more like the videogame fantasies of military play and competition that they interrupt, only with far more real consequences.

Two theoretical frames are especially productive to consider here. The first is Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter’s discussion of videogames and “banal war,” a concept that they adapt from Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Empire. Banal war refers to a state in which war becomes perpetual, the enemy and the fighting are diffuse, and the culture of daily life is oriented around this conflictual totality. For Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, banal war offers a way to think about the military shooter game as a feature of contemporary culture that familiarizes players with war and strips it of its stakes.[11] In the case of swatting streamers, this banality results from the omnipresence of military and police tactics and technologies. As their real and virtual deployments pervade the domestic spaces of streamers and spectators, their boundaries grow more nebulous. In this respect, an atmosphere of banal war could explain how something as serious as a SWAT unit can become a game in an otherwise low-stakes power play between pranksters and players.

Matthew Thomas Payne’s concept, “ludic war,” offers a second theoretical frame for this discussion.[12] The key referent for Payne is Robin Luckham’s idea of “armament culture.”[13] Distinct from a culture of militarism and militarization, armament culture produces a fetishization of advanced weapons and military systems, if not necessarily an importation of the values of a warlike culture. For swatting, this might allow some insight into the phenomenon as an emergent social practice that aestheticizes the power of SWAT units without buying into the narratives of imminent danger and police vigilance that rationalize their budgets. Based on their YouTube retellings, the targets of swatting may feel some pleasure in encountering police technology, even if their experiences are largely terrifying. The testimonies of targets also suggest that there is a cachet in recounting these experiences, especially the parts that feature the police and their gear, to fans.[14] Likewise, the spectators of these pranks may gain pleasure in seeing these technologies mobilized as a game and appreciate the practice as an elaborate prank. Much of the cachet of swatting videos derives from their successful play, which is measured by the strength and visibility of the police response. If we think of these attacks in terms of ludic war, we might better comprehend the playful atmosphere that surrounds the pranks and the fascinations with the technology that accompanies them. So, while swatting does not have to embrace police militarization as a political necessity through the logic of the risk society, it recognizes this development as an opportunity for mischievous misuse. Military game logics prevail here, but not necessarily as a wholesale endorsement of militarism. Instead, the logics of self-centered play and mastery arise most clearly in the spectatorship of swatting pranks and facilitate the misrecognition of stakes.

Together, these theories suggest that we read swatting attacks as a playful (albeit dangerous) disavowal of risk society logics in the service of a personal and public game of power. They emerge out of a comfort with tendencies towards domestic militarization without (fully) buying into the rationales of security and necessity that initially bring police technology into American domestic spaces. Indeed, it may even be the heightened visibility of these technologies across media that mythologizes and mystifies their actual power. Likewise, in a field of ludic war, these technologies are easily remapped as tools for competition and mastery between players whose games traverse the bounds of virtual play space. For the architects of these pranks and for onlookers, this marks a shift between the game and webcam screens that are both contained in the streaming broadcast. For victims, the stakes of this play are far more real. In many of their accounts, they struggle to reconcile the playfulness and excitement of the raid against the palpable danger that SWAT teams pose to them.[15]

Swatting Streams, Streams of Power

Ultimately, swatting is a fascinating and frustrating media phenomenon that relies on a worrisome confluence of contemporary developments. In the spirit of Ulrich Beck’s critique of the risk society, swatting might satire the inflated language of risk and the Wars on Drugs and Terror if pranksters can so easily misuse these security tools. However, it also reveals a dangerous vulnerability when these powers become mythologized and enable their misrecognition as a kind of “power-up.” This is a privileged relationship to military potential that only appears to be held at the distance of the virtual. It is a view of the SWAT team that sees it through news, television, and videogames rather than at the sites of its actual deployment. Therefore, instead of achieving a cultural critique of police power and discourses of risk, these videos attest to games of ego and fantasy that unfortunately play into the banalization of police militarization.

It is striking that swatting pranks are emerging at a moment when SWAT units confront protesters and broader concerns about the proliferation of military equipment are generating more vigorous public debate. The attack on Kootra in Colorado occurred just days after SWAT units and military technology were deployed in Ferguson, Missouri to quell protestors who were rallying against a culture of radicalized police violence. The act of swatting streamers co-opts these forces for personal plays of power rather than challenging their misuse. For many, especially those who belong to vulnerable and stigmatized racial, ethnic, and gender categories, increasing police militarization poses an asymmetrical and violent threat. However, for privileged players familiar with militarization through virtual banality, these forces are too easy to misrecognize. Thus, participating in or watching swatting calls for a consideration of this uneven topography. It is a space in which the fantasies of military technology and its material deployment in domestic spaces aggressively collide. They allow us to see the fraught effects of the risk society and banal war, especially when these outlooks are shaping the material deployments of power.

