The Exit Sign: Off-Screen, In-Theater

Friday, May 24, 2019 at 12:37PM

Friday, May 24, 2019 at 12:37PM Zeke Saber

[ PDF Version ]

I. An Edgy Ontology

But suddenly a strange flicker passes through the screen and the picture stirs to life. Carriages coming from somewhere in the perspective of the picture are moving straight at you, into the darkness in which you sit; somewhere from afar people appear and loom larger as they come closer to you; in the foreground children are playing with a dog, bicyclists tear along, and pedestrians cross the street picking their way among the carriages. All this moves, teems with life and, upon approaching the edge of the screen, vanishes somewhere beyond it.—Maxim Gorky[1]

In his 1896 report on an early Lumière program, Maxim Gorky describes a phantom world destined to escape the limits of visuality. In this “Kingdom of Shadows,” every gray image surges vitally before disappearing from the screen or moving beyond it. Such transitions out of frame, off the edge of the screen, astonish Gorky—but not because the locomotive in the Lumières’ Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (France, 1896) will physically plunge into the theater. As Tom Gunning has argued, early cinema spectators were not so naive to believe the train would really barrel at them; rather, they were astonished by the illusion of projected motion. They reacted to a shocking moment of movement but never felt threatened by the film image.[2]

Figure 1. Lumiere Cinematograph.

For his part, Gorky finds the experience extraordinary, but less because the train might turn him into “a ripped sack full of lacerated flesh and splintered bones” than because it “disappears beyond the edge of the screen.”[3] At all times, Gorky finds the potential “thereness” and “thisness” of the film image undercut by its drift toward absence. As Gunning puts it, focus on the early film image “uncovered a lack, and promised only a phantom embrace.”[4] Right from the start, the essence of cinema was revealed to be without rather than within. Gorky’s “Kingdom of Shadows” is an early testament to this outlying power, and throughout this essay I will suggest that cinema continues to be haunted by an edgy ontology.

Due to the film image’s inherent elusiveness and the way it plays with presence and absence, Gorky must describe the experience with recourse to shadows and traces. These phenomena are usually peripheral signs of an originary source, but in Gorky’s account they occupy the center of his attention. For this reason he might be considered the first peri-phenomenologist of cinema. As outlined by philosophers like William Earle and Edward S. Casey, peri-phenomenology tends to be an approach that remains sensitive to the peripheral regions and outlying elements of things, places, and phenomena―to the edges or, as Casey puts it, “the very prominences and structures that attract our spontaneous glances.”[5] Peri-phenomenology focuses on the outstanding parts of things, places, and phenomena in order to show that those outstanding parts are integral to all that we experience. It brings to mind, according to Earle, “what has every chance of being lost sight of, that which is not seen, whose very essence is ‘to be lost sight of.’”[6] This approach would seem almost preternaturally drawn to a format that so dynamically engages the occlusive and disclosive practice of screening.

I would further contend that the peri-phenomenologist approach—adopted to a certain extent by Gorky in 1896—carries particular value at a time when the specter of expansion threatens the classical filmic experience, based as it is on the fixed and invariant arrangement of viewers, screen, and projector. Indeed, the very notion of a unique cinematic ontology would seem to be imperiled as theatrical cinema morphs into an edgeless, voluminous supercinema. Whether by eliminating the screen entirely or by extending it to cover the full field of vision, the force of cinematic history tends toward the expansion of representational limits and the erasure of the apparatus—not to mention the erasure of cinema as such, given André Bazin’s reminder that total cinema would cease to be cinema at all.[7] In a media environment dismissive toward the classical filmic experience and its delicately codified architecture of vision, on what basis can we argue for cinema’s unique essence? In his work on the future of film studies, Gregory Flaxman has asked a similar question, and he has advocated a novel response, one that lies perversely “out of field.” Invigorated by Gilles Deleuze’s definition of the outside as “the point where and when we dispense with presuppositions and define thought itself as a problem,” Flaxman endeavors to affirm cinema’s singularity “on the basis of that which lies beyond the limits of the visible.”[8] This notion of cinematic ontology resonates with that in Gorky’s “Kingdom of Shadows,” which implies that the essence of cinema lies without rather than within. Further, as a tactic for radical and emergent thought, it also aligns with Casey’s elucidation of “thinking on the edge,” which unsettles predominant concepts and systems of thought by contesting and diversifying limits.[9]

