Re-Imagining Zine Movements: Tenacious, a Prisoner-Made Zine, and the People of Color Zine Project

Wednesday, December 4, 2013 at 8:54PM

Wednesday, December 4, 2013 at 8:54PM Red Chidgey

[ PDF Version ]

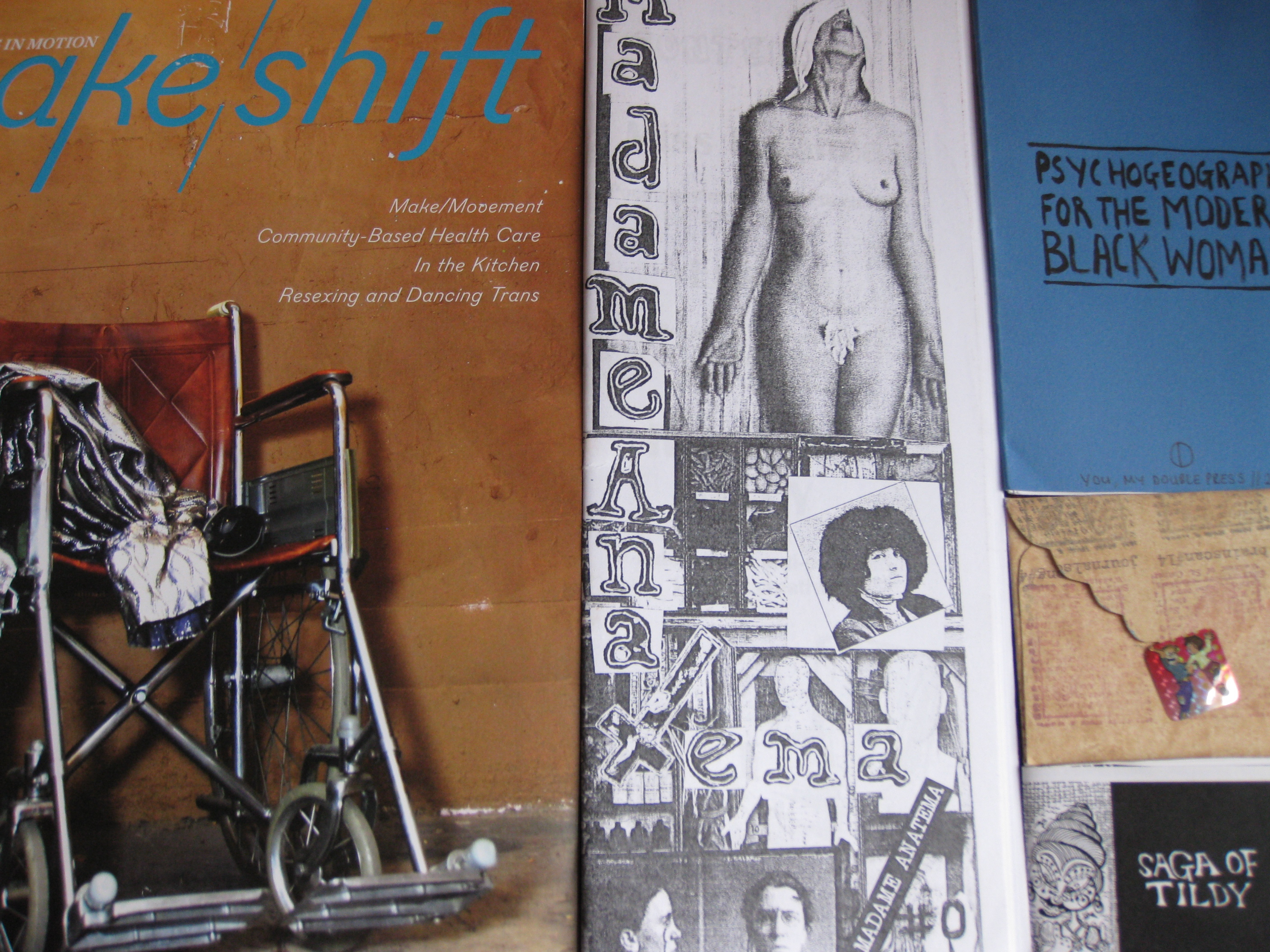

Figure 1. Feminist zines from the U.S., Mexico, and the U.K.

