Reframing Colonial Legacies of New Guinea Art: Critical Curation at the Tropenmuseum

Saturday, March 21, 2020 at 8:17PM

Saturday, March 21, 2020 at 8:17PM Marion Cadora

[ PDF Version ]

In the course of its history, the Tropenmuseum has reinvented itself several times. It began as a nineteenth-century colonial collection held in Haarlem, the Netherlands. In 1910, it became part of the Colonial Institute Association and was then later transferred to a new building at the heart of Amsterdam where it is still housed today.[1] The most recent transformations began in 2009 when the museum transitioned from a “colonial institution” to one which is “explicitly self-reflexive."[2] Since this most recent transition, curators have begun examining the “laws of objects and display,” slowly working to change the way objects are displayed, partially through the work of interdisciplinary collaborations with scholars, lawyers, cultural practitioners, and activists. One such collaboration occurred in 2015 with the activist group Decolonize the Museum. They helped re-write labels throughout the Tropenmuseum’s permanent exhibit, critically examining the colonial histories associated with the collection’s provenance.[3]

The work of the Tropenmuseum is significant given growing and urgent calls to decolonize museums, dismantle myths surrounding the supposed neutrality of colonial heritage, and to analyze the way ethnographic museums have historically functioned as a window on the world undisturbed by history and politics. But is it possible to decolonize a space that is so intricately tied to colonialism? If a museum is now curated in a way that appears self-reflexive, aware of its own complicity in the colonial project, then does the museum itself become the object of repair, rather than the colonial relation?

In part, this paper considers the distinctions between institutional decolonization and reconciliation and locates the role of curatorial and museum practice within such debates. Specifically, this article explores the role of photographic media throughout the permanent display of the Tropenmuseum and the particular curatorial decisions that decenter the neutral expectations of the collections. Photography in ethnographic spaces traditionally function as a realist tool of imperial representation governance, neglecting to problematize either its photographic agenda or situated display. On the contrary, the Tropenmuseum strategically uses their photographic collections to recode assumptions of neutrality by offering various viewing experiences that reveal the epistemological basis of its own institutional discourse, which for two hundred years mainly centered on a meticulously accumulated and categorized set of colonial objects. This article shows how the museum politicizes and reinvents colonial heritage and suggests the limits of such projects.

