Regulating the Cloud and Defining Digital Markets

Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 9:40PM

Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 9:40PM Jennifer Holt

[ PDF Version ]

The cloud has become a component of media distribution in the digital age with qualities that we have yet to fully grasp, particularly in relation to its functionality, security, and the principles we might use to regulate its operation. These elements and the integral privacy issues at stake are of course wholly intertwined with the foundation of regulatory constructs for the digital ecosystem, or what might be called cloud policy. When we think about regulating the cloud, particularly in relation to its media applications, we are in part thinking about how policy is created for managing digital data, and for the infrastructure that supports the storage and distribution of such data. Other related issues include the jurisdiction over data in internationally located servers, the policies governing remote storage and server farms, and even the telecommunications laws regarding broadband classification and net neutrality. These global considerations are all part of the landscape of cloud policy and the viability of media markets in the Internet era.

However, it is also important to recognize in any emerging regulatory paradigm that the markets being policed are unique. That is because they are largely digital. Of course, there are many physical, geographically located, earthbound dimensions of their infrastructure and operations.[1] Nevertheless, the preponderance of their distinctly digital characteristics and functions compel us to think about how we might define digital markets—or those markets rooted in digital distribution and dissemination—differently than their analog counterparts for regulatory purposes. Are there macroeconomic principles that should be considered for their specific properties? This broader question has come up before, notably in the 1930s and 1940s. At that time, in the wake of tremendous industrialization, socioeconomic changes, and labor transformations, the economic approach to regulation in the United States changed into a more tailored one rooted in the concerns of particular markets instead of remaining a largely one-size fits all standard. Market-specific agencies like the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) were created to determine guidelines and policies adapted for each industry, designing regulatory principles specifically formulated for each economic sector. Perhaps, in this contemporary time of transformation brought on by digital technologies and related cultural, economic, and industrial shifts, it is once again time to apply those same principles of policy differentiation to digital markets.

The digital media industries are a single industry; there are multiple businesses striving for market power at once in the digital media space, from content companies and studio-based distributors to identity intermediaries, broadband providers, and even hardware companies that have proprietary software platforms for digital media distribution (e.g., Apple and iTunes). A rethinking of market definitions would force regulators to create paradigms that are more appropriate to products, processes, and players operating in the digital space as opposed to those solely rooted in specific geographic locations and physical conditions. Perhaps the market for streaming video requires different macroeconomic principles and considerations than that of first-run domestic theatrical film, broadcast network exhibition, or cable syndication. It has been said in Hollywood that “the motion picture business is like any other business, only more so.” Does it then follow that digital markets are like any other markets, only more so? Or are they entirely different?

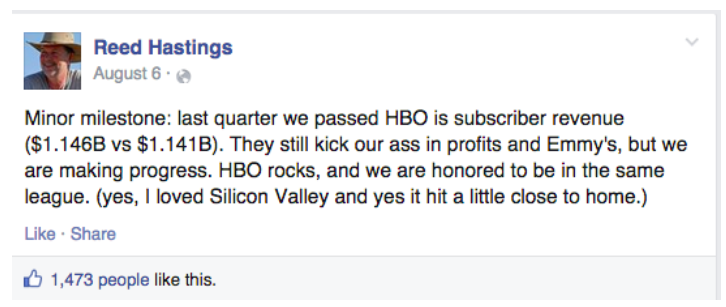

The role of the cloud in defining market parameters for the current media landscape is a generative place to begin answering this question. Due to the increasing role that mobile technologies and connected viewing strategies are playing in our media culture, cloud storage has become an essential element of digital media distribution, whether it is to support streaming options on Netflix or to store purchases made through iTunes. In addition to serving as infrastructure for digital distribution, the cloud has also significantly affected market function and performance in the media industries. Remote storage and streaming media platforms have altered and, in many ways, expanded the space for competition; in the home video arena, Netflix has generated a bigger subscriber base in the last ten years than HBO was able to amass in the last thirty, and Netflix recently surpassed HBO in revenues, though not in profits.[2]

Netflix CEO Reed Hasting’s Facebook post from August 6, 2014

At the very least, there is more competition for audiences with the introduction of digital distribution. Cloud-based media have also helped redefine certain viewing practices as being more valuable than others in terms of ratings and engagement. Supply, demand, pricing, and even production have all been reconfigured by the insertion of the cloud into the various markets for film and television content as well. It is clear that the cloud has become a key force shaping the economies of competition and market behaviors in the film and television industries of the future. It is less clear exactly how to quantify or account for the totality of this impact.