As an alternative form of media, zines are low-budget, do-it-yourself publications. Produced by individuals as well as collectives, these publications vary from photocopied pamphlets exchanged with friends to slick magazines circulating within alternative distribution networks (see Figure 1). As alternative media scholar Stephen Duncombe has suggested, “In an era marked by the rapid centralization of corporate media, zines are independent and localized.” For Duncombe, however, these publications exert a limited political capacity, being “merely a form of political catharsis” and “a rebellious haven in a heartless world.”[1]

This essay presents two US zine projects that challenge conventional understandings of zine production as leisure-based or politically sublimated activities typically carried out by white, middle-class youth. These projects are Tenacious, a zine made by and for incarcerated women, and the People of Color Zine Project, a network which seeks to place people of color’s grassroots publishing firmly on the critical radar. To provide the theoretical framework for this essay, I draw upon Adela C. Licona’s conceptualization of zines as “third spaces” to elaborate how zines are mobile, dynamic sites of articulation, and Alison Piepmeier’s consolidation of feminist zines as sites of intersectional analysis. My intention here is to emphasize some under-recognized spatialities of zine production and reception: the mobile and regulated sites where these media forms are made and accessed, and the critiques of power and privilege carried out within their pages and broader communication channels.[2]

Zines as Third Space and Intersectional Texts

In her article “(B)orderlands’ Rhetorics and Representations: The Transformative Potential of Feminist Third-Space Scholarship and Zines,” Adela C. Licona draws on the “third-space” theory of Chela Sandoval[3] to argue that feminist and queer zines move beyond binary demarcations in order to express the fluid, ambiguous, and hybrid nature of lived identities. As Licona writes,

Third space can be understood as a location and/or practice. As a practice it reveals a differential consciousness capable of engaging creative and coalitional forms of opposition to the limits of dichotomous (mis)representations. As a location, third space has the potential to be a space of shared understanding and meaning-making. Through a third-space consciousness then dualities are transcended to reveal fertile and reproductive spaces where subjects put perspectives, lived experiences, and rhetorical performances into play.[4]

Such practices can be found in queer/feminist zines documenting LGBTIQ [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer] subjectivities and activism, such as publications calling for gender-liberated restrooms. These calls draw attention to how male- and female- designated restrooms exclude and potentially threaten transgender and queer people, as their embodiments are challenged and declared wrong, and can sometimes lead to confrontation. No-border activism, transracial relationships and solidarities, surviving sexual violence, migration experiences, and moving between class locations: these scenes of writing and embodiment are further instances of potential third space political articulations—blurring the divide between them/us, personal/public, taboo/speaking out, of challenging binary identity formations, and of creating political speech acts and sites for social justice demands.

Such concerns are further examined in Alison Piepmeier’s Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism, the first book-length analysis of women and queer produced zine cultures.[5] Detailing a genealogy of zine production that extends to the US women’s suffrage and women’s liberation movements, Piepmeier characterizes feminist zines as embodied, material artefacts, infused with passion and emotion, which create vernacular spaces for articulating personal experience and sharing these theorizations with a reading community. Zines are viewed as mobile sites capable of negotiating the intersections of race, ethnicity, sexuality, class, and history. Optimistic about the political potential of these media forms, Piepmeier suggests that zines “are rich primary sources, sites where girls and women document and construct their lives, and where they articulate and illustrate third wave feminist theory.”[6]

Building on these conceptualizations, this essay focuses on two zine projects in particular: Tenacious, a prisoner-made zine produced by and for incarcerated women, and the People of Color Zine Project, a multi-platform initiative which seeks to foster dialogue and collaboration between zinesters of color. These two projects provide strong examples of zine networks that push against the commonplace understandings of zine production as primarily white and limited in scope and circulation.[7] Whereas girls’ and young women’s zine production is often viewed as engendering a “no rules” approach, operating as a site of open expression, these projects serve as important reminders of the constraints placed on zine makers and their work—particularly within regulatory prison systems or white-dominated networks. These projects demonstrate how zines can embody resistance and third space voices: voices often ignored within hegemonic mainstream media and broader (sub)cultural scenes.