Counter-Positioning Photography

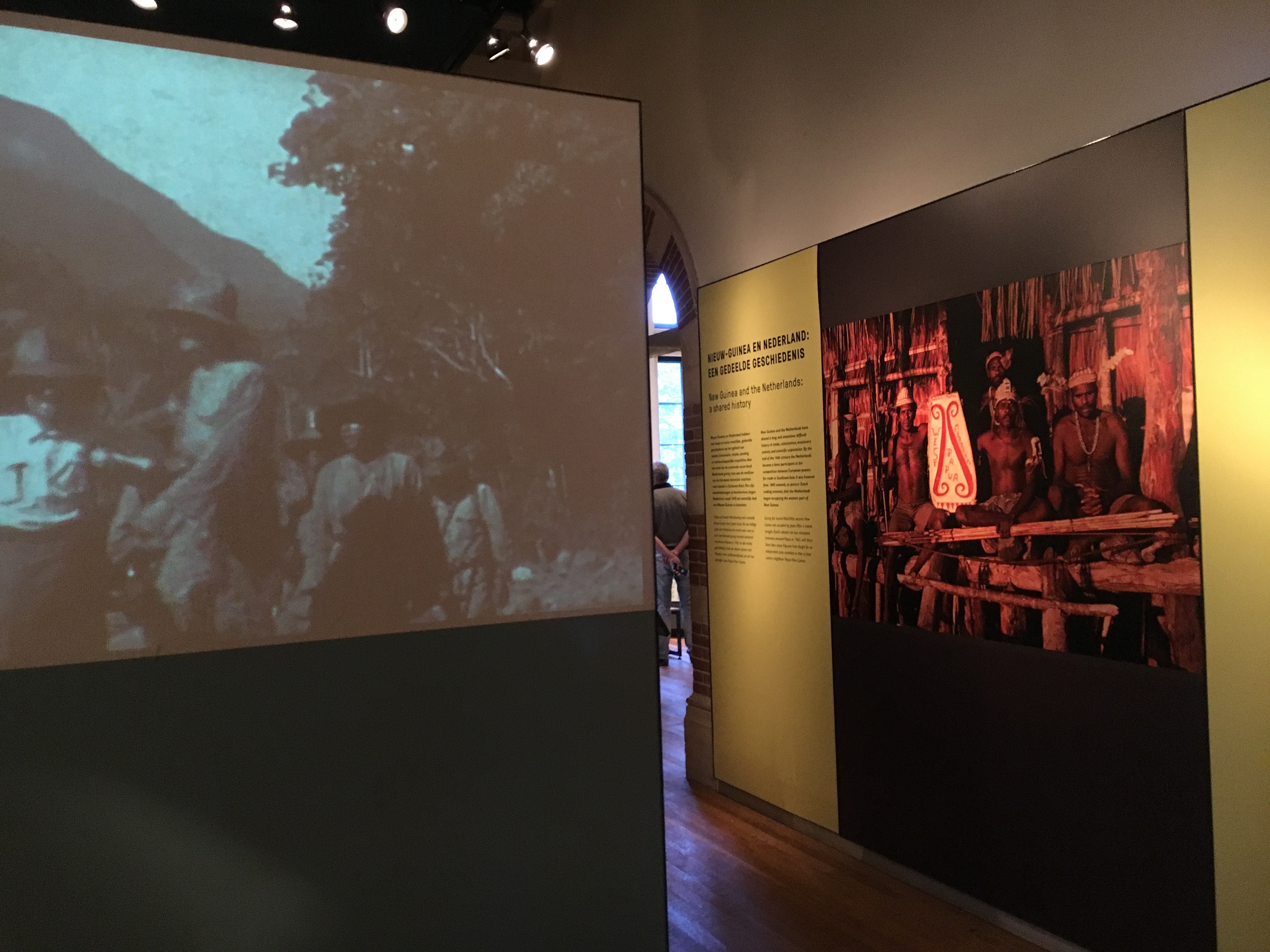

Throughout the Tropenmuseum, photography is consistently framed within a clear theoretical agenda that aims to challenge the representation politics and aesthetics around the tradition of museum collections. Curators counter-position different photographic genres, a strategy that Elizabeth Edwards argues “offers multiple entry points for visitors to engage a range of fluid learning experiences [that] stress subjectivity, critical, or incisive elements in images.”[4] An important section in the Tropenmuseum display, for instance, discusses the Dutch colonial history in New Guinea through short films, dioramas, audio content, chat labels, paintings, historical photographs, and artifacts.