Traditionally, media markets have been measured in financial terms, conceptualized with national or regional boundaries, segregated by medium, and divided into various windows such as domestic theatrical, home video, and electronic sell-through (EST). Various studies of film and television have detailed the increasing complexity of distribution and market dynamics in the digital era.[3] Patrick Vonderau has offered one productive and concise view of how markets are usually defined, explaining that they are “variously described as collections of viewers or media artifacts, devices per household, playdates per territory, geographical regions, social networks, institutions, techniques for managing demand, or as the sum total of transactions in a given time and space.”[4] Going beyond these more traditional definitions, Ramon Lobato’s rich and rigorous book Shadow Economies of Cinema explores informal economies and markets outside the purview of the state that have cropped up, many of which exist in digital space.[5] With these various dimensions in mind, I would like to highlight a few key principles that have already been altered by cloud-based digital distribution and mobile platforms/screens with the goal of identifying how we might begin rethinking the contours of contemporary media economies.

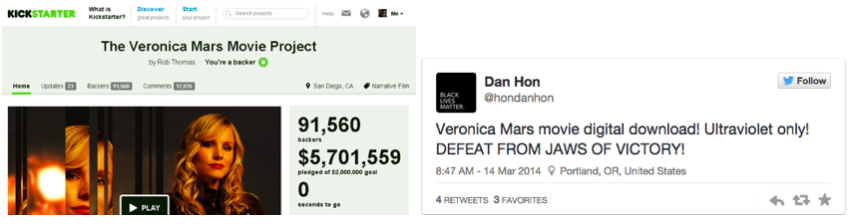

Supply and Demand

Supply and demand act as the most basic components of commodity valuation in a market. Do they function the same way in the digital distribution ecosystem when, for example, there is no finite number of prints that can be struck, and no fixed prime-time programming schedule to consider? There are limits on these constructs in the digital space to be sure: supply is often unstable and frequently fluctuating due to licensing deals; the shifting role of distributors, tensions between content providers and digital platforms; and distributors’ lingering uncertainties about the most effective and strategic way to utilize digital windows. Sometimes technology creates instability simply by getting in the way of supply meeting demand. The difficulty that Warner Bros. had getting Kickstarter contributors their early Veronica Mars downloads is one unfortunate example. The supply models for when and on what platform content is released are still being formulated, and there are some basic protocols for domestic digital windows, but it seems there are often more exceptions than rules.[6]

VERONICA MARS Kickstarter – Unhappy Customers

Demand is similarly inconsistent because of shifting consumer habits and expectations, along with a lack of clarity regarding technologies and availability. Audiences might know they want to watch the new season of Damages on a digital platform, but they don’t typically know when they can access it, or where they can watch it. Consequently, a significant variable in this landscape is consumer awareness. There is simply less demand for something if people don’t know it’s there. There is also much greater demand for digital product in general than content companies are willing or able to meet with supply, particularly in international markets.[7]

Scarcity, Abundance, Efficiency, and Waste

The cloud has complicated this equation further by creating what appears to most casual observers as a capacity for endless supply, but frustrating consumers with the very human, analog, physical and contingent infrastructure that is anything but limitless. Despite the corporate promotion of “cloud computing” and “cloud storage” as abstract, celestial panaceas for managing an infinite amount of digital content, there are still considerable concrete, earthbound challenges for this cloud infrastructure as the demand for access to offsite data continues to explode. That is because ultimately digital markets are very physical. The cloud depends on buildings, computers, servers, wires, routers, switches, cables, pipes, hard drives, and workers who maintain and service this infrastructure. Moreover, the studios and human capital supplying much of the high-end content are still rooted in Southern California, and many of the high-tech companies supporting cloud infrastructure and innovating digital platforms are similarly ensconced in Silicon Valley.

Yet, digital delivery continues to push the boundaries of market size and scale beyond what was ever possible with physical products. In so doing, digital media markets have also altered our concepts of scarcity and abundance, and created new attitudes about related issues such as efficiency and waste. The broadcast industry largely operates on principles of scarcity: the electromagnetic spectrum is finite and stations have to occupy a solitary position on their slice of it in order to function. That is also the reasoning behind regulating this business and medium in the public interest: the US government has given private companies monopoly squatting rights over the limited resource of the publicly owned airwaves. In exchange for their unmitigated power over our culture, communication, and information, as well as almost $70 billion in advertising revenues, broadcast networks are supposed to be responsible to the public, imagined as the spectrum landlord. The film industry has also historically enjoyed exploiting the concept of scarcity, whether in the production sector by cornering the market on specific talent and certain stars, in distribution with the use of limited release strategies and various windowing practices, or in exhibition with exclusive engagements and special screenings.