But at a time when (1) the limits of the cinema screen are being expanded to fill the spectator’s entire visual field, and (2) certain media are starting to envision an inhabitable and enveloping sensorium, how can we even find cinema’s edge, much less think on it? Can cinema’s edgy ontology be sustained in such a media environment? Consider, for instance, how recent patents for so-called supercinema theaters detail attempts to expand the screen and thereby eliminate its delineating function by monopolizing the spectator’s gaze.[10] This state of engulfing seems to portend the passing of cinema in favor of a total cinema without edge or exit. Whereas edges and glances are “mercurial in their evanescence,” limits and gazes allow no surfeit perception and therefore no escape from their categories of understanding.[11] The out of field atrophies in such situations. However, there may be egress yet. Buoyed by Flaxman’s insistence on the out of field and by Casey’s peri-phenomenologist approach, I want to use the remainder of this essay to develop a speculative line of thought about a peripheral cinema object. In our changing media environment, cinema’s edgy ontology may well be sustained by a source beyond the limits of the screen: the emergency exit sign.

II. The Emergency Exit Sign in Plato’s Cave

There are things like that in Plato?—Jean-Louis Baudry [12]

Omitted in the founding texts of apparatus theory, the emergency exit sign casts a spectral light over discussions of the cinematic viewing situation. How was such a crucial element of the theater’s technical ensemble excluded from discussions of the basic cinematographic apparatus (l’appareil de base)? Even though writers like Jean-Louis Baudry (especially in his seminal essay, “The Apparatus: Metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in the Cinema”) argue that the distinctive technical ensemble and spatial organization of different elements in the theater establish and restrict the effects cinema can have on a spectator, the exit sign is never considered. If the actual arrangement of the theater contributes to the virtual work of the apparatus (le dispositif), then wouldn’t the illumination of the exit sign inflect that virtual work? The oversight seems odd, but perhaps it is unsurprising that an exit sign would not be mentioned in apparatus theory. After all, the cinema situation—in the hands of writers like Baudry—became an omnipotent, insurmountable, and inescapable ideological machine. The exit sign is absent because there can be no egress from this system of utterly impregnable coherence and reach.[13]

And yet an alternative genealogy of the cinematic viewing situation might even begin with the need for egress during states of emergency. This is true not only from a historicist perspective but also a mythological one. For if the audience of Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat fled in terror from the oncoming train, where did they flee other than for the exits? And if the prisoner in Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”—so crucial to Baudry’s theorization of the apparatus—avoids the plight of illusive reality, isn’t it because he follows the illuminated path out? But even putting mythology aside, it is clear from a historicist perspective that the need for egress during states of emergency affected the cinematic viewing situation. Fire risk in particular determined movie theater architecture.

Figure 2. Interior of the Iroquois.

Another subheading

The Iroquois Theatre fire, which killed more than six hundred people on 30 December 1903, remains the deadliest single-building fire in United States history and marks a key turning point for fire safety reform and modern theater architecture. Poorly illuminated exits contributed to the high death toll at the Iroquois Theatre, so after 1903, requirements were set concerning the illumination of exits, aisles, and corridors, with the further stipulation that exit lights should run on their own electric supplies.[14]