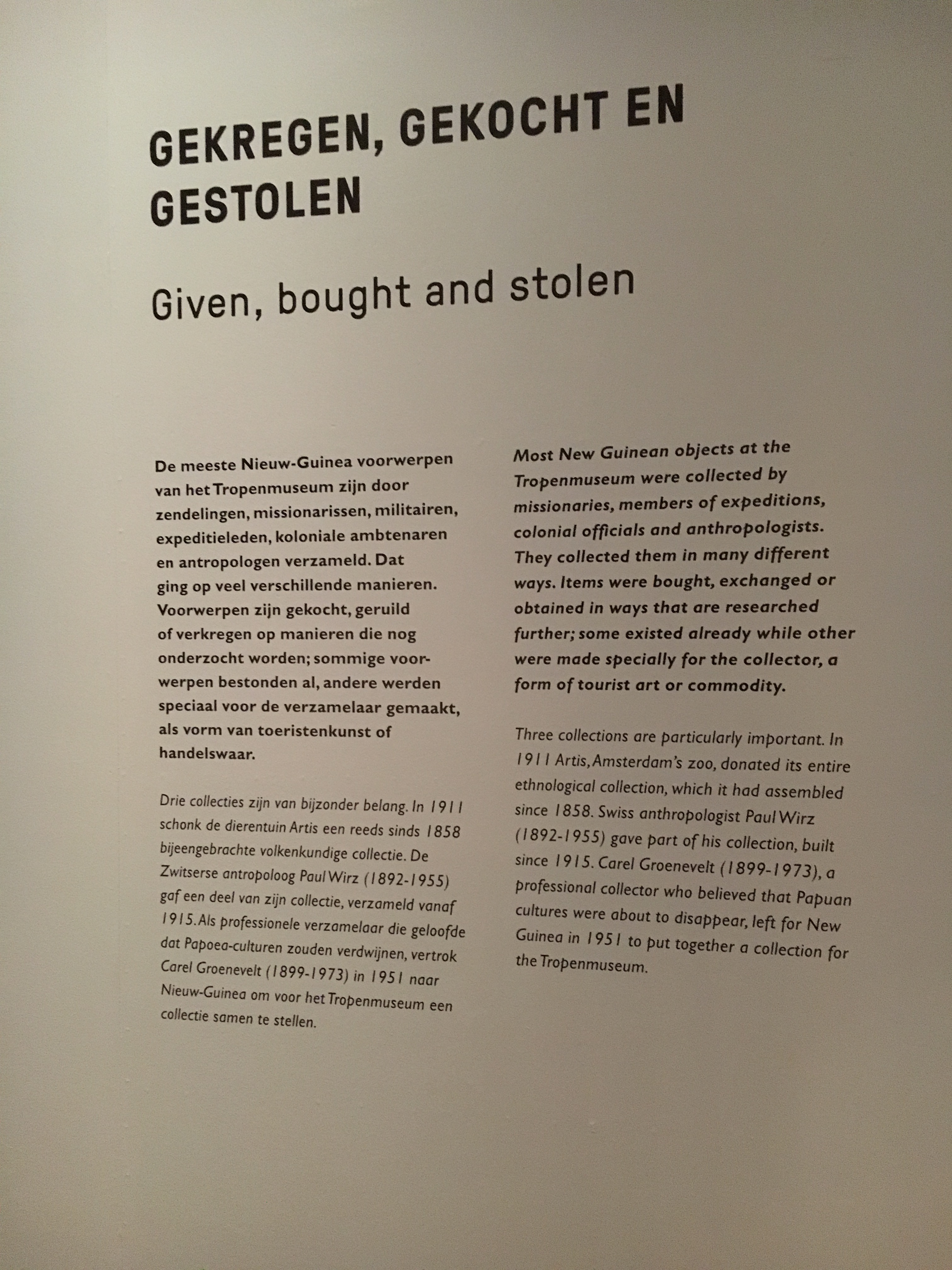

Through these objects and didactics, the gallery space discursively explains the various colonialisms that occurred in the region and the relationship of each with specific museum holdings. For example, the entry’s introduction label presents that which has been “given, bought, and stolen.” It discusses how most of the objects in the collection were collected by missionaries, members of expeditions, colonial officials, and anthropologists. These displays counter-position different kinds of media and invite a variety of viewer responses within the gallery space.

Figure 1. Wall text, “Given, Bought, Stolen” at the Tropenmuseum, Haarlem, the Netherlands. Photo by Marion Cadora.

One of the focal points of the gallery is a diorama that positions viewers such that they are made aware of their own complicities in looking. It focuses on “ethnographies of seeing” rather than ethnographies of content.[5] The display shows a Dutch man pointing his camera lens towards the wall with a black and white photograph of eleven Asmat men posing on a canoe looking towards the viewers. The materiality of the display plays a major role in the way the black and white image is read: it moves away from framing and matting towards a display that reenacts the moment of photographic capture. The display reveals how the camera has historically been used as a “seeing machine” that disciplines bodies in colonial sites and as an “empire’s technology” that produces indexical evidence for the state.[6] The materiality of the display recodes the meaning of the photograph, inviting viewers into the arbitrary nature of representation by showing what exists outside of the photo’s frame.

Figure 2. Ethnographic diorama of photographer and Asmat men at the Tropenmuseum, Haarlem, the Netherlands. Photo by Marion Cadora.

Figure 3. Display of West Papuan men holding a shield adorned with the text, Papua Merdeka/“Freedom for West Papua.” Tropenmuseum, Haarlem, the Netherlands. Photo by Marion Cadora.