Map of the U.S. Radio Spectrum

The digital space, however, is built upon the premise and promise of—indeed on the widespread cultural perception of and investment in—abundance. Yet this abundance is limited in many ways by scarcity: scarcity of bandwidth, scarcity of certain content, scarcity of access to unfiltered information, and scarcity of privacy. Cable technology with its 500-channel universe was certainly a move toward abundance, but the consolidation of multi-system operators (MSOs) and content providers has demonstrated just how scarce properties like diversity and competition can become when a company like Comcast wires 30 percent of American cable homes, owns sixteen major cable networks and has behaved in illegal, anticompetitive fashion in the digital marketplace with no repercussions beyond a slap on the wrist from the FCC.[8]

As audiences, whether we approach this environment with a psychology of scarcity or of abundance—which usually differs based on a variety of demographic factors—determines how we value our time in the digital environment, as well as how we value the products of digital markets. That psychology of scarcity or abundance on the part of regulators will also determine how markets will be controlled, or not. If the ethos of abundance is what guides policy, digital markets will likely have more freedom from government intervention and consumers/users will likely have less protection from those same agencies. If regulators focus on what is actually scarce in this ecosystem, perhaps such values as privacy, access, competition among providers, etc. might be afforded a bit more attention.

Competition, Market Compression, and Market Expansion

The understanding of competition in the digital space also seems to have different or more fluid parameters than physical markets, as do the concepts of market compression and expansion. The determination of whether a market is competitive, concentrated, open to new entrants or not has traditionally been made by using formulas such as the Herfindahl-Hirshman Index, or HHI, which is widely accepted especially by regulating agencies focusing on antitrust and mergers like the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. However, these measurements are contingent upon how a market is defined. Take, for example, the home video market: is it comprised of just DVD and cable and satellite-based Video-On-Demand? Or does it also include Subscription Video-On-Demand (SVOD) services like Netflix, EST platforms such as iTunes, and streaming platforms like Hulu? If you ask the growing number of cord-cutters—consumers who view cable programming without subscribing to cable services—their answer would be a resounding yes, but these questions have yet to be formally decided by policy or case law. Nevertheless, the longer and more expansive the chain of buyers and sellers, and the larger the pool of firms understood to be participating in a particular market, the less likely that market is to be determined anti-competitive or overly concentrated to the point where the government makes a regulatory intervention. Therefore, the questions of market definition will necessarily impact whether they can be labeled “anticompetitive” or not, and consequently how much protection will be afforded to consumers.

Market Limitation

Market limitation is the practice of building institutional structures that effectively limit external competition without engaging in more obviously illegal practices like price fixing or block booking that would be more easily actionable under antitrust law.[9] This is happening in the digital space on multiple fronts, by Internet Service Providers, hardware companies, and even content providers. Market limitation is embedded in restrictive licensing terms or in the refusal to license content, in windowing strategies, and in throttling practices, as many ISPs have already done in order to limit the activity of what they call bandwidth hogs.[10] Even bandwidth caps can be a limiting device—Comcast, for example, does not charge against bandwidth limits when it is their proprietary content being streamed over Xbox and other devices served by Comcast wires, giving their own networks a potentially significant ratings advantage. These are just a few of many ways in which competition in a digital market can be limited, and it is often by players or providers who are technically outside the market in question: a broadband provider limiting competition in the content arena, for example.

Roles and Functions

Companies in digital markets often have roles and functions that are fundamentally unique to the digital ecosystem and often different or more expansive than their physical counterparts. For example, Netflix and Amazon are digital media distributors to be sure, but at their core they are data analytic engines.[11] This necessarily relates to the issue of market definition, because Netflix and Amazon are considered to be digital distribution platforms, or marketplaces, and now even content creators, but their role in data analytics is rarely discussed in relation to how it affects market behavior or company performance. At the very least, data analysis allows these digital players to have very significant strategic and competitive advantages that other firms in their industry simply don’t have. Their analytic capacity and search utilities can also serve gatekeeping functions or influence consumer decisions in ways that are rarely accounted for, but certainly beg further investigation.