Notes

[1] “‘KOOTRA SWATTED FULL VIDEO’ ‘Member of Creatures’ ‘Littleton Swatt video’ ‘The creatures swatted’” YouTube, uploaded by Blade Cinema, Aug. 27, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uH-uRFIr3mA.

[2] T.L. Taylor has written extensively on the professionalization of videogames and e-sports. Other key voices include Dal Yong Jin and Nicholas Taylor. See Dal Yong Jin, Korea’s Online Gaming Empire (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009), T.L. Taylor, Raising the Stakes: E-Sports and The Professionalization of Computer Gaming (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015), and Nicholas Taylor, “Play to the camera: Video ethnography, spectatorship, and e-sports,” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies (2015): 1-16.

[3] The prank is a form of social engineering with roots in phone-phreaking. “The New Phenomenon of ‘Swatting.’” Federal Bureau of Investigation, Feb. 4, 2008. http://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/2008/february/swatting020408.

[4] Adrianne Jeffries, “Meet “swatting,” the dangerous prank that could get someone killed,” The Verge, Apr. 23, 2013, http://www.theverge.com/2013/4/23/4253014/swatting-911-prank-wont-stop-hackers-celebrities.

[5] Grace Lynn, a game developer and critic of Gamergate, was targeted when someone sent a SWAT team to her former address. See Adi Robertson, “‘About 20’ Police Officers sent to Former Gamergate Critic’s Former Home after Fake Hostage Threat,” The Verge, Jan. 4 2015, http://www.theverge.com/2015/1/4/7490539/fake-hostage-threat-sends-police-to-gamergate-critic-home.

[6] Erik Ofgang, “Connecticut Man Faces “Swatting” Charges; Fake Crises but 911 Responses,” Connecticut Magazine: Connecticut Today, Sept. 22, 2014, http://www.connecticutmag.com/Connecticut-Magazine/October-2014/Connecticut-Man-Faces-Swatting-Charges-Fake-Crises-but-911-Responses/.

[7] “10 streamers get swatted live,” YouTube, uploaded by CrowbCat, Oct. 22, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TiW-BVPCbZk.

[8] “1033 Program, FAQs,” Defense Logistics Agency. http://www.dispositionservices.dla.mil/leso/pages/1033programfaqs.aspx

[9] While this backdrop of catastrophe structures the viability and potency of swatting pranks, it also serves as the logic for arming SWAT teams. In the wake of the September 11th attacks, federal resources for domestic police units have increased dramatically, largely through the 1033 program. See "SEC. 1033. TRANSFER OF EXCESS PERSONAL PROPERTY TO SUPPORT LAW ENFORCEMENT ACTIVITIES” in "PUBLIC LAW 104–201—SEPT. 23, 1996. National Defense Authorization for Fiscal Year 1997," National Park Service, http://www.nps.gov/legal/laws/104th/104-201.pdf. More funds have also been made available through the Department of Homeland Security. See “Find and Apply for Grants,” Department of Homeland Security, http://www.dhs.gov/how-do-i/find-and-apply-grants and Andrew Becker and G.W. Schulz, “Local Police Stockpile High-tech, Combat-ready Gear,” Center for Investigative Reporting, Dec. 21, 2011, http://cironline.org/reports/local-police-stockpile-high-tech-combat-ready-gear-2913.

[10] Ulrich Beck, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity (London: Sage Publications, 1992).

[11] Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter, Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009).

[12] Matthew Thomas Payne, “F*** You, Noob Tube!,” in Joystick Soldiers: The Politics of Play in Military Video Games, eds. Nina B. Huntemann and Matthew Thomas Payne (New York: Routledge, 2010), 206-223.

[13] Robin Luckham, “Armament Culture,” Alternatives 10 (1984): 1-44.

[14] See three examples of accounts of swatting from the victims: OpTicBigTymeR, a Call of Duty pro player, and Woody and ZweebackHD, both Twitch streamers and YouTube Let’s Play content creators. “What ACTUALLY Happened with OpTic and the Police....” YouTube, uploaded by OpTicBigTymeR, Nov. 5, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I5A-D0zNhFw; “Greatest Story Ever Told Part 1 - Woody Swat Team,” YouTube, uploaded by WoodysGamertag, Mar. 16, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ERUArsRV1Xc; and “How I Got Swatted,” YouTube, uploaded by ZweebackHD, Feb. 7, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N4s_3Ls82ao.

[15] In each of their accounts, OpTicBigTymer, Woody, and ZweebackHD retell the story of their raids in thrilling detail in follow-up video posts. These accounts emphasize the danger and shortsightedness of the attacks and describe their harrowing experiences of police confrontations, which conflates the senses of excitement and caution.

Alexander Champlin is a PhD candidate in the Department of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He studies spectator videogaming as an emergent media phenomenon. He is interested in the ways that play and game cultures shift as games become broadcast texts.

Reader Comments