Chan Is Missing: Hong Kong Creatives in China’s Orbit

by Michael Curtin

[ PDF version ]

Peter Ho-Sun Chan at the 45th Golden Horse Awards, 2008. Source: Sulekha.com

Peter Ho-Sun Chan is one of the most successful directors in the Chinese film industry, but, unlike his counterparts in Hollywood or Mumbai, he is still looking for a home. Chan was born in Hong Kong in 1962, lived in Thailand as a teenager, and attended the University of Southern California as an undergraduate. He started working in the movie business during the 1980s, first in marketing and then as an assistant director, apprenticed to some of the leading lights of Hong Kong’s golden age, including Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, and John Woo. During the early 1990s, when Peter got his first chance to helm a feature film, he revealed a deft touch with urban melodramas, churning out a highly successful string of movies aimed at young adults (Comrades, 1996; Age of Miracles, 1996; He’s a Woman, She’s a Man, 1994). At that time, the Hong Kong industry was booming, but its success was tinged with anxiety about the upcoming handover of the territory to the People’s Republic of China. “People who could emigrate would do so,” recalls Chan. “There was a feeling that you should make as much money as you could prior to the handover since everything after that would be a big question mark.”[i]

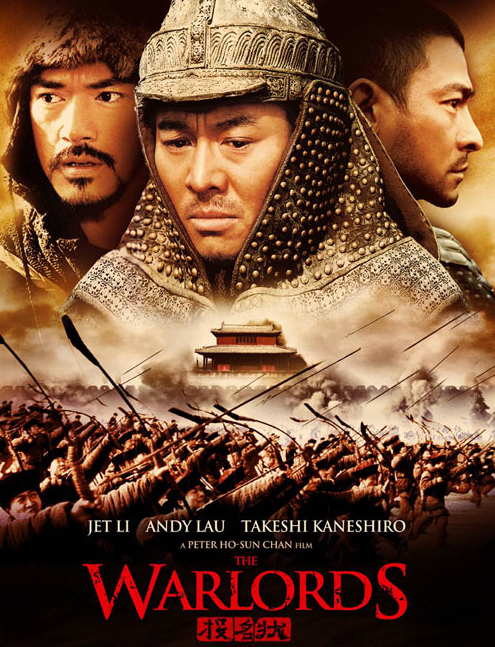

Chan, like many of his peers, began looking for other options and he has been on the move ever since. He took a shot at Hollywood in 1999, where he directed The Love Letter for Dreamworks, starring Kate Capshaw and Tom Selleck. Uncomfortable with Tinseltown corporate protocols, he then started his own Asian distribution company and took a turn at regional coproductions, working with filmmakers in Thailand and Korea. Most recently, and most reluctantly it seems, he has developed coproductions targeted at mainland China (e.g., The Warlords, 2007), a market that now figures prominently in the calculations of most Hong Kong filmmakers. Yet such ventures are fraught with challenges that include censorship, cronyism, piracy, and a general lack of financial transparency.[ii] Many filmmakers have complained about these problems and yet the People’s Republic of China looms ever larger in their calculations, engendering a significant shift in the geography of Chinese-language cinema.

Warlords (dir. Peter Chan, 2007)

Peter Chan claims that today the shrewdest strategy for a Chinese director is to pursue an artistic vision without allegiance to any particular audience or locale.[iii] That’s a big change from the late decades of the twentieth century, when Hong Kong was the center of the Chinese commercial movie business and filmmakers consciously fashioned their products primarily for the local audience. Indeed, the city was then renowned for midnight premiers, where cast and crew would mingle among the moviegoers, taking the pulse of the audience and sometimes adapting the final cut accordingly. Movies were made for locals and their response in turn acted as a rough predictor of overseas success, largely because the city was regarded as a cultural tastemaker. Hong Kong was, moreover, a magnet for creative talent from the far reaches of Greater China and the epicenter celebrity culture. Aspiring talent saw Hong Kong as the most promising place to build a career and Chinese movie executives saw it as the best place to raise financing, recruit labor, and launch projects.

My recent research attempts to capture this spatial dynamic through the analysis of “media capital,” a concept that at once directs attention to the leading status of particular cities and to the transnational regimes of accumulation that promote the concentration of resources in specific locales.[iv] Media capitals are powerful geographic centers that tap human, creative, and financial resources within their spheres of circulation in order to fashion products that serve the distinctive needs of their audiences. Their influence is dependent upon their ability to monitor and discern the imaginary worlds of their audiences and to gather and operationalize resources within their cultural domain. A media capital’s success is therefore relational and its preeminence is subject to competition from other cities that aspire to capital status. Dubai, for example, is self-consciously attempting to challenge the leadership of Beirut within the sphere of Arab satellite television and Miami has recently arisen as a transnational competitor to Mexico City. Media capital encourages a spatial examination of the shifting contours of production and distribution, which both shape and are shaped by the imaginary worlds of audiences. Such research seeks to understand why some locales become centers of media activity and to discern their relations to other locales. Media capitals emerge out of a complex play of historical forces and are therefore contingently produced within a crucible of transnational competition. Those cities that rise to prominence exhibit a shared set of characteristics with respect to institutional structure, creative capacity, and regulatory policy.