The shifting role of digital platforms in this era of retransmission consent, Aereo, net neutrality battles, and other struggles related to the legacy structures of media industries highlight the fact that most digital platforms do not necessarily aspire to be cable channels. They want to be the MSOs. Digital platforms want to be the pipelines, the conduits, and the delivery systems for the content they create, eliminating the middleman. How these battles play out will significantly affect digital media markets. Also central to the discussion about roles and functions are the various intermediaries in the digital market, the most famous of which are content delivery networks (CDNs), such as Akamai, Level 3, Amazon CloudFront, or Limelight. This category of company both evades regulation and often defies comprehension but they affect markets dramatically in the sense that they distribute content more efficiently and quickly, and they also serve as a workaround to any net neutrality requirements. There are other intermediaries to consider such as identity service providers,[12] and even a new class of third-party providers involved in surveillance activity and data gathering. Companies of this class all have a tremendous influence on markets while remaining on the periphery of the cultural radar and regulatory landscape.[13]

Public and Private

The relationship between the public and private sectors has also become increasingly blurred in digital cloud-based markets, particularly with respect to infrastructure. This could pose significant problems in the regulatory sphere and elsewhere as these markets continue to develop. Presently, cloud services, even those that serve the public sector, are largely privatized. Data centers that handle storage and transmission for the government (and their public) are largely in private hands. Amazon Web Services, the leader in this space, hosts cloud services for the CIA, the Department of Defense, the US Federal Reserve, and the Navy, to name a few major government clients. Infrastructure so critical to the functioning of our society being privatized and consolidated in the hands of a few major providers has serious potential to end up like the market for Internet Service Providers: another digital market of sorts that is highly concentrated, largely unresponsive to consumer demand or regulators, and operating well outside the parameters of what could ever be labeled “in the public interest.” Unmitigated concentration of course also brings with it severe global economic, legal, and political consequences for the free flow of data around the world. Additionally, it begins to invite more centralization of infrastructural authority, which is a troubling move in the direction away from the original end-to-end architectural principle of the Internet. As the public/private distinction becomes blurred in digital markets, so do the purpose and goals of regulatory policy. It is true that our public airwaves have been in the hands of private corporations from the inception of commercial radio, and this is one way in which digital media markets and firms are definitely following in the footsteps of their predecessors.

Metrics, Measurement, Security, Piracy, Sustainability, Privacy, and Diversity

There are many more dimensions that are relevant to consider, such as metrics, measurement, security, piracy, sustainability, privacy, and diversity in the digital space. Some of these aspects of digital markets are related to recent events like the hacks on Sony[14] and Apple’s iCloud,[15] which have demonstrated just how difficult it is to protect the products of digital markets, even when they bleed into the physical. Others point to the challenges inherent in counting and accounting for digital viewership, determining the value of digital products, or dealing with imbalances in access. Ultimately, these issues are all about the relationship between media infrastructure, market power, industry dynamics, and cultural experience in the digital era. Government responsibility for overseeing this space has grown exceedingly more complex as the cloud covers more territory in markets that were formerly analog. Protecting consumers, and defending the health and vibrancy of those markets, will also become more challenging until and unless more adaptations are made to policy frameworks for the digital age.

Notes

[1] See Vincent Mosco, To the Cloud: Big Data in a Turbulent World (Boulder, CO: Paradigm, 2014); Jennifer Holt and Patrick Vonderau, “Where the Internet Lives: Data Centers as Cloud Infrastructure,” Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, eds. Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2015); James Glanz “Power, Pollution and the Internet,” New York Times, 22 September 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/23/technology/data-centers-waste-vast-amounts-of-energy-belying-industry-image.html; and Greenpeace Report “How Clean is your Cloud?” among others.

[2] Lauren C. Williams, “How Netflix is Taking the News of HBO’s Streaming Subscription,” Think Progress, 16 October 2014, http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2014/10/16/3580491/netflix-hbo-cbs-streaming/.

[3] See for example Dina Iordanova and Stuart Cunningham, Digital Disruption: Cinema Moves On-line (St. Andrews: St. Andrews Film Studies, 2012); Ramon Lobato, Shadow Economies of Cinema (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012); Alisa Perren, “Rethinking Distribution for the Future of Media Industry Studies,” Cinema Journal 52, no. 3 (Spring 2013), 165–71; Chuck Tryon, On-Demand Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2013); and Michael Curtin, Jennifer Holt, and Kevin Sanson, eds. Distribution Revolution: Conversations about the Digital Future of Film and Television (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).

