X-Mission

by Ursula Biemann

[ PDF version ]

X-Mission (2008) is a video essay on the extra-territorial status of Palestinian camps and the refugees who inhabit them. It is conceived to be intensely discursive, an experiment in theoretical criticism of the multiple discourses which constitute the camp. In 40 video minutes it delivers something of a geological cross section through the juridical, philosophical, urban, post-industrial, mythological, and post-national narrative layers that articulate the highly compressed space. The speakers are explicitly labeled The Lawyer, The Architect, The Journalist, The Anthropologist, The Historian, The Refugee, unmistakably speaking from a particularly informed position. Together they form a dense narrative space, mirroring the compressed zone of the camp. In this anthology of remarkable expertise offered by various scholars, what takes shape for once is not the metaphorical waiting room for a disabled and interrupted history to pick up momentum again, but a veritable factory of ideas. In view of what could almost be described as an archeological endeavor, video is used as a cognitive tool to get to know the deeper strata of things.

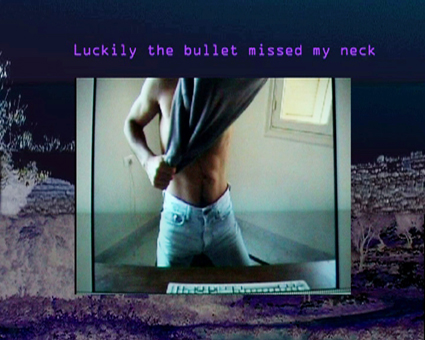

Video still from X-Mission

Like the many extra-territorial and otherwise exceptional spaces that have emerged in the wake of globalisation, contemporary refugee camps are designated spaces outside the national territory. Created in moments of crisis, camps are juridical zones of exception where populations get suspended from the political and civil rights that used to govern their lives. These populations become instead subordinated to the humanitarian conventions of the United Nations and the volatile domain of international politics.

The Palestinians are of particular interest here, because their case is not only the oldest and largest refugee case in international law, but it was instrumental in constituting the international refugee regime after the Second World War. This case exemplifies how international law itself failed to maintain a legal framework of protection, first depriving the Palestinians of their political rights as citizen by turning them, perhaps too quickly, into a speechless mass of refugees, and subsequently dispossessing them of the right of international protection guaranteed to all refugees.

Video still from X-Mission

The exceptional condition has made the Palestinian refugees particularly vulnerable to arbitrary reimpositions of the state of exception in the host countries Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, as well as in the West Bank. A recent incident, as explained by Ismael Sheikh Hassan, The Architect, in the chapter “juridical space,” shows how fragile the status of the camp-bounded refugee proves to be time and again. In the summer of 2007 the Lebanese Army breached international convention and entered Nahr el Bared, a Palestinian refugee camp in Northern Lebanon, to eradicate a small number of foreign Islamists who had settled in this isolated camp. The operation grew out of all proportion and instead of securing the refugees’ habitat, the army razed the whole camp, declaring it a “zone of exception.” In my ongoing artistic pursuit of generating counter-geographies, rather than focusing on the stratified and often ambivalent apparatus of sovereignty that rules this space, the video draws attention to the flexible process through which the refugees have begun to re-inscribe themselves into the political fabric. While the battle over Nahr el Bared was still under way, a community-based reconstruction committee was established to research the state of the camp prior to its destruction and draw up an accurate plan that would serve as the ground for negotiations.

Video still from X-Mission

Another case study of X-Mission, which I find most relevant in the context of this publication, is titled Refugee-Industrial Complex. In 2001, the U.S. established several Qualified Industrial Zones (QIZ) in Jordan and Egypt, where garments and other labor-intensive products are manufactured for tax-free export to the U.S., under the condition that the financial operation involved an 8% Israeli input. This neo-liberal initiative aimed at the normalization of Arab countries with Israel by way of the U.S.’s vision for a single economic zone stretching across the Middle East. Endorsed by Condoleezza Rice, the Free Trade Agreement for the QIZ was widely promoted as a peace-making measure in the region.

The incentive to agree to this arrangement was regarded by the Jordanians as an opportunity for the creation of a lot of jobs. Yet, the reality is that the majority of the workers in the QIZ were recruited by Asian manufacturers in China, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. Among the local workers, half come from Palestinian refugee camps located near the QIZs and the other half from villages in rural areas where jobs are hard to come by. The entanglement between the two extra-territorial spaces—refugee camp and free-trade zone—adds a different layer to the symbolic significance of the QIZ. Recruited among the poorest and most marginalized segments of the population, the Palestinian refugees find themselves, ironically, tied into an economic agreement that normalizes the very relations that segregate them.

There is a gender dimension that further complicates the configuration. Most of the workers recruited among Jordan’s rural populations or from the camps are women who have never been in the labor market before. It is their introduction to paid labor and to the public sphere at large. Here they are exposed to their male boss and to other women from different milieux, and sometimes even from different cultures, as is the case in the factories where Asian workers are intermingled with Jordanians and Palestinian refugees. They find themselves working side by side with Filipinas who come to work in shorts and t-shirts during the summer months.

Since most of the factories are producing garments and underwear, e.g., for the U.S. chain store Victoria’s Secret, the local women workers—whether they come from the camps or the villages—get exposed to fashion which has awakened their self-consciousness about their appearance and social interaction with others. However, the female wage is also problematic in a patriarchal family structure. It is evident that these exposures are experienced as stimulating by the women whereas they earn them a questionable reputation among men. Because female workers have not only become more “glamorous” by using make-up, fashionable accessories and perfume, they have also become more socially interactive and mobile, using their new revenue to finance trips to discover neighboring countries or go to the Hadj at Mecca which was hitherto unthinkable. While these Arab women can return to their families in the villages or the camps, the migrant workers from Asia often live in closed and overcrowded container cities. Their working and living condition is extremely precarious.

During my shooting trip, I visited the quarters of the Chinese workers in a concrete housing block on the fringe of the manufacturing zone. Six women are typically crammed into a small bedroom where curtains turn each sleeping area into a tiny private space. These quarters are in fact quite similar to student housing in China. As unbearable as they may seem at first sight, one has to consider them perhaps in the context of the dense urban condition of Chinese cities where these living arrangements are not all that unusual. Finding out how the Chinese workers personally feel about this lack of privacy was not permitted during my visit to their quarters. Apart from this, a lack of spare time, unpaid overtime, significant salary deductions for basic necessities, separation from their children for the two year duration of the contract: this is the price women from poor Chinese provinces are willing to pay for making headway in their life. Not surprisingly, crowded call centers and the frequent use of mobile phones enabling users to call to China at local server rates are omnipresent.

Chinese-run dormitories, Al Hassan Industrial Estate near Irbid, Jordan

The urge for communication in isolated zones is particularly pronounced in refugee camps. What X-Mission brings to light is that the attempt to confine people to a bounded space of refugee or labor camps typically instigates a heightened desire to connect across distances and activate new forms of trans-local contact. The refugee camp harbours an intense microcosm of complex relations to the homeland and related communities abroad. There is lively inter-camp and inter-diasporic communication going on among the widely dispersed Palestinian communities. A territory is no longer (strictly) a formal spatial arrangement but also a complex system of relations and large-scale structural networks. Given the vital importance of this connectivity, the video attempts to place the Palestinian refugee in the context of a global diaspora and reflects on post-national models of belonging that have emerged through the networked matrix of this trans-local community.

Although refugee camps are temporarily created in times of crisis, they tend to be consolidating and self-perpetuating. During the sixty years of their existence, Palestinian refugee tent cities, spread across the Arab world, have long since turned into precarious cinder block settlements. In the Palestinian case, the refugee camp must be apprehended as a spatial device of containment that deprives people of their mobility with the goal to condemn them to a localised existence, symbolically and materially asserted by the actual, extreme reduction of ground allocated to them. Yet, at the same time, the refugee camp is a product of supra-national forms of organization and administration (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, NGOs) and, in that sense, connected systemically to a historically specific global terrain. To render this condition visible, I opted for a form of a cultural report that includes local analysis by an array of experts while drawing on data and video material from YouTube, suggesting a use of media that connects the camp with the global distribution of power. Interspersed with multiple-layer video montage deriving from both downloaded and self-recorded sources, the interviews spin an intricate web of discursive interrelations.

Video still from X-Mission

Ursula Biemann is an artist, theorist and curator who has produced a considerable body of work on migration, mobility, technology, and gender. In a series of internationally exhibited video projects, as well as in several books, Geography and the Politics of Mobility (2003), Stuff It: The Video Essay in the Digital Age (2003), The Maghreb Connection (2006), and MISSION REPORTS (2008), she has focused on the gendered dimension of migrant labor from smuggling on the Spanish-Moroccan border to migrant sex workers in the global context. She is project director of Supply Lines, a current collective research project on global resource geographies, based at the Zurich University of Arts.

Post a Comment

Post a Comment