Navigating the Virtual Labyrinth: An Exploration of the Winchester Mystery House as a Digital Ghost

Thursday, December 14, 2023 at 6:32PM

Thursday, December 14, 2023 at 6:32PM Allison L. Farrell

[ PDF Version ]

When the COVID pandemic stopped the world in its tracks, many museums began to find alternative methods of providing the public with the experience of their exhibitions. The Winchester Mystery House, formerly known as Llanada Villa and home of the eccentric firearms heiress Sarah Lockwood Pardee Winchester, is no exception. Physically located in San Jose, California, the Mystery House now also exists online as an Immersive 360° Walkthrough, a 3D tour and virtual reality (VR) experience. Guests, for a small fee, are now able to roam through the supposedly haunted labyrinth of hallways, lavish interior design, and odd architectural details while learning more about Sarah and the house’s history through informational pop-ups. The house is empty in these tours with the rooms (mostly) open for guests to float in and out with uncannily smooth motions. The 360° Walkthrough, a product of Matterport, also provides those who tour the digital house with the ability to choose precise locations and “teleport” to nearly any spot in the four-story building, its basement, and the surrounding greenspace.[1]

While this self-guided 3D tour is an understandable replacement for an in-person experience during a pandemic, interaction with the Mystery House in virtual reality becomes something new and different within the context of the house’s reputation. There are spectatorial gaps in understanding the context and purpose for visiting the Mystery House outside of its physical space. Due to the constraints of not being within a physical space, the Mystery House’s 3D tour appears to deprive visitors of the context in favor of the general representational experience. However, there is also the potential to experience the house as something else entirely—a guest becomes a ghost wandering the empty halls. Yet, it is divorced from the in-person phenomenological experience in favor of a more disconnected, noncorporeal mode of viewing. Drawing upon concepts such as Walter Benjamin’s aura, Richard Grusin’s radical mediation, and Amy J. Lueck’s considerations of the body and its relationship to space and public memory, I argue that one can understand the Walkthrough as a space separate from the house itself, with the same façade and traces of the house’s history. Through the unique experience that the 3D tour offers while seeing the Mystery House in this frozen and uncanny state, there is potential to redefine what it means to encounter a haunted space, even if the virtual house is the ghost of the original. In doing so, I argue that the experience of a noncorporeal body within a digital space possesses a mutuality with the mediated presence of a specter in a physical space.

The primary draw for visitors of the Mystery House is its proximity to a sense of darkness alongside the strangeness of the house’s aesthetics. For Benjamin, the aura is in part the “unique apparition of a distance.”[2] The interaction with and/or participation in this virtual reality lends itself to allowing for some experience of the original house’s uniqueness and legendary status, with its cultural and historical context being beyond a mere ghost story. The “ominous distance” of an aura, as Miriam Hansen says, plays into how we encounter the house’s atmosphere in physical space; rather than wandering just another house, visitors see “a past whose ghostly apparition projects into the present.”[3] Sarah Winchester funded the construction of Llanada Villa from the inheritance given to her by her late husband, William Wirt Winchester. William Winchester’s ownership of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company profited directly from colonial Westward Expansion as well as the Civil War through its progenitor, the New Haven Arms Company’s rifle featuring the deadly .44 Henry round.[4] According to legend, when Sarah Winchester faced the destruction that Winchester Arms profited from during the Civil War, her guilt consumed her to the point of perpetually adding on to her house as a means of confusing the spirits of Winchester rifle victims who sought vengeance. Moreover, she was believed in some yellow journalist papers to be a practicing Spiritualist, allegedly performing séances in the oddly-peaked room in the South Turret referred to as the “Witches’ Cap.” I build upon this narrative in comparison to Benjamin’s more abstract attributes of the aura to understand how the Mystery House can be seen in the context of a museum and historic site, a haunted space that is plagued by much more than a ghost. Traces of a history of war, death, guilt, and natural disaster are present to many guests as soon as they physically enter the front door of the Winchester Mystery House.