[4] Patrick Vonderau, “Beyond Piracy: Understanding Digital Markets,” Connected Viewing: Selling, Streaming, & Sharing Media in the Digital Age, eds. Jennifer Holt and Kevin Sanson (New York: Routledge, 2014), 99–123, 102.

[5] See Vonderau “Beyond Piracy”; Lobato, Shadow Economies of Cinema; Richard Barbrook, “The Hi-Tech Gift Economy,” First Monday 3, no. 12 (December 1998), http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/631/552; Lawrence Lessig, Free Culture (New York: Penguin Press, 2004); Lawrence Lessig, Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy (New York: Penguin Press, 2008); and Jonathan Sterne, MP3: The Meaning of a Format (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012). These authors have discussed how the “gift economy” of the Internet as well as various forms of piracy have altered digital markets and problematized the very concept of “legitimate” markets. While questions of market legitimacy are undoubtedly crucial to this discussion, they are a bit beyond the scope of this admittedly brief piece.

[6] Susanne Ault, “Studios Find Their Best Hope for Offsetting a DVD Decline,” Variety, 6 September 2013, http://variety.com/2013/biz/news/dvd-sales-decline-effect-studios-1200600256/.

[7] See, for example, Vonderau, “Beyond Piracy”; Michael Curtin, Yueh-Yuh Yeh, Darryl Davis, Wesley Jacks, and Yongli Li, “Connected Viewing in China,” Connected Viewing Initiative: Year 2 Final Report (Warner Bros. Home Entertainment, University of California Santa Barbara, 2014); “Interview with Anders Sjöman,” Media Industries Project, 6 January 2014, http://www.carseywolf.ucsb.edu/mip/article/interview-anders-sjöman.

[8] Tony Romm, “Comcast Spreads Cash Wide on Capitol Hill,” Politico, 9 March 2014, http://www.politico.com/story/2014/03/comcast-cash-spread-wide-on-capitol-hill-104469.html.

[9] For thoughtful treatments of this concept, see Thomas Streeter, Selling the Air: A Critique of the Policy of Commercial Broadcasting in the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 198–201 and Susan Crawford, Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013).

[10] Jon Brodkin, “Verizon: We throttle unlimited data to provide an ‘incentive to limit usage,’” Ars Technica, 5 August 2014, http://arstechnica.com/business/2014/08/verizon-we-throttle-unlimited-data-to-provide-an-incentive-to-limit-usage/.

[11] Phil Simon, “Big Data Lessons from Netflix,” Wired, March 2014, http://www.wired.com/2014/03/big-data-lessons-netflix/.

[12] Kashmir Hill, “Google's Eric Schmidt Says Plus Is An 'Identity Service' Not A Social Network,” Forbes, 29 August 2011, http://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2011/08/29/googles-eric-schmidt-says-plus-is-an-identity-service-not-a-social-network/.

[13] For a detailed look at this category of providers, see Joshua Braun, “Transparent Intermediaries: Building the Infrastructures of Connected Viewing,” Connected Viewing, 124–43.

[14] Michael Cieply and Brooks Barnes, “Sony Cyberattack, First a Nuisance, Swiftly Grew Into a Firestorm,” New York Times, 30 December 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/31/business/media/sony-attack-first-a-nuisance-swiftly-grew-into-a-firestorm-.html.

[15] Sean Gallagher, “What Jennifer Lawrence can teach you about cloud security,” Ars Technica, 1 September 2014, http://arstechnica.com/security/2014/09/what-jennifer-lawrence-can-teach-you-about-cloud-security/.

Jennifer Holt is Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara and Faculty Associate at the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. She is currently working on a book entitled Cloud Policy about the regulation of digital media infrastructure as it relates to privacy, data security, and the jurisdiction of data in the cloud. She is the author of Empires of Entertainment (Rutgers, 2011) and co-editor of Distribution Revolution (University of California Press, 2014); Connected Viewing: Selling, Streaming & Sharing Media in the Digital Age (2013); and Media Industries: History, Theory, Method (Blackwell, 2009). Her work has appeared in journals and anthologies including Cinema Journal, Jump Cut, Moving Data, and Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures. She is also a co-founder of the Media Industries journal, the first peer-reviewed, multi-media, open-access online journal that supports critical studies of media industries and institutions worldwide.

Reader Comments