Prisoner-Made Zines: Empowerment and Advocacy Media

Launched in 2003, Tenacious is written predominately by incarcerated women for incarcerated women. The publication came into being after the zine producer Vikki Law[8] was approached by incarcerated women in an Oregon prison to become their outsider publisher and co-editor, following a lack of response from mainstream media channels to publish their work. As Law contextualized this situation in an interview with me, “People inside prisons do not have access to printers, copy machines, massive amounts of postage and all the stuff that we zinesters on the outside may take for granted . . . even in the age of blogs and the widespread use of the Internet, there are populations of women who are cut out of the information loop. Incarcerated women are one such population.”[9]

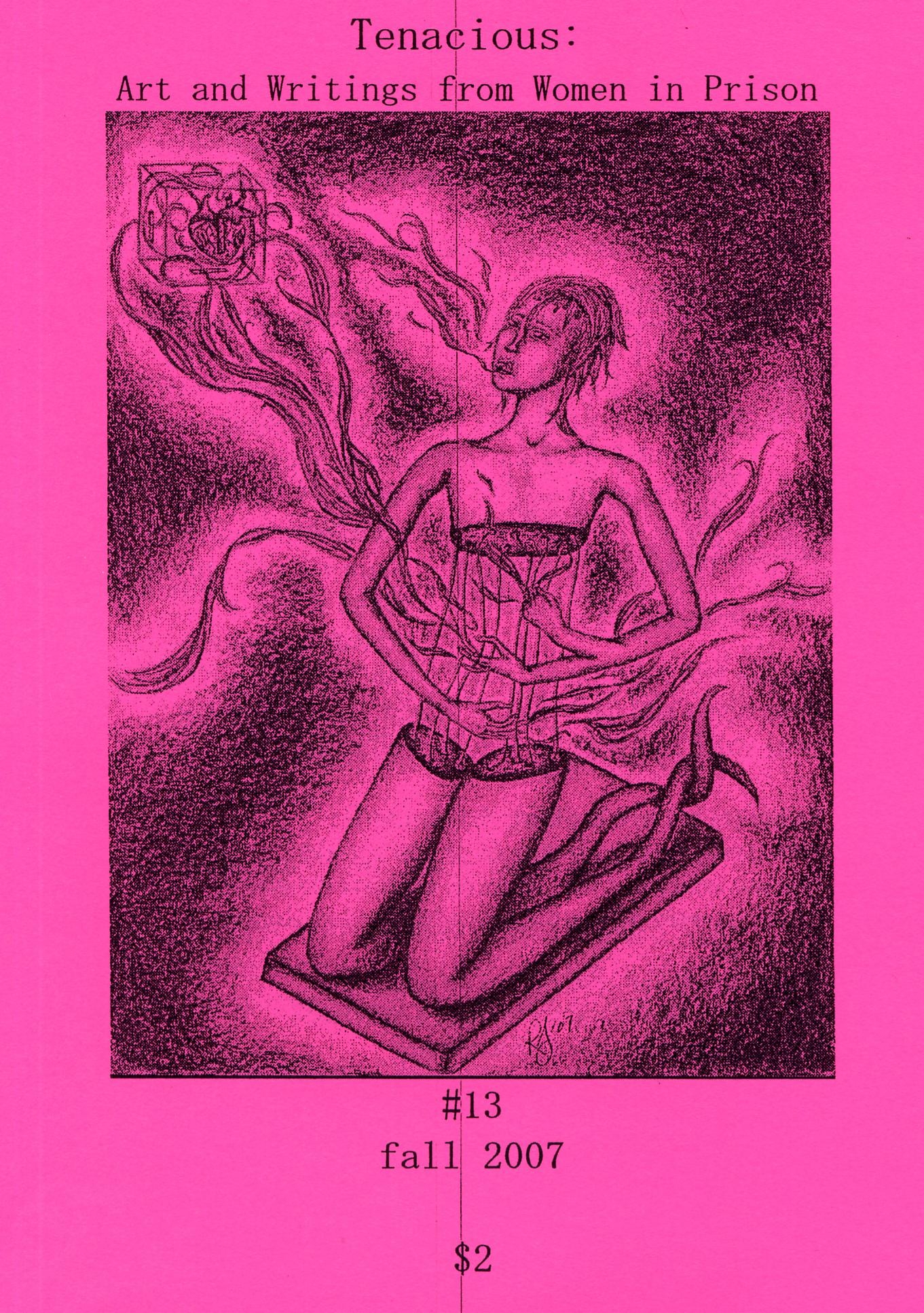

Figure 2. Tenacious Zine: Art and Writings from Women in Prison

Tenacious provides a vital space for communicating women’s experience, oppression, and resistance within prison systems (see Figure 2). Zine topics can include discussions of the lack of health care provisions, being HIV-positive in prison, enduring sexual harassment by prison staff, and the pain of being forced to give up children for adoption. To produce the zine, Law collates the articles, poetry, and artwork submitted to her, corresponds with prisoners, writes about issues affecting incarcerated women and their collective resistance, and works to place these writings in broader media channels.