The atmosphere of the Mystery house is something that draws its tourists in, where history and storytelling overwhelmingly influence the guided tour. Lueck notes that she experienced a sudden realization of scale in the guided tour with an oddly small door, one that is allegedly the same size as Sarah herself, which then established for her a “sense of unsettling contrast for the visitor and a sense of strangeness in both the woman and the house that is pursued throughout.”[5] The Mystery House’s overall Victorian style allows those who experience it in physical space to place it into the context of the world outside its gates of entry. At the same time, the house's surreal aura creates a distance between it and its guests; Sarah's influence and the strange legends associated with her are mediated through that sense of wonder and alienation. As Lueck describes: “Each speculative claim makes the same move: shoring up the aura of mystery, while deflecting from the fact that the tour is, in fact, constructed largely around conjecture and supposition rather than material or textual evidence. ‘Honestly, we don’t know what Winchester was going to do because she was so strange.’”[6] Guests at the physical house are “invited throughout [the tour] to conflate the house with the woman herself,” which we also see with the virtual tour’s fascination with the house’s anomalies.[7]

The space’s surreal atmosphere lends itself to the onlooker’s feelings of awe and curiosity that drive interest in the house. The Mystery House is an example of what Bachelard calls a “house of wind and voice,” a space that “hovers on the frontier between reality and unreality.”[8] In virtual reality, some glitches and strangeness are to be expected, but it is fascinating how the stylistic choices and post-earthquake architectural quirks leave the observer feeling as if they are looking at something created in a dream, or is corrupted by having too many reminders of the house’s past in view. As Bachelard notes the surreal quality of “the house” in the sense of its ability to invoke psychological associations, Ignoffo explains how the earliest reports describe Llanada Villa as a fantasy space: “You mechanically rub your eyes to assure yourself that the number of turrets is not an illusion, because they are so fantastic and dreamlike. As you approach nearer, others and many others are still revealed in a bewildering spectacle.”[9] As surreal art is meant to invoke the world of dreams, a wandering guest becomes one step out of reality. The physical house, with its bizarre layout, is steeped in unreality: with its weblike maze of rooms, puzzling switchback stairs, and odd placements of doors and windows, the outside of the house is fantasy with the inside appearing to follow a dreamlike logic in its design.[10]

Figure 1. Window on Floor.

The 1906 earthquake decimated certain architectural elements that created a surreal layout, yet the experience of the house still heavily emphasizes the mysteriousness of this space.[11] Some rooms are left completely empty while others are furnished in period-appropriate (though not original) furniture, suggesting a lack of knowledge of the entire purpose of the house due to the layers of mythology that have been attached to it.

For the haunted element of the Mystery House, it is the spectral body of Sarah Winchester and her staff that tend to loom over tours of the house, with the more ominous and distant spirits of Winchester rifle victims buried beneath and kept within the tours’ narratives. Historical context has been added and removed as needed to bolster an aura of ghostly mystery, as some rooms echo with emptiness and a select few given the sense of being a home; this distances the guest from seeing the house as the dwelling space of a woman and instead becomes something of a cipher. In the construction of Sarah Winchester as the historical anchor of the house, we see how, to quote Lueck, “particularly for women, who are traditionally associated with domestic spaces, … the interplay between the space and embodied or imagined personhood” builds her ethos as a legendary figure and allows those inside the Mystery House to let themselves become lost in the house’s stories.[12] There is the issue of Sarah’s absence, however, especially when we consider the porous nature of fact and fiction when it comes to her story. To quote Bachelard again, without the context of Sarah herself in the physical and digital home and the mystery created by scant historical evidence of her true intentions, the old house becomes a “geometry of echoes,” where “the voices of the past do not sound the same” from room to room.[13] This unreal environment is the result of the Mystery House being very deeply set within its own history, folklore, and overall sense of place. It is a “site of memory” that has proven to be highly suggestable to the perceptions of outsiders.[14]