Institutionally, media capitals tend to flourish where companies show a resolute fixation on the tastes and desires of audiences. In order to cater to such tastes, they adopt and adapt cultural influences from near and far, resulting in hybrid styles and aesthetics. Such eclecticism and volatility is moderated by star and genre systems of production and promotion that help to make texts intelligible and attractive to diverse audiences. The bottom line for successful firms is always popularity and profitability. Although often criticized for pandering to the lowest common denominator, commercial film and TV studios are relentlessly innovative, as they avidly pursue the shifting nuances of fashion and pleasure. Profitability is derived from structured creativity that feeds expansive (and expanding) distribution systems. Such systems integrate marketing considerations into the conceptual stages of development and financing. Media capitals therefore emerge where regimes of accumulation are purposefully articulated to the protean logics of popular taste.

Just as importantly, media capital tends to thrive in cities that foster creative endeavor, making them attractive destinations for aspiring talent. The research literature on industrial clustering shows that creative laborers tend to migrate to places where they can land jobs that allow them to learn from peers and mentors, as well as from training programs that are sponsored by resident craft organizations. Job mobility and intra-industry exchanges further facilitate the dissemination of skills, knowledge, and innovations. Thus a culture of mutual learning becomes institutionalized, helping to foster the reproduction and enhancement of creative labor.[v] Workers are also inclined to gravitate to places that are renowned for cultural openness and diversity.[vi] It’s remarkable, for example, that the most successful media capitals are usually port cities with long histories of transnational cultural engagement. It’s also noteworthy that national political capitals tend not to emerge as media capitals, largely because modern governments seem incapable of resisting the temptation to tamper with independent media institutions. Consequently, media capitals tend to flourish at arm’s length from the centers of state power, favoring cities that are in many cases disdained by political and cultural elites (e.g., Los Angeles, Mumbai, and Beirut). Successful media enterprises tend to resist censorship and clientelism, and are moreover suspicious of the state’s tendency to promote an official and usually ossified version of culture. Instead, these enterprises absorb and refashion indigenous and traditional cultural resources while also incorporating foreign innovations that may offer advantages in the market, even though such appropriations tend to invite criticism from state officials and high-culture critics. The resulting mélange is emblematic of the contradictory pressures engendered by global modernity, at once dynamic and seemingly capricious yet also shrewdly strategic. Their choice of location is no less calculated: media capital tends to accumulate in cities that are relatively stable, quite simply because entrepreneurs will only invest in studio construction and distribution infrastructure where they can operate without interference over the long term.

The conditions of media capital are dependent on converging forces and therefore subject to the vicissitudes of history. In 1997, when the People’s Republic of China reclaimed Hong Kong after more than a century of British colonial rule, the movie industry was abuzz with speculation about the handover’s impact on “Hollywood East.” The terms of transfer provided a fifty-year transition period in which the city would operate as a relatively autonomous Special Administrative Region, but it was clear that Beijing intended to exert its authority and many believed it likely that government scrutiny of the media industries would increase significantly. This posed a problem for Hong Kong film and TV companies that were accustomed to producing satirical and ribald comedies, as well as fantasy, horror, and crime stories. The city’s creative class grew nervous as the deadline for transition approached, for the very genres that had proven most prosperous were likely to become targets of censors and propaganda officials. Consequently, many producers, directors, and actors began to explore job options abroad and even those that remained in place quietly began moving resources and families overseas in case of an official crackdown. The industry also entered into a cycle of hyperproduction, spewing out as many movies and television series as possible, hoping to generate maximum revenues before the fateful moment of transition. This flooded the market with low-grade products that alienated loyal audiences both at home and abroad. Hong Kong’s reputation—its cultural capital—suffered tremendously as a result. No longer willing to risk the cost of a movie ticket or home video, consumers bought pirated versions that sold for only a fraction of retail price. As audiences turned a cold shoulder to the industry, so too did media professionals in other parts of Asia. Distributors stopped buying, producers stopped collaborating, and directors declined to take Hong Kong talent onto their projects. In the decade following the handover, the industry’s transnational network of audiences, distributors, and creative talent slowly dissolved.[vii]

In retrospect, anxieties about the handover to Chinese sovereignty were somewhat exaggerated, but the effects on Hong Kong’s reputation and its productive capacity were profound. Movie and television companies started shuttering their operations; support services evaporated; and talent dispersed. To make matters worse, government policy regarding censorship remained cloudy, so that many producers urged caution with respect to content issues, fostering a culture of self-censorship that further alienated audiences, especially those in important export markets such as Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia. As the irreverent and innovative qualities of Hong Kong media products diminished, overseas revenues declined and producers were confronted with two options: focus on the tiny domestic market of the SAR itself or enter into projects (often coproductions) with mainland media partners. The former would entail significant downsizing while the latter would require products that were fashioned as much for censors as audiences. The Beijing government also sent signals that it would brook no challenges to the supremacy of state institutions like China Film and CCTV. If Hong Kong firms were to participate in the rapidly growing mainland media economy, they would do so within parameters established by the Communist Party. State policy has gone through many twists and turns since 1997. At times Beijing has lightened its touch and has even adopted policies that exhibit concern about the dismal fortunes of Hong Kong media companies. Yet it does so within a broader context of core support for its favored national media institutions, providing them with a host of benefits that protect their market leadership.

Today, Hong Kong is but one node in an increasingly dispersed circuit of deal-making and creative endeavor in the Chinese movie business, a business that is increasingly driven by the exigencies of the mainland market, which is governed by a regime that self-consciously aims to shape movie messages and build large national enterprises in hopes that they can compete with foreign counterparts. Occasional blockbusters do indeed circulate beyond East Asia, but the film industry is now renowned for a yawning gap between state-sanctioned extravaganzas and sadly undernourished mid-range and independent movies.[viii] Television likewise suffers from various institutional constraints, so that mainland China, which has by far the world’s largest national television audience, remains a net importer of programming.[ix] These institutional changes are manifested in the geography of Chinese media, which have suffered from a dispersion of talent and resources. Hong Kong, once the transnational center of Chinese film, television, and popular music, has suffered significant reversals since the late 1990s and is struggling to rebuild its creative capacity. Shanghai and Guangzhou media have exploded in size, but most companies are tied to provincial or municipal units of government and are constrained as well by regulations that favor state-sanctioned national champions, such as China Film and China Central Television (CCTV). Media enterprises in the provinces and cities are furthermore discouraged from building overseas distribution channels. Such privileges largely belong to Beijing-based institutions that sit snugly under the wing of the state, where they are closely monitored for content and tone.[x]

If today there is a geographic center to Chinese media, it is within the Communist Party offices in Beijing, not because the party micromanages the day-to-day operations of television and film companies but rather because it systematically doles out favors and franchises to those that acknowledge its supremacy. The party leadership is quite successful at keeping a leash on domestic players and at exploiting joint venture partners from overseas. News Corporation and Warner Bros. have both thrown in the towel after more than a decade of assiduous effort, and the general consensus among Western executives is that India is a better bet for investment these days. The Communist Party’s system of control is fairly obvious to viewers in the mainland who generally seek alternatives via the Internet and the robust black market in DVDs. Young people rely especially on Internet viewing, employing a host of strategies to circumvent the “Great Firewall” in order to acquire products that could never find their way into the cinema or onto the airwaves.[xi]

As for the Hong Kong movie industry, it has undergone a systematic process of resinicization since the 1990s, as leaders of the PRC have deftly wielded the carrot and the stick in order to tame the industry and bring it into the fold of nationally-sanctioned media institutions. This has undermined Hong Kong’s status as a transnational and relatively independent center of creative endeavor. Once known for its rambunctious, reflexive, and visceral cinema, the city’s creative community has shriveled and those that remain have, like Peter Chan, capitulated to a system that is built around the cautious, calculated blockbuster feature film that will appease state censors, party officials, and major financial backers. This is vastly different from the days when Hong Kong filmmakers pitched their products to local cinema circuits and overseas distributors. The movie business then operated outside the reach of national politics, sheltered by the benign neglect of the British colonial regime. Producers cobbled together movies in a freewheeling fashion and at a ferocious tempo, turning out popular products, occasional gems, and a good deal of rubbish. But the pace, scale, and diversity of production helped to foster a flexible ensemble of film companies that provided job opportunities to thousands of professionals as well as training for those that aspired to join the industry. Hong Kong became a magnet for talent from many mainland locales, such as Shanghai and Guangzhou, from Southeast Asian societies, such as Vietnam and Malaysia, and from Western abodes, such as London and San Francisco.[xii] It became home to Peter Chan, Maggie Cheung, and Leonard Ho. Home to Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, and Michelle Yeoh. Home to Peter Pau, Wong Kar-wai, and of course Bruce Lee. Today, however, Hong Kong is less a global media capital than it is a service center for a renationalized film industry that is orchestrated by the Communist Party leadership in Beijing. No longer a peer to Hollywood or Mumbai, it has become an appendage to a state system that benefits from a vast and putatively captive domestic market.

For many years Peter Chan tried to operate outside the gathering force field of the mainland market, testing the waters in Hollywood and fashioning features for pan-Asian audiences. Hollywood wasn’t his cup of tea and pan-Asian products worked for a while until it became apparent that they too needed to incorporate the mainland market into their aesthetic and financial calculations. These days Chan shuttles back and forth from Hong Kong to the mainland, hatching deals and making use of production facilities wherever he finds the most favorable rates. As best he can, he remains a Hong Kong-bred, Western savvy, pan-Asian filmmaker but he also has been forced to acknowledge the seemingly inexorable gathering force of the mainland movie market. Yet despite the PRC’s success at renationalizing commercial Chinese-language cinema, Beijing is not a media capital and likely will never become one. It will for the foreseeable future be a seat of national power where politics and favoritism mix uneasily with creative aspiration. Despite all the institutional clout of the Communist leadership and all the travails of the Hong Kong industry, the latter remains an influential presence in the Chinese movie business where today a handful blockbusters share the lion’s share of the annual box office with a carefully controlled quota of Hollywood imports. It is quite telling that the most successful domestic releases in the PRC each year are not projects hatched in Beijing but are rather coproductions that are conceived and executed by a geographically mobile ensemble of Hong Kong film personnel. Many of these films, like Peter Chan’s The Warlords, feature historical (and politically safe) themes, big budgets, and polished productions values. They perform well in mainland theaters, which are controlled by state-managed distribution and exhibition companies, but they tend to flounder overseas where audiences have more choices. Although Peter Chan has apparently succeeded under conditions that are not of his making, one wonders if he will ever feel at home in the renationalized cinematic space of the PRC.

Notes

[i] “A Discussion with Producer/Director Peter Ho-Sun Chan on Global Trends in Chinese-language Movie Production,” http://www.taiwancinema.com/ct.asp?xItem=58252&ctNode=124&mp=2.

[ii] Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh and Darrell William Davis, “Re-Nationalizing China’s Film Industry: Case Study on the China Film Group and Film Marketization,” Journal of Chinese Cinemas 2, no.2 (2008): 37-51; Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh, “The Deferral of Pan-Asian: Critical Appraisal of Film Marketization in China,” in Reorienting Global Communication: Indian and Chinese Media Beyond Borders, eds. Michael Curtin and Hemant Shah (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010); Yuezhi Zhao, “Whose Hero? The ‘Spirit’ and ‘Structure’ of the Made-in-China Blockbuster,” in Curtin and Shah; Tingting Song, “Independent Cinema in the Chinese Film Industry” (PhD diss., Queensland University of Technology, Queensland, 2010).

[iii] Chan interview, 2009.

[iv] Michael Curtin, “Media Capitals: Cultural Geographies of Global TV,” in Jan Olsson and Lynn Spigel, eds., Television after TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition (Duke University Press, 2004): 270-302; “Global Media Capital and Local Media Policy,” in Janet Wasko, Graham Murdock, and Helen Sousa, eds., Handbook of Political Economy of Communication (Malden: Blackwell, forthcoming); and Media Capital: The Cultural Geography of Globalization (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, in progress).

[v] Allen C. Scott, The Cultural Economy of Cities (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2000).

[vi] Richard Florida, Cities and the Creative Class (New York: Routledge, 2005).

[vii] Curtin, 2007; Joseph M. Chan, Anthony Y.H. Fung, and Chun Hung Ng, Policies for the Sustainable Development of the Hong Kong Film Industry (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, 2010); David Bordwell, Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, 2nd edition, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, forthcoming).

[viii] Yingjin Zhang, “Transnationalism and Translocality in Chinese Cinema,” Cinema Journal 49, no. 3 (Spring 2010): 135-139; Song, 2010.

[ix] Michael Keane, “Keeping Up With the Neighbors: China’s Soft Power Ambitions,” Cinema Journal 49, no. 3 (Spring 2010): 130-135.

[x] Ming Ming Diao, “Research into Chinese Television Development: Television Industrialisation in China” (PhD diss., Macquarie University, Sydney, 2008 ).

[xi] David Barboza, “For Chinese, Web Is the Way to Entertainment,” The New York Times 18 April 2010.

[xii] Michael Curtin, Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

Michael Curtin is the Mellichamp Professor of Global Studies in the Department of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His books include The American Television Industry (2009), Reorienting Global Communication (2010), and Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience (2007). He is currently working on Media Capital: The Cultural Geography of Globalization.

Post a Comment

Post a Comment

Reader Comments