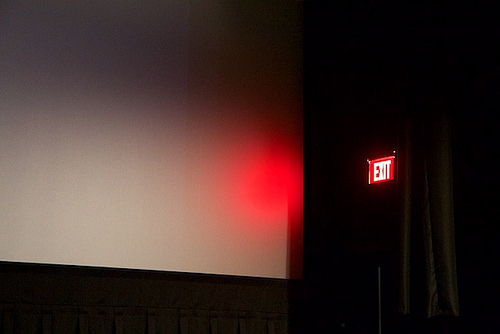

These glowing red exit lights were early versions of the omnipresent, text-based American exit sign, which has its origins in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire.[15] By 1915, these exit signs had become official elements of the basic cinematographic apparatus (l’appareil de base) and were even proximate to the apparatus’s “imaginary mirror of spectatorial desire,” the silver screen itself.[16] As Amir Ameri explains:Once admitted, the experiential journey that had started on the sidewalk would be merely prolonged by the directional space of the nickelodeon’s auditorium. The directionality of this space had as much to do with the physical dimensions of the often narrow and long auditoriums as with the strategic location of the screen at the far end of the room. As the focal point of this directional space, one’s movement in the auditorium was progressively toward, though never arriving at the literal place of the imaginary: the screen. Placing the screen at the far end of the auditorium was not, however, the only option. Besides the side walls, John Klaber noted in 1915, ‘[t]he type of hall where the screen is at the same end as the main doors has been advocated by some authorities as lessening the fire risk, since the audience faces toward the principal exits, and need not pass the operating room to reach them.’ Practical as this placement would have been, it would have also drastically altered the experience and with it the intended relationship between the real and the imaginary. Consequently, fire exits were placed, at some expense, in proximity to the screen to allow the latter to remain in its desired location at the far end of the auditorium.[17]

Undisputed as the key element of the theater’s technical ensemble yet acquiescent to the strictures of fire safety reform, the screen was obliged to welcome the exit sign on its borders. And there the sign remains, an auxiliary light source on the edge of the screen, an object of the glance but never the gaze.[18] Parergon of the theater,[19] the exit sign casts an “intermittent moonlight,”[20] and it is precisely in this oscillating luminescence—in the way it perpetually toggles between figure and ground, visibility and invisibility—that the exit sign authorizes a mode of discretionary bliss unaccounted for in apparatus theory. Like seeing cigarette smoke rise to meet the projected light cone, glancing at the exit sign allows one to be both within the theater and departing it—to engage in a “doubled erotics,” as Roland Barthes would say. The tremulous action of alternately gazing at the screen and glancing at its edge produces transfixion of a different order than ideological oppression. Seen at an “amorous distance,” the exit sign allows for rapt disengagement within the apparatus.[21] Importantly, the latent power of the exit sign should not be confused with the fantasy of total exit, which Sarah Sharma has shown to be a patriarchal penchant and inclination. Its power has more to do with nonproductive expenditure and finding a modality within the apparatus that nevertheless evades regulation.[22]

Figure 3. Exit sign beside screen.

That freeform modality—the exit sign’s edgy power—has been consistently threatened by the drive toward total cinema. Consider, for instance, the Anthology Film Archives’s 1970 Invisible Theater, which built side blinders into the seats to rivet spectator attention to the screen rather than its periphery.

Figure 4. Invisible Theater.

Here, all forms of supplemental gratification were rejected in the hopes of establishing an insulated cult of absolute attention. “Even the minimally luminous exit signs,” notes Annette Michelson, “were an unwilling concession to the fire department’s strictures.”[23] But if the fire department had insisted on minimally luminous exit signs in the Invisible Theater, it was only because the department had already conceded so much else. Some twenty years earlier at Cinerama’s premiere at the Broadway Theatre in New York City, the screen had been so large that the original asbestos curtain could not be lowered—and yet the fire department waived its usual strictures to permit the theatre to operate.[24] One of several types of expanded cinema that emerged in the 1950s, Cinerama remains an early example of how the drive toward total cinema often bypasses established safety strictures. But of course, as the pesky exit signs in the Invisible Theater indicate, efforts to eliminate cinematic periphery have always proved futile.[25]