The house is marked by distance: the distance from one end of the house to the other, the century between the visitor and Sarah, and above all the distance between the living and the dead. Its qualities as a museum create distance from its original role as a home, with its aura growing to fit the new definition of the space. With each iteration of the house from simple home to mansion, ruin, restoration, museum, and finally digital reconstruction, there is a “decay of the aura” in the sense that through reproduction, the aura “withers."[15] The aura, “a strange tissue of space and time,” provides the viewer with an understanding of an object’s uniqueness; the decay of the aura, then, stems from the present-day desire to annihilate the distance between viewer and object or by “assimilating” it as a reproduction.[16] When considering the Mystery House, the tissue of the aura is stretched out, a membrane of spacetime unraveling everywhere one steps. Its reproduction, which allows the spectator to experience the uniqueness of a place, is then found in its virtual tour.

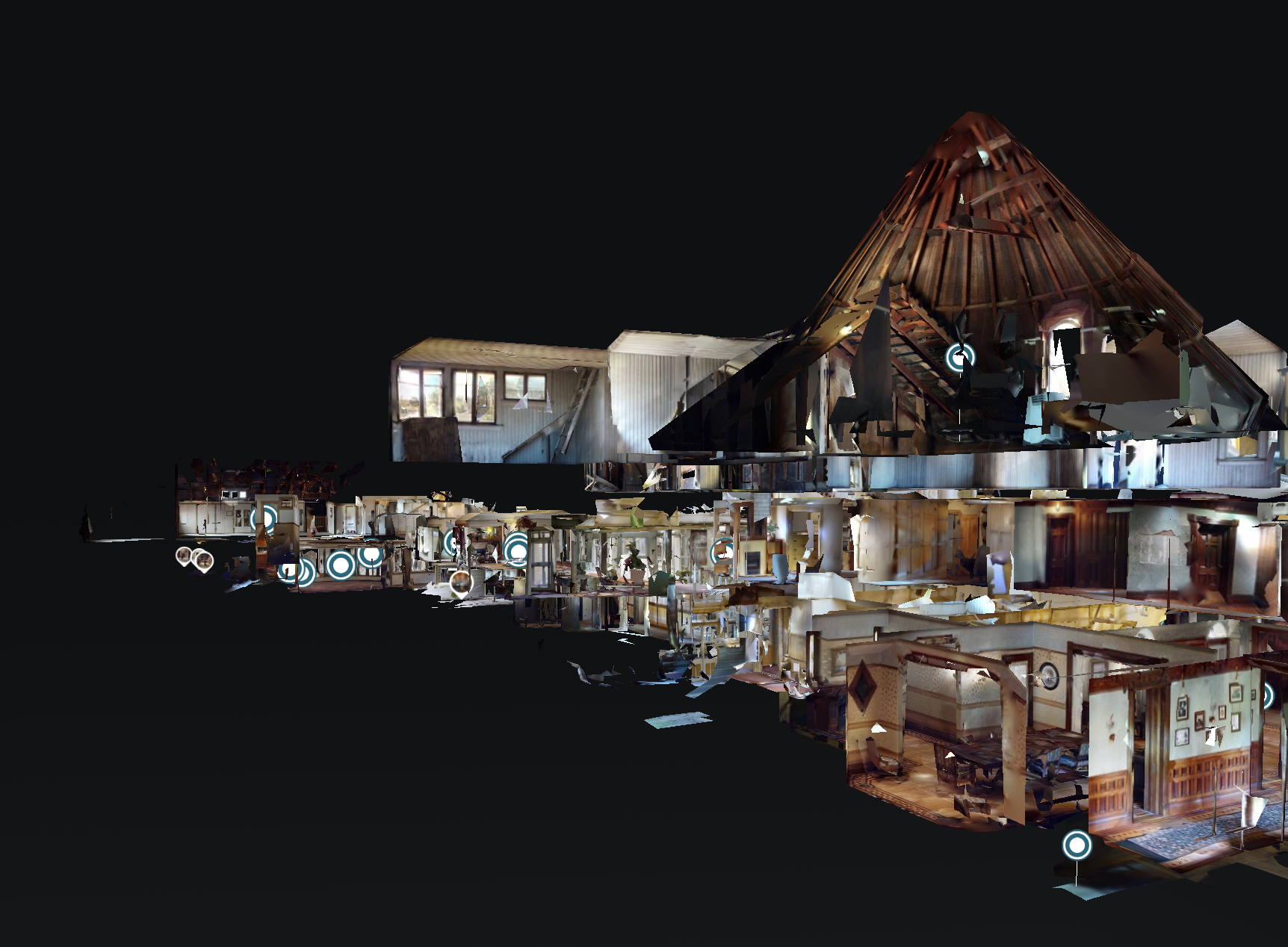

For the 3D tour, there are reminders of scale and references to history, but these experiences are found in corners and through methods that are unique to the digital space. The “Dollhouse” setting, which provides a semi-transparent view of the entire house from an overhead view, provides the viewer with a sense of scale, but entering through the carriage house does not connect one with the small door, making the physical experience null and void to the virtual guest. Likewise, movement through the house is something that is unrestrained by a guide or human feet, with the ability to become lost even easier for the virtual guest, at the cost of being able to do things such as enter specific rooms or even look up at the high ceiling of the Witches’ Cap, despite its architectural and mythological appeal. While the house is still architecturally fascinating with many beautiful rooms, there is a definite understanding that one’s experience is something that is distinctly not the Winchester Mystery House of San Jose, California, the former home of Sarah Winchester. The aura of the Mystery House is destroyed in its digital recreation, but a new aura, one specific to the digital place, is created. To consider this further, we must delve into the virtual labyrinth and examine how we experience floating through its digital walls.