Another important image in this gallery shows five West Papuan activists holding an Asmat wooden shield with the phrase Papua Merdeka, which translates to “Freedom for West Papua.” This photograph offers a visual representation of West Papuan activism and importantly takes into account the contemporary geopolitics of New Guinea. The western half of the island of New Guinea, West Papua, was annexed by Indonesia and integrated as a province after a contested referendum of self-determination in 1969.[7] While the Indonesian military has complete control of land resources in the present day, conflict, violence, and exploitation continue to threaten the survival of West Papuan people.[8] The photo plays a crucial role in the gallery, giving museum visitors an example of how photography is used as a potent tool to assert resistance to colonial powers. Visually, it holds a recuperative purpose and inserts stories of resistance that are often dislocated in ethnographic spaces.

Figure 4. Gallery view at the Tropenmuseum, Haarlem, the Netherlands. Photo by Marion Cadora.

Figure 5. Red Calico (Rood Katoen) #2, Roy Villevoye, installation view. Photo by Marion Cadora.

This decision to include images of and references to contemporary geopolitics is particularly poignant at the entrance of the New Guinea art display, which includes objects such as shields, textiles, and body adornments. At first glance, this part of the exhibit maintains conventional modes of display, such as the use of dramatic low lighting, large glass display cases, and organization by object type. This curatorial method is strikingly similar to what James Clifford calls “aesthetic universalism,” a curatorial practice that preserves the central spectacle of the authenticity and purity of objects.[9] However, the aesthetic paradigm is radically transformed with the inclusion of a politically oriented multi-media installation by Dutch artist Roy Villevoye that highlights ongoing struggles for sovereignty in West Papua. Villevoye’s installation, entitled Red Calico (Rood Katoen) #2, shows thirteen mannequins wearing t-shirts (collected by the artist in the 1990s) of various colors that are aged, shredded, torn, and ripped. Hanging on the walls behind the mannequins are large photographic portraits of the wearers posed in defiant stances.

Directly exposing contemporary resistance in West Papua, Villevoye’s installation intervenes in the assumed neutrality of the gallery space. The installation incorporates images of Asmat communities as active political players rather than as primitive or passive objects, or as part of a facile celebration of culture and diversity—as is often the case in exhibitions of New Guinea art. The installation reveals that the t-shirt alterations were a protest against the clothing rules imposed by the occupying Indonesian power. This contemporary installation, along with the information paired with the collection, unsettles the visual force of “aesthetic universalism” and opens a multifocal conversation about the relationship between politics, activism, art, and artifact. The installation prompts museum audiences to consider their own expectations regarding the museum space.

Such examples highlight how colonial photography and heritage in the context of the Tropenmuseum become tools with which to analyze racism and coloniality as it persists in contemporary society. Photography is strategically employed as an interpretive strategy by counterpoising genres and opening up multiple frameworks for visitors to access. By including politically oriented photographs and using photos to intervene in expectations of institutional neutrality, curators destabilize the “truth production” of photographic work and make viewers aware of their own complicities in looking.

Decolonization and Reconciliation

The Tropenmuseum is an example of how colonial media can be reframed to dismantle the myths surrounding the colonial era. These concerns return us to the question posed at the beginning of this essay: is it possible to decolonize a space so intricately tied to colonialism?

In a recent museum studies symposium held at the University of Hawai‘i on the topic of decolonizing museums, the organizers suggested, “If colonialism is the means by which Indigenous lands, bodies, and possessions were appropriated by others for their own use, then ‘decolonization’ has been the process of reversing these acts, politically and culturally, while reconsidering history, agency, and accountability through an Indigenous framework.”[10] Corroborating this idea Amy Lonetree states that a decolonizing museum practice must be in service of speaking the hard truths of colonialism and generating critical awareness about historical trauma in order to heal the unresolved historical grief that continues to harm Native peoples today.[11]

Some scholars, however, have posed challenges to these efforts at institutional decolonization. For example, Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang discuss how decolonization is not the same as mere inclusion or contemporary forms of truth and reconciliation. Rather decolonization, they argue, means only one thing: the repatriation of Indigenous land and life. They call out, for instance, “settler moves to innocence,” whereby the pursuit of critical consciousness among non-Native peoples can turn into “diversions, distractions, which relieve the settler feelings of guilt or responsibility, and conceal the need to give up land, power or privilege.”[12] Importantly, they also distinguish between reconciliation and decolonization. Reconciliation is concerned with rescuing settler normalcy and futures; it centers questions such as what will decolonization look like and what will happen after abolition?[13] According to Tuck and Yang, until stolen land is relinquished, critical consciousness does not automatically or necessarily translate into action that disrupt colonialism.