Due to prison censorship, zine content can be seized and their authors penalized; the stakes are high for such media production. As Law told me:

Some women in federal prisons have access to e-mail and have been able to e-mail me their writings. E-mail seems to be more easily censored by the prison authorities. . . . In one case, the woman’s e-mail access was taken away and she was threatened with being placed in the SHU (Special Housing Unit or solitary confinement). . . . This is also true with snail mail, but I think that mailroom staff are a lot less likely to read each and every letter coming through (whereas with e-mail, a computer program can probably pull out words and phrases that might be seen as “threatening to the safety and security of the institution.” This is the actual phrasing that prisons use to justify banning reading material.) In one case, in a state prison in Oregon, a woman was trying to send out a drawing that depicted a female prisoner who had obviously just been sexually assaulted. In the background of a drawing, one could see the back of a correctional officer (the euphemistic term for “prison guard” here in the United States) walking away. The mailroom confiscated the drawing and she received several visits from prison administrators about that drawing.

As Law continued, “In some cases, the prison has censored the zine. In Oregon, after I published an article about guards harassing a lesbian couple because of their sexual orientation, that particular issue was banned.”

Tenacious creates a vital outlet for incarcerated women’s stories and experiences where few options exist for public telling and recognition. The zine also has a role to play in broader activist and zine cultures. As Law reflected in our interview: “At the time, I didn’t see any media devoted solely to [incarcerated women’s] issues and experiences. I think it’s raised awareness among people who do prisoner support and prisoner rights work for men; women haven’t really been seen by many of these activists. At the same time, having it in zine format has also raised awareness among people in the zine community.”

Though one might see Tenacious as a queer/feminist zine, the publication traverses such labels, and women involved in the project might reject such terms. As Law herself indicated in our interview, as a woman of color, “the term ‘feminism’ still seems pretty loaded with white, middle-class values (at least here in the US) that I don’t feel all that comfortable using that term for myself.” As to the significance of zines effecting social change and transformations on a feminist level, Law relates:

I’ve had women in their twenties ask me to send them information about feminism because they don’t know much about it or they have always seen it as a white, middle-class issue and since the majority of those in prison are not white, middle-class folks, they didn’t relate to these ideas or issues while on the outside. Women have also told me that they’ve shared the material I’ve sent them—about feminism, politics, ideas surrounding prison abolition and the question “what do we do if we don’t have prisons?”—with the other women around them. In some prisons, it’s sparked discussions among women about ideas around patriarchy, sexism, [and] the necessity of speaking out.

The POC Zine Project: An Experiment in Community through Materiality

Figure 3. POC [People of Color] Zine Project tumblr.

If zines are about starting new conversations and discussions, part of the problem of building zine culture is memory: how to hold on to legacies surrounding ephemeral cultural production and to resist white erasure of the work and politics of communities of color. Documentation, legacy creation, and physical encounters form an important part of the People of Color Zine Project, which brings zinesters of color’s cultural and political expression to the fore (see Figure 3). As a response to the continuing erasure and marginalization of people of color’s input within zines scenes, Daniela Capistrano founded the POC Zine Project in 2010 with the aim to “make ALL zines by POC (People of Color) easy to find, share and distribute.”[10]

Public events are part of this initiative. See the panel below, “Beyond Meet Me at the Race Riot: People of Color in Zines from 1990– Today,” hosted at Wellesley College on 15 September 2012, for an example of embodied recovery work by members of this project in relation to people of color’s zine production over the past few decades in the US.

Launched as “an experiment in activism and community through materiality,” the POC Zine Project has forged a multitude of new coalitional spaces, digitally and in real time. Actions include a dedicated archive and digital platform, intern positions for zinesters of color, and annual zine tours through US cities.

Part of the POC Zine Project is about opening up POC zine-making to new audiences. During a 2011 speaking tour, Capistrano visualized bringing zines into academia and classrooms as a new form of social pedagogy:

Our long term vision is to have a traveling archive that not only gives people a physical opportunity to interact with the zines, but also to put workshops in place with schools, to teach a whole new generation how to tell their own stories and to bridge the gap between academia and everyday people. Because a lot of kids don’t see higher education as an opportunity, for a lot of different reasons. And things like independent media can definitely bridge that gap, or at least it can be one of the tools.[11]

Spaces of the “grassroots” and the “institutional” are strategically blurred here, with POC zines mobilized as social justice resources, not only for their ability for marginalized groups to “see themselves” culturally represented in nuanced ways, but also as means to facilitate imaginative resources for engagement, aspiration, and critique. As Capistrano emphasized in connection to the POC Zine Project in her speaking engagements, such work becomes a “catalyst for change,” not only for survival and social justice, but for creativity and connection too.

Conclusion: Consolidating a Social Justice Media Vision

Through a focus on Tenacious and the People of Color Zine Project, this essay has highlighted people of color-led zine networks operating through a range of sites: within and between prison systems, on the road via zine tours, online, and in educational and institutional spaces. These projects constitute a form of movement media. Print zines move between the spaces where digital information loops might not reach and help create low-threshold opportunities for voice and representation within regulated, punitive, or otherwise inhospitable contexts. Beyond “a rebellious haven in a heartless world,” to recall the critique of zine scholar Stephen Duncombe presented at the beginning of this paper, such zines travel as affective micro-media, capable of transmitting experience, ideas, and theory about social change, and of moving participants to speak out and organize. Persisting within a digital age, and indeed reaching places where the digital divide falls, these zine projects create new pathways of articulation, new scenes of advocacy and social justice work, and vital new media histories for the future. Their archives are being established from the grassroots up and constitute multi-vocal and nuanced convergent points for third space identity, politics, and cultural practice.

Notes

Many thanks to Vikki Law, Daniela Capistrano, and the zine-makers whose works and projects are discussed in this essay.

[1] Stephen Duncombe, Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture (London: Verso, 1997), 2, 190.

[2] A historically male-dominated cultural practice, a “girl zine explosion” took place in North America and beyond in the 1990s, supported by the burgeoning queercore and riot grrrl music scenes. Zine cultures continue to thrive today, with the Grrrl Zine Network documenting feminist, queer, and transgender zine publications spanning six continents. See the website for Grrrl Zine Network: grrrlzines.net.

[3] Chela Sandoval, Methodology of the Oppressed: Theory Out of Bounds (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000).

[4] Adela C. Licona, “(B)orderlands’ Rhetorics and Representations: The Transformative Potential of Feminist Third-Space Scholarship and Zines,” NWSA Journal 17, no. 2 (2005): 105.

[5] Alison Piepmeier, Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism (New York: New York University, 2009). See Adela Licona, Zines in Third Space: Radical Cooperation and Borderlands Rhetoric (Albany: State University of New York, 2012) for the first book length analysis of people of color queer and feminist zines.

[6] Piepmeier, Girl Zines, 200.

[7]Genealogies of the POC zine project and Tenacious can be placed within broader histories of political publishing by people of color and prison-abolitionist movements. See Victoria Law, Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women, 2nd ed. (Oakland, California: PM, 2009); Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, “Brown Star Kids: Zinemakers of Colour Shake Things Up,” Broken Pencil, no. 24 (2004): 25–26.

[8]Law co-founded “Books through Bars-New York City,” a group that sends free books to prisoners nationwide in 1996, and is a prominent activist and author on prison abolition.

[9] “Tenacious: Art and Writing from Women in Prison. An interview with Vikki Law from New York, United States,” 13 February 2009, www.grassrootsfeminism.net/cms/node/117.

[10] POC Zine Project, poczineproject.tumblr.com (accessed September 5, 2013). There are organic connections between Tenacious, third space ideas and the POC Zine Project. For online copies of Tenacious and a recent interview with Law by POC Zine Project founder Capistrano see http://poczineproject.tumblr.com/search/Tenacious; for a report of the 2013 Allied Media Conference and a zine-making workshop with Licona see http://poczineproject.tumblr.com/post/ 53605243354/scene-report-june-21-2013-allied-media-conference.

[11] “Meet Me at the Race Riot” (Lecture, Barnard College, New York, 16 November 2011), zines.barnard.edu/meetmeattheraceriot/video.

Red Chidgeyis a Teaching Fellow at the Centre for Culture, Media and Creative Industries, King’s College London. Her PhD examined the mobilization of feminist memory assemblages in the UK, focusing on the intersections of media, memory, and archives in digital times. Red’s work has been published in Feminist Media Studies, n.paradoxa, and Transform! European Journal of Alternative Thinking and Political Dialogue, and she blogs about her research interests at http://feministmemory.wordpress.com.