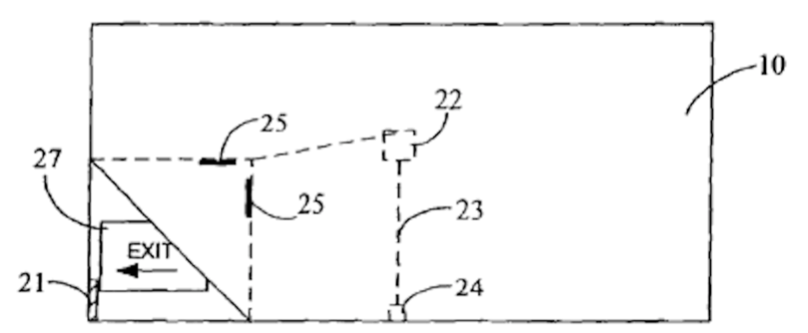

The eventual apotheosis of such fraught efforts occurred in 2006, with the issuance of US Patent 7,106,411: “Conversion of a Cinema Theatre to a Super Cinema Theatre.” This patent explains how to expand the cinema screen and thereby eliminate its delineating function by monopolizing the spectator gaze. In the process though, this new supercinema theater hides the emergency exit sign beyond the expanded screen. In the event of a crisis, the sign is revealed through an automated process whereby the screen gets pulled away like a skin graft:

In an emergency situation, an automatic activation means sends a signal to electromagnets 22 switching them off thereby removing the magnetic force which had been holding the metal rods firmly against the wall and floor of the theatre. The corner of the projection surface of screen 10 is then pulled backwards and upwards by the counterweight as it falls by gravity towards the ground. FIG 8 [see fig. 5] depicts the system door to the emergency exit in an activated position with the corner of screen pulled upwards and backwards and counterweight 24 resting on the ground.[26]

Figure 5. Supercinema exit sign.

The supercinema theater attempts to unify the limits of representation with the edges of our visual field, hiding the exit sign in the process. Firstly, there is potential danger here in the return to a pre-1903 theatrical situation, where egress may become visually or physically obstructed (what if the contraption malfunctions?). Secondly, there is potential conceptual danger in the sense that the supercinema viewing situation seeks to eliminate all potential edges by expanding the limits of representation. It seems to abide no surfeit perception, no thinking on its edges, and therefore no escape from its self-prescribed categories of understanding. But at this point it is worth remembering that the peri-phenomenologist approach is, as Casey writes, “not just edge-savvy but edge-creative; it is not only a matter of knowing edges or focusing on them but also of bringing them into being.”[27] A peri-phenomenologist project would do more than note the exit sign’s banishment; it would also evince how the out of frame has simply moved behind the screen rather than beside it. The edge was not annihilated; it just moved outside our field of vision. Even now the exit sign promises to irrupt through supercinema’s membrane, reminding us that the Deleuzian outside lingers behind the screen as well as beside it. The essence of cinema has always been without rather than within, and this edgy ontology ensures that the exitless suffocation of total cinema—its regulatory force—will remain on the verge.

Notes

[1] “Maxim Gorky on the Lumière Program, 1896,” trans. Leda Swan [Jay Leyda], in Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film, ed. Jay Leyda (New York: Macmillan, 1960), 407–9.

[2] Tom Gunning, “An Aesthetic of Astonishment: Early Film and the (In)Credulous Spectator,” Art & Text 34 (Spring 1989): 31–45.

[3] “Maxim Gorky on the Lumière Program, 1896,” 408.

[4] Gunning, “An Aesthetic of Astonishment,” 43.

[5] Edward S. Casey, The World on Edge (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017), 53–54.

[6] William Earle, Evanescence: Peri-Phenomenological Essays (Chicago: Regnery Gateway, 1984), 8.

[7] André Bazin, “An Aesthetic of Reality: Neorealism,” in What is Cinema?, vol. 2 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972), 26–27. On the subject of cinema’s drive toward total cinema, see Akira Mizuta Lippit, “Three Phantasies of Cinema—Reproduction, Mimesis, Annihilation,” Paragraph 22, no. 3 (1999): 213–27. As Lippit forcefully argues, 3D cinema in particular reveals “a fundamental desire to eliminate the last vestige of the apparatus from the field of representation, the film screen” (214). But further,

a perfected cinema would be would be deeply anti-cinematic. Three phantasies that sustain cinema—reproduction, mimesis, annihilation—drive it toward extinction, turning it before the fact into an exemplary lost object. The desire for a 3D cinema that seeks to eliminate the last material vestige of the apparatus, the screen, can be seen as a symptom of such unacknowledged mourning. 3D cinema makes visible the end of cinema as such—an end marked by the disappearance of cinema as well as its completion. (222–23)

[8] Gregory Flaxman, “Out of Field: The Future of Film Studies,” Angelekai 17, no. 4 (December 2012): 130, 120. At the end of this well-wrought essay, Flaxman issues the following directive:

The cinema is uniquely capable of rendering the reality of the virtual, the unthinkable, the outside. Even as the digital image erodes this cinematic power, or perhaps precisely because it does so, we ought to make the off-screen the source of a new critical agonism. Today, more that ever, we ought to lay claim to the concept of the outside as the most rigorous description of the cinema and the most unrelenting critique of the digital means and media that claim to have superseded it. (133–34).

[9] On the difference between limits and edges, Casey writes:

We glance at the edge, aware that it harbors the unexpected—not only as what is concealed from present perception but as the not-yet-happening: the event-to-come. Edges, like places and glances, are creatures of becoming, not fixed instances of being. Just as places complicate space, and glances undercut gazes, so edges contest limits: they diversify limits from around and under and beyond them, immanently, even as limits present themselves as fixed and transcendent. Such is the sub rosa subversive force of edges that their subordination under the presumed priority of limits is resisted and undone by the very character and operation of edges themselves. Formally imposed limits are deconstructed by the teeming energy of the very edges that cluster about them.(55)Also: “Here, the rule is, no edges without a limit that superintends them; no limit without edges that complicate it and populate its otherwise empty ideal space” (52, italics in original).

[10] See, for instance: Steven Charles et al., “Conversion of Cinema Theatre to a Super Cinema Theatre,” US Patent 7,106,411, issued 12 September 2006.

[11] Casey, The World on Edge, xviii, 46.

[12] Jean-Louis Baudry, “The Apparatus: Metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in the Cinema,” in Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology: A Film Theory Reader, ed. Philip Rosen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 303.

[13] The best synthesis of apparatus theory and its resultant critiques is: Judith Mayne, Cinema and Spectatorship (London: Taylor and Francis, 1993).

[14] See Francine Uenuma, “The Iroquois Theater Disaster Killed Hundreds and Changed Fire Safety Forever,” Smithsonian, 12 June 2018.

[15] “The text-based American exit sign,” writes Julia Turner,

has its origins in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, a blaze in a downtown Manhattan garment factory that killed 146 workers. Although signage was not primarily to blame for those fatalities—many factory doors were bolted shut in an effort to keep employees from slipping out—the exits were not clearly marked. That massive loss of life spurred the National Fire Protection Association, which had been founded in 1896 by insurance companies to develop protocols for property preservation, to take up what it called ‘life safety’: the business of getting people out of burning buildings intact. In the 1930s and ‘40s, the NFPA developed criteria for emergency-exit signage, evaluating contrast levels and testing different sizes and stroke widths for lettering, eventually publishing standards that were adopted by state and local governments across the land.

See Julia Turner, “The Big Red Word vs. the Little Green Man: The International War Over Exit Signs,” Slate, 8 March 2010.

[16] Thomas Elsaesser and Malte Hagener, Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses (New York: Routledge, 2010), 88.

[17] Amir Ameri, “Imaginary Placements: The Other Space of Cinema,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 69 (Winter 2011): 86–87. The quoted material is sourced from John J. Klaber, “Planning the Moving Picture Theatre,” Architectural Record 38 (1915): 550.

[18] Indeed, sound engineers worried about the so-called “exit sign effect” try to ensure that attention never lands on these objects for too long. The belief that audiences should face the screen at all times led Dolby-era sound practitioners to channel sound effects through loudspeakers in front of (rather than behind) the audience—all in order to mitigate the risk of the audience looking away from the immersive spectacle on screen and becoming cognizant of their immediate architectural surroundings, such as the exit signs. See Eric Dienstfrey, “The Myth of the Speakers: A Critical Reexamination of Dolby History,” Film History 28, no. 1 (2016): 185.

[19] The emergency exit sign’s relationship to the projected film in the darkened theater is supplementary in the sense that Jacques Derrida uses the term parergon: “A parergon comes against, beside, and in addition to the ergon, the work done [fait], the fact [le fait], the work, but it does not fall to one side, it touches and cooperates within the operation, from a certain outside. Neither simply outside nor simply inside. Like an accessory that one is obliged to welcome on the border.” Jacques Derrida, The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 54.

[20] Dorothy Richardson, Close Up, 1927–33: Cinema and Modernism, ed. James Donald, Anne Friedberg, and Laura Marcus (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998), 169.

[21] The phrases “doubled erotics” and “amorous distance” both come from “Leaving the Movie Theater.” In this poetic and clever essay, Barthes negotiates between apparatus theory and its classical critiques, specifically by describing a film-viewing affect that borrows from each side but exceeds them both. Roland Barthes, “Leaving the Movie Theater,” in The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1986), 345–49. For an enlightening discussion of smoking in the movie theater and the cigarette’s necessity for understanding American cinema spectatorship, see Jocelyn Szczepaniak-Gillece, “Smoke and Mirrors: Cigarettes, Cinephilia, and Reverie in the American Movie Theater,” Film History: An International Journal 28, no. 3 (2016): 85–113.

[22] Sharma’s argument was made at the 2017 Marshall McLuhan Lecture (“Exit and The Extensions of Man”), delivered as a keynote address at the Embassy of Canada on 31 January 2017—accessible on YouTube as “Transmediale Marshall McLuhan Lecture 2017 by Sarah Sharma.” For a discussion of what might constitute nonproductive expenditure in late capitalism, see Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (London: Verso, 2013). For what this modality of viewership might look like in practice, consider Jean-Paul Sartre’s visit to the theater:

Above our heads, a shaft of light crossed the hall; one could see dust and vapor dancing in it. A piano whinnied away. Violet pears shone on the walls. The varnish-like smell of a disinfectant would bring a lump to my throat. The smell and the fruit of that living darkness blended within me: I ate the lamps of the emergency exit, I filled up on their acid taste. I would scrape my back against knees and take my place on a creaky seat. My mother would slide a folded blanket under my behind to raise me. Finally, I would look at the screen.

Jean-Paul Sartre, The Words: The Autobiography of Jean-Paul Sartre, trans. Bernard Frechtman (New York: George Braziller, 1964), 120. Emphasis mine.

[23] Annette Michelson, “Gnosis and Iconoclasm: A Case Study of Cinephilia,” October 83 (Winter 1998): 5.

[24] John Belton, “The Curved Screen,” Film History: An International Journal 16, no. 3 (2004): 278.

[25] On one level, this may be attributable to the faulty logic of merely substituting one regulatory scheme (the fire department’s) with another (blinders on the seats).

[26] Charles et al., “Conversion of Cinema Theatre to a Super Cinema Theatre,” 8.

[27] Casey, The World on Edge, 360.

Zeke Saber is a PhD student in Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Southern California (USC). His areas of focus include filmic realism, metaphor theory, post-cinema, and immersive technology. Zeke’s work has been published in Cinephile, Film & History, and Mediascape (forthcoming).