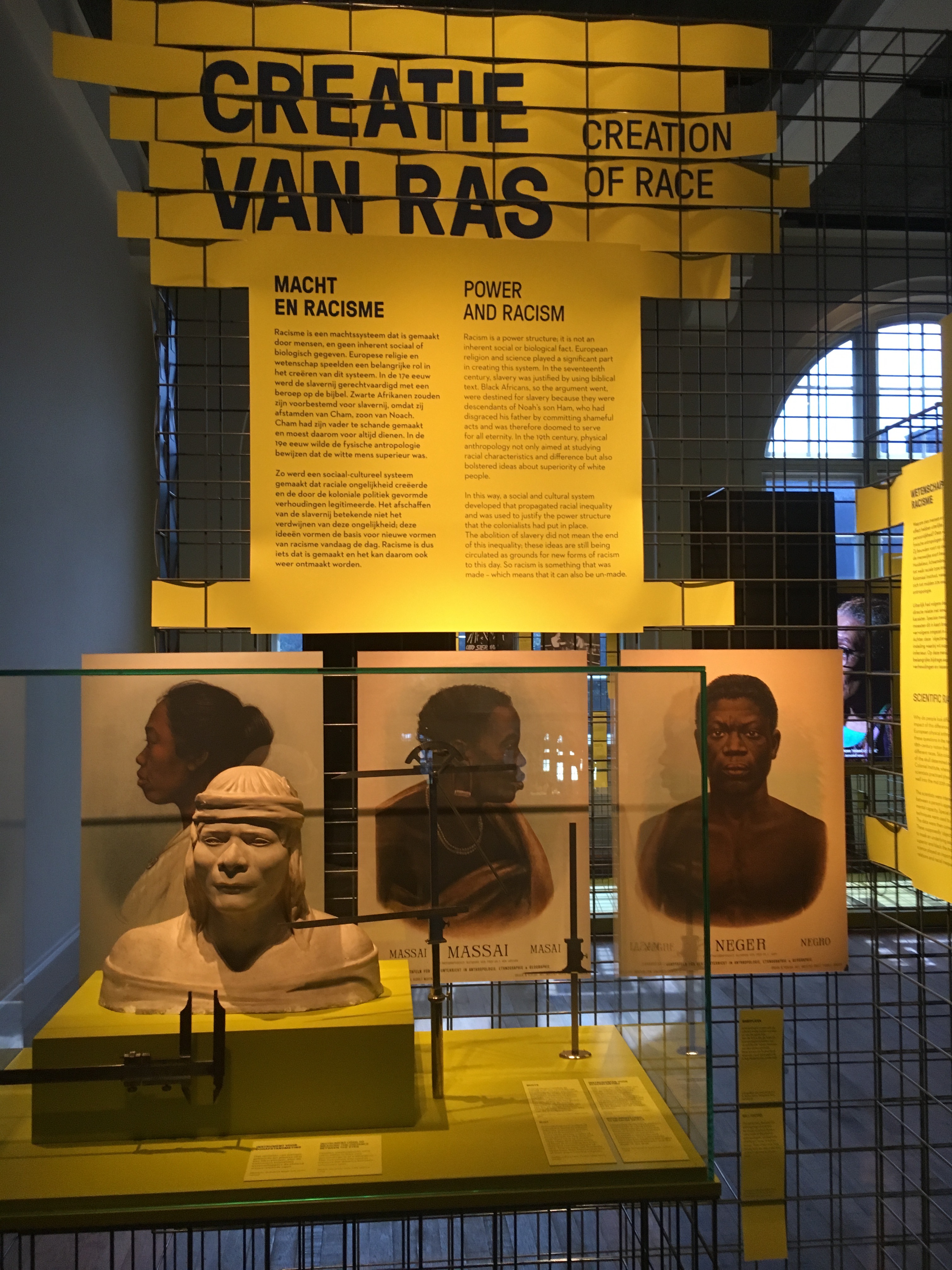

The Tropenmuseum does the important work of opening up critical and politicized conversations around their collections, but as Tuck and Yang suggest, critical discourse is not the same as decolonialization. Their curatorial work more precisely reconciles Dutch viewers to their own colonial histories by revealing how museum collections are complicit in the unequal structures of colonial power. This attempt at reconciliation becomes even more pronounced at the end of the exhibit, in a permanent display entitled Afterlives of Slavery that overtly embeds the objects throughout the museum within the violent histories of racial slavery. It bridges a dialogue between the colonial era and present-day politics by showing the ways in which enslaved people resisted the system, not only by mounting rebellions but also through forms of creative and cultural expression. These latter practices are addressed through contemporary art installations and videos of Dutch poets and spoken word artists. The exhibit ends with a prompt that asks the following question: “What is the price of freedom?” One visitor responded with the following words: “The life you lived before. You must analyze the present, past, and yourself.” This comment shows how Tropenmuseum display creates a space for Dutch viewers to contemplate their own complicity and positionality in ongoing forms of racism and colonialism.

Figure 6. Afterlives of Slavery, installation view at the Tropenmuseum, Haarlem, the Netherlands. Photo by Marion Cadora.

Figure 7. Afterlives of Slavery, installation view at the Tropenmuseum, Haarlem, the Netherlands. Photo by Marion Cadora.

Decolonization in a museum such as the Tropenmuseum would offer something different— a much more unsettling narrative for institutional spaces and perhaps more closely related to ideas presented by West Papuan activist Benny Wenda:

When I speak in museums people always ask me what I think about objects in museums from my country–always the same question! These objects are being kept in museums and they being looked after very nicely, but what about the human beings? You can’t separate the objects from the human beings, because the humans are part of the objects and the objects are part of the people. When the missionaries, anthropologists and all those people came we gave some of our objects to them, but I don’t think they really knew how special some of the objects were. But one day when West Papua is free, I like to think these objects will go back.[14]

Where museums are often more concerned about objects and not necessarily the people or places they come from, Wenda makes a strong case that in the context of West Papua museum objects and human lives cannot be separated. His primary concern is social justice for West Papuans, making the claim that political freedom for West Papuans should include the repatriation of colonial collections. The Afterlives of Slavery and other permanent displays discussed in this article are less about West Papuans or the colonized subject and more about altering a Dutch viewer’s understanding of their own colonial history— one that is more complementary to the traditional role of a museum rather than unsettling to its existence.

Notes

[1] The Tropenmuseum manages a collection of 180,000 objects and 270,000 photographs that was collected during the colonial era.

[2] David van Duuren, Oceania at the Tropenmuseum (Collections at the Tropenmuseum) (Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, 2011), 6.

[3] This information was gathered from a conversation I had with Wony Veys in June, 2018.

[4] Elizabeth Edwards, Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology and Museums (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2001), 206.

[5] Ibid., 196.

[6] Adria L. Imada “The Army Learns to Luau: Imperial Hospitality and Military Photography in Hawai’i,” The Contemporary Pacific 20, no. 2 (2008): 338.

[7] Jason MacLeod, Merdeka and the Morning Star: Civil Resistance in West Papua (St Lucia, AU: University of Queensland Press, 2015), 5.

[8] Ibid., 61.

[9] James Clifford, “Quai Branly in Process,” October, no. 120 (2007): 14.

[10] Museum Consortium, “Seeding Authority: A Symposium on Decolonizing the Museum,” http://www.museum.hawaii.edu/decomu2018/, accessed on October 1, 2019.

[11] Amy Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), 5.

[12] Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 21.

[13] Ibid., 35.

[14] Lissant Bolton et al., Melanesia: Art and Encounter (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2013), 1–59.

Marion Cadora is a Visual Studies PhD student at University of California, Santa Cruz with a focus on critical curatorial practices and art of Oceania. Previously, Marion worked as a curator and educator at various institutions including University of Hawai‘i, Mānoa, University of Goroka (Papua New Guinea), and the de Young Museum of San Francisco.