“In even the most perfect reproduction,” Benjamin states, “one thing is lacking: the here and now of the work of art—its unique existence in a particular place.”[17] With a reproduction frozen in time, a permanent digital stasis, there is a sense of experiencing a facsimile that not only draws attention toward what is lost in the reproduction, but also takes away from the auratic experience of the original, for better or worse. This tension can be addressed through alternative forms of mediation. As defined by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, remediation consists of “import[ing] earlier media into a digital space in order to critique and refashion them.”[18] In the case of the Mystery House, refashioning is shown through the high-quality imagery and generally user-friendly controls for the computer; the goal, above all, is to make the tour “immersive.” This immersion, however, is somewhat interrupted by the “Dollhouse” setting of the 3D tour, in which the digital space becomes compressed and even nightmarish when interacted with improperly, through strange movement or extreme choices of perspective when looking at the house skinned of its exterior walls.[19]

Figure 2. Dollhouse.

With the Mystery House’s reproduction in this 3D iteration, the digital model then becomes a production in and of itself and facilitates its own experience.

The house is frozen in time and space. The sun is forever bright, suggesting a mid-afternoon summer day in Northern California. The house is deserted and completely silent, save for the occasional video that is included as an informative supplement. Approaching a mirror is an eerie experience, as there is no reflection, and it is difficult to actually face one with the controls. The most noticeable variation from the physical experience, though, is movement. With keyboard controls, the spectator glides through the house, stopping at predetermined locations marked with circles or soaring down the hallways faster than even running speed. Word bubbles provide information, but otherwise there is a lack of context without a guide. While Matterport, in designing this virtual space, uses similar methods in real estate virtual tours via maneuvers from arrow keys and clicks, the sheer size of the house and sense of being in a historically significant or even sinister space begins to give the impression of the atmosphere and embodied experience of being in a horror movie.[20] It is easy to get lost, and there are glitches in the program that lead to some truly bizarre experiences.

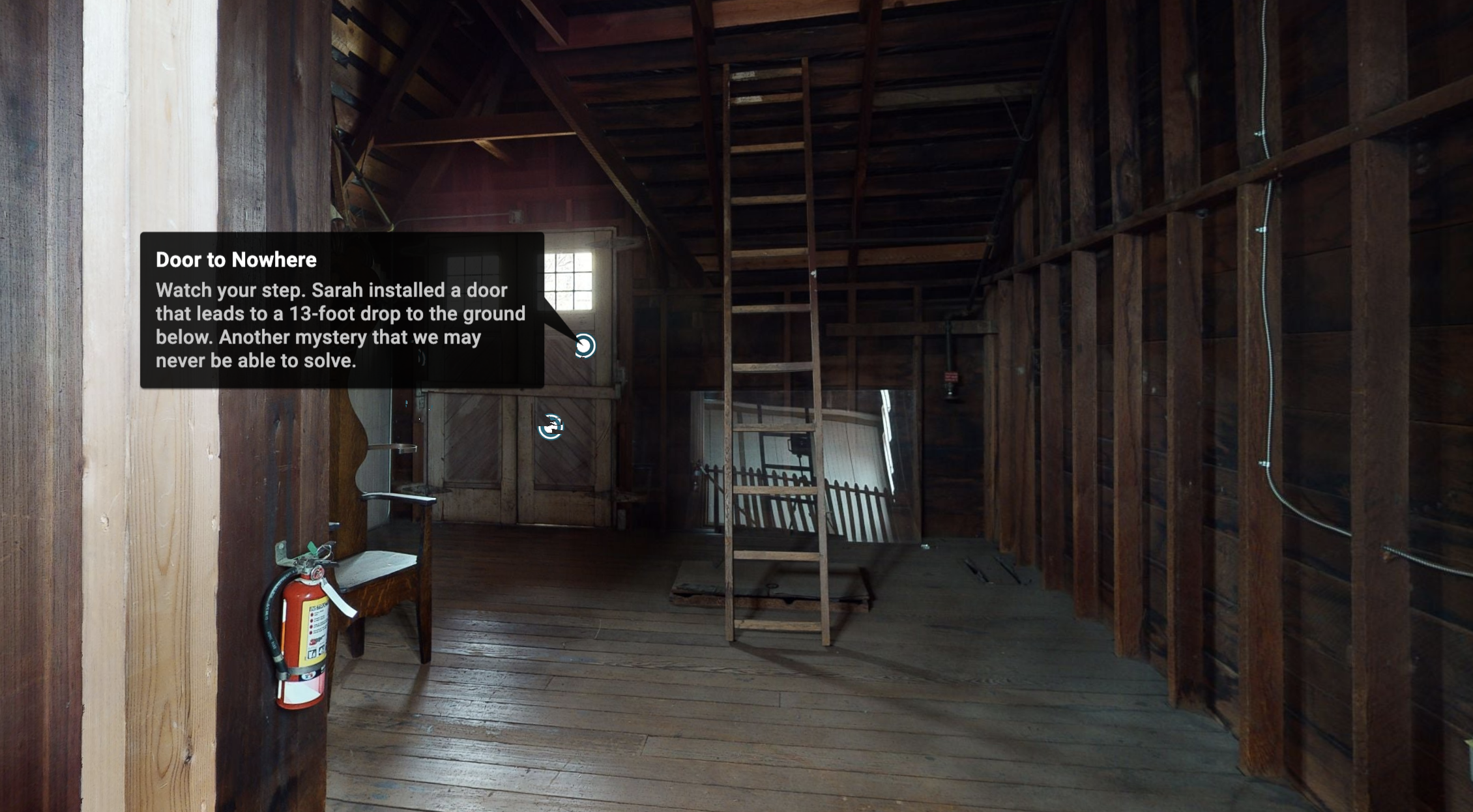

Take, for example, the “Door to Nowhere.” Not far from Sarah’s room, there is a loft with a door that opens to a sheer drop to the ground at the physical house. However, in a digital environment, a glitch in the program where two checkpoints align in such a way that they have been unintentionally connected, which causes the viewer to fly through the “Door to Nowhere.”[21]

Figure 3. Door to Nowhere.

A nightmarish smear of colors and lateral movement brings the guest to a room at the opposite side of the house, at the highest point of the Mystery House. The Door to Nowhere becomes a portal. At other times, one can phase through walls, with a stray click leading to an adjacent room without quite knowing how to return. By design, employee-only spaces and storage closets are off-limits, with one’s noncorporeal “body” being nudged beyond what the guest intended. We are thus given new affordances and constraints within the medium of virtual reality when interacting with the 3D tour instead of the house in San Jose in physical space with corporeal bodies. Our digital bodies, or “avatars” according to Legacy Russell, have experiences that are “prosthetic” to our physical bodies and “recognize that the skin of the digital transforms and is transformative.”[22] Our avatars then respond to glitches or “breaks and system failures” in such ways that “we find new beginnings.”[23] These movements evoke the feeling of having a ghostly presence, but the viewer is very much alive; it is the atmosphere of the place itself that makes us more aware of our presence in virtual reality and creates hauntings. The body possesses the weightlessness and extradimensional movement of a spectral body while being bound to the limitations and glitches of a digital one.

In “Radical Mediation,” Richard Grusin argues that technology operates to “…function technically, bodily, and materially to generate and modulate individual and collective affective moods or structures of feeling among assemblages of humans and nonhumans.”[24] Considering this notion of radical mediation as something that is “affective and experiential,” not “strictly visual,” we can understand the Immersive 360° Walkthrough as being an experience involving not only our physical bodies, navigating the 3D tour through our keyboard controls, but also as noncorporeal, digital bodies, floating aimlessly through the virtual house.[25] Bolter and Grusin observe in Remediation that “…like other media, virtual reality can provide its own, self-authenticating experience… by remediating other point-of-view technologies and especially film.”[26] The wavering line between human experience of physical and virtual reality is the conduit of mediation. It is the “embodied immediacy” of simultaneously experiencing being in these two “bodies”—the physical body and the presumed, ghostly, digital body—at once, with the guest’s experience transforming and taking on new adaptations with these mechanics.[27] Considering the Mystery House once again as a house, it is the extension of Sarah Winchester’s legacy because, Lueck says, “women’s ethos has been inextricably linked with the places they occupy” and therefore “Winchester comes to be haunted by her house,” as are we, just as “she haunts it.”[28] A virtual Mystery House is an entity in and of itself, with its own ghosts.

The question visitors are welcomed to ask is, then: is the Winchester Mystery House haunted? The answer, as far as public memory and folklore are concerned, is yes; even for the skeptic of the paranormal, it is undeniable that the Mystery House is frequented by traces of history and uncertainty in context related to its enigmatic creator. More importantly for this discussion, is the 360° Walkthrough haunted? If so, haunted by the ghosts of what? The viewer, though ghostly in their movements around the house, seems to be the only living being in this space, and they presumably enter with a sense of curiosity and anticipation, but not with traces that imprint themselves on the 3D tour itself. It is our visitation of the virtual haunted house as guests and spirits that, through this analysis, allows us to pull back the veil of remediation between these interpretations of the Mystery House. Using the experience of navigating this space through the invisible, digital body as opposed to one’s physical presence in the house, we can observe that the virtual house is also haunted by the “real” house, and vice versa. The experience of being in the space, however, exists beyond the capability of the physical body in this space, with the ability to teleport, phase through walls, and fly down hallways stymied by a closed door or the presence of a mirror.

In the case of enigmatic spaces such as the Winchester Mystery House, which relies on its specific ambiance to create and define an experience, a change in media leads to an almost complete destruction of its aura. Within the confines of a digital space such as the 3D tour, however, there are still references to its historical context, its atmosphere, and it being a palimpsest of the lives the original house has lived. The house, once reproduced as a virtual space, can be explored by a virtual body. A ghostly, labyrinthine mansion becomes a facsimile, only to regain its atmosphere through its unique viewing experiences and idiosyncratic glitches. These constant processes of mediation and remediation are reliant on their relation to the body and space, existing in mutuality with their digital, or supernatural, doppelgängers.

Notes

[1] Matterport is a software company best known for their 3D modeling of spaces and the creation of “digital twins” via virtual reality. Matterport is also responsible for the 3D tours of popular real estate website Zillow, hence why one may be familiar with these controls in the unfamiliar environment of the Mystery House.

[2] Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility: Second Version,” in The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), 23.

[3] Miriam Hansen, “Aura: An Appropriation of a Concept,” in Cinema and Experience: Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor W. Adorno. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 107.

[4] “The Complete History of Winchester Repeating Arms,” Winchester Repeating Arms, https://www.winchesterguns.com/news/historical-timeline.html, accessed Oct. 2023; The Henry rifle was produced by the New Haven Arms Company for the war, though its creator, Benjamin Tyler Henry, went on to work on designing firearms with Oliver Fisher Winchester and Daniel B. Wesson.

[5] Amy J. Lueck, “Haunting Women’s Public Memory: Ethos, Space, and Gender in the Winchester Mystery House.” Rhetoric Review 40, no. 2 (27 May 2021): 111.

[6] Lueck, “Haunting Women’s Public Memory,” 113.

[7] Lueck, “Haunting Women’s Public Memory,” 114–115.

[8] Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas. (New York: Penguin Books, 2014), 80.

[9] From the San Jose Evening News, 29 March 1895, cited by Mary Jo Ignoffo, Captive of the Labyrinth: Sarah L. Winchester, Heiress to the Rifle Fortune (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2010), 139.

[10] An example of dreamlike design choices not caused by the earthquake: this conservatory inexplicably has a window on the floor.

[11] Ignoffo, Captive of the Labyrinth, 113.

[12] Lueck, “Haunting Women’s Public Memory,” 116.

[13] Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, 81.

[14] Lueck, “Haunting Women’s Public Memory,” 108.

[15] Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility,” 22.

[16] Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility,” 23.

[17] Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility,” 21.

[18] Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, “Mediation and Remediation,” in Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), 53.

[19] Above is the “Dollhouse” view, featuring full height of Witches’ Cap.

[20] The sense of being in a horror movie is fitting, as the house is the setting of Winchester (dir. Michael Spiering, Peter Spiering, 2018), a film inspired by the legend of Sarah Winchester in popular culture.

[21] The “Door to Nowhere” has the landing point of the glitch (white circle checkpoints) partially obscured. This particular glitch point has since been covered by a 360° tour within the 3D tour, though this “Door to Nowhere” glitch is still possible by “jumping” off balconies such as the landing point of this one. URL: https://360tourwmh.com/

[22] Legacy Russell, “Glitch Survives,” in Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. (Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2020), 148.

[23] Legacy Russell, “Glitch is Skin,” in Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. (Brooklyn, NY: Verso), 2020, 102.

[24] Richard Grusin, “Radical Mediation,” Critical Inquiry 42 (Autumn 2015): 125.

[25] Richard Grusin, “Radical Mediation,” 132.

[26] Bolter and Grusin, “Virtual Reality,” in Remediation, 165.

[27] Bolter and Grusin, “Mediation and Remediation,” in Remediation, 132.

[28] Lueck, “Haunting Women’s Public Memory,” 117.

Allison Farrell is a PhD student at the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee. As part of the English department’s Media, Cinema, and Digital Studies program, her research focuses on Media History, Historiography, and Hauntology. She is also co-chair of UWM’s Moving Image Society and a Graduate Teaching Assistant of English Composition.

Reader Comments