Owning A Future/Past Elsewhere: On Special Features

Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 9:43PM

Saturday, November 14, 2015 at 9:43PM Carter Moulton

[ PDF Version ]

I

Over the past few years, film and media scholars have wrestled with the implications of cinema’s migration to the online “cloud.” On top of necessitating a careful re-consideration of cinema distribution, spectatorship, and exhibition practices, instant streaming services and online marketplaces such as Netflix, iTunes, Amazon, and Hulu have made us question the concept of video ownership. These digital libraries, when coupled with services such as Flixster’s Disc-to-Digital—wherein purchased DVDs and Blu-Rays can be uploaded and transformed into UltraViolet copies—suggest that the rows of discs on our bookshelves no longer provide us with a sufficient sense of ownership. As a quick scan of home video distribution reveals, though, cinema’s ascension to the cloud is far from total. In fact, this shift to an immaterial model of ownership is problematized by the curious fact that many of today’s “standard edition” releases actually contain more physical discs than the “special editions” of old.

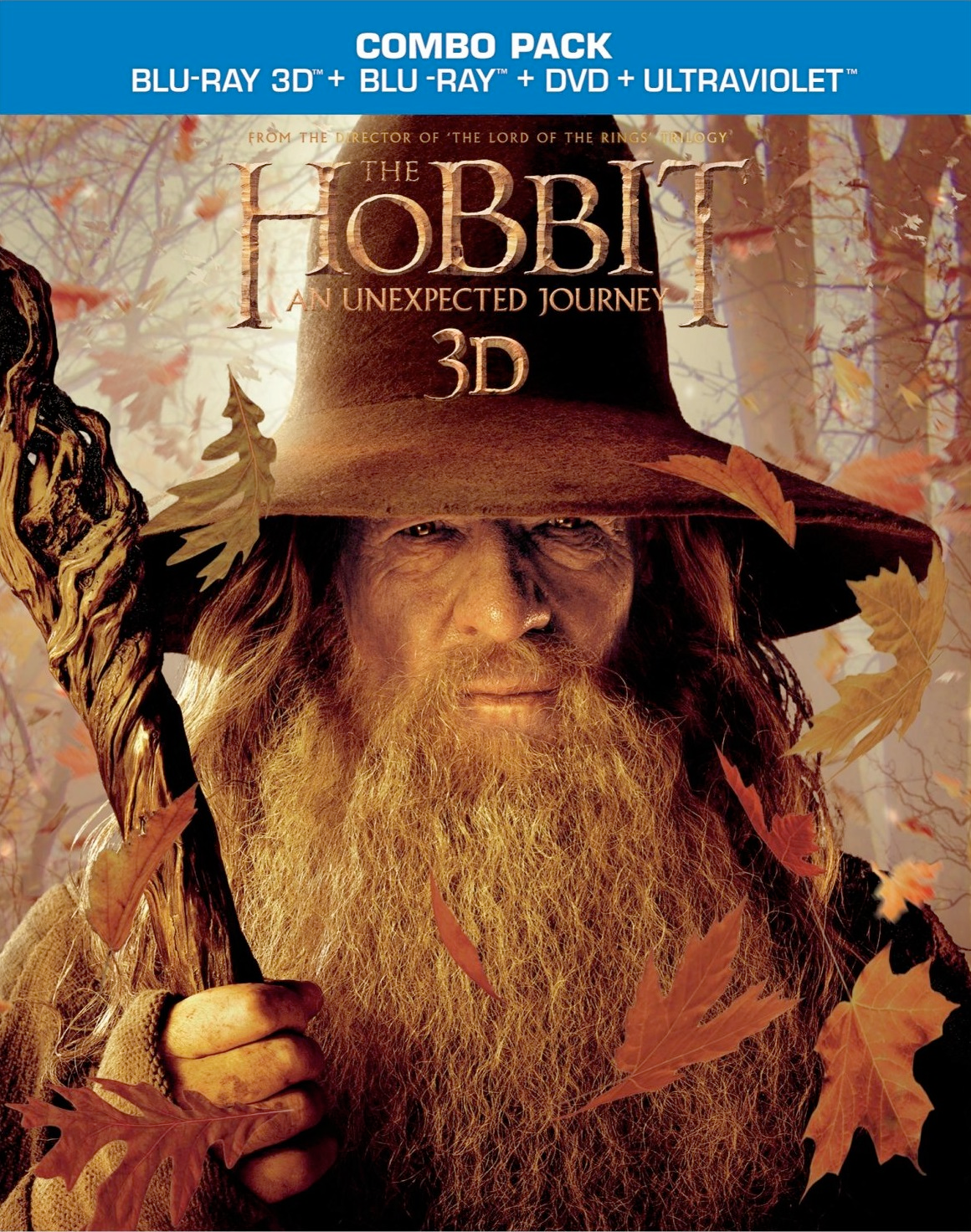

Consider the five-disc standard edition of The Hobbit: an Unexpected Journey, which was released on March 19, 2013. In addition to being released as a digital download in numerous online marketplaces, The Hobbit was rolled out in six different packages, among them a 3D Blu-Ray Combo Pack, a 2D Blu-Ray Combo Pack, and a 2-disc Special Edition DVD. Just as contemporary exhibition practices promote a variety of ways to “see” a movie through 3D, IMAX, D-Box, and High-Frame-Rate technologies, these various discs, drives, pixels, and passwords which constitute current home cinema entertainment emphasize a multiplicity of ways to “own” a movie. Such multiplicities invite consumers to maximize their ownership by purchasing all available formats—since choosing one format means missing out on another. Under this distribution model, an extensive package like The Hobbit 3D Blu-Ray Combo Pack allows fans to sleep softly, knowing that Peter Jackson’s interpretation of Middle Earth rests safely on the shelf, on the hard-drive, and in the cloud.

The Hobbit 3D Blu-Ray Combo Pack

These multiple formats and packages hint at a temporal elongation and spatial expansion of the contemporary cinematic experience. Richard Grusin observes this expansion in 2006, using the term cinema of interactions to describe the “hybrid network of media forms and practices” that makeup the contemporary cinema.[1] For Grusin, the cinema of interactions is a “distributed form of cinema, which demands us to rethink the cinema as an object of study and analysis, to recognize that a film does not end after its closing credits, but rather continues beyond the theater to the DVD, the video game, the soundtrack, the websites, and so forth.”[2] Similar concepts, such as Henry Jenkins’s transmedia and Leon Gurevitch’s cinemas of transactions theorize contemporary cinema as a distributed network and thus highlight the importance of examining the extra- and intertextual forms that condition our anticipation, reception, and overall understanding of cinematic texts. Jonathan Gray mobilizes the term paratext to describe these secondary materials which surround a filmic text. He divides them into two categories: entryway paratexts, “those that control and determine our entrance to a text”; and in medias res paratexts, “those that inflect or redirect the text [during or] following initial interaction.”[3] Gray reminds us that paratexts have “considerable power to amplify, reduce, erase, or add meaning” to the world’s textuality.[4] When we watch a movie trailer or read early reviews but decide not to see the movie, we conflate paratextuality with the text itself by assuming that the film is not worth our time.

Positing today’s cinema of interactions, in which textual meaning and experience is distributed across space, material, information, and time, this article examines cinema’s second disc: special features. This is a direct attempt to answer Gray’s call that scholars should “pay more attention to paratexts and particularly DVDs and bonus materials, to see what meanings the producers are adding to the text, and by extension, to see what role the DVD plays in actually constructing the text as a meaningful object.”[5] I choose to focus primarily on making-of documentaries (MODs), which have been called the central extras on DVDs and Blu-Rays.[6] Using Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit as a case study, I argue that MODs are now being decentralized from the disc and distributed across multiple media in multiple temporalities. Central to this repurposing or remediation (to follow Jay David Bolter and Grusin) of MODs is the mobilization of their pre-textual, promotional value. With the help of scholars such as Gurevitch and P. David Marshall, I suggest that we can now conceptualize today’s cinema as an extrapolation of Lisa Kernan’s work on movie trailers, as a cinema of coming attractions, a time-space in which one is always looking forward and never quite finished—a cinema where promotional forms are not only commodified but also constructed into spectatorial and cultural events.

II

Although some scholars have suggested that DVD extras are “bygones,” the tale of “the death of special features” is quite misleading.[7] True, instantly streamed, ripped, torrented, and rented cinemas are indeed stripping bonus content from their respective films; yet, we must not overlook the fact that the internet, and specifically YouTube, is overflowing with deleted scenes, featurettes, bloopers, and other bonus material. Though this content frequently emerges and disappears as studios engage in tug of war with fans and uploaders, this sprinkling of special features throughout the web illuminates that bonus materials are not being erased from the cinema experience; rather, they continue to circulate as forms of what Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green call spreadable media—content which moves through “an emerging hybrid model of circulation, where a mix of top-down and bottom-up forces determine how material is shared across and among cultures in far more participatory (and messier) ways.”[8] To think about this changing role of DVD extras, I turn to the special features included in purchased physical and digital copies of The Hobbit.[9]

Because of the behind-the-scenes nature of MODs, many scholars, including Craig Hight and Gray, have examined them as “after-the-scenes” paratexts which “stack” layers of meaning onto the text and imbue it with a sense of auteurism, nostalgia, and aura.[10] Unfortunately, these “after-the-scenes” examinations of MODs fail to delineate The Hobbit’s production videos, which were specifically constructed as entryway paratexts, as “before-the-scenes.” Beginning on April 14, 2011, these video blogs were released every so often onto Jackson’s Facebook page leading up to the film’s theatrical release on December 14, 2012. As Hight notes, these pre-textual MODs are often part of an electronic press kit (EPK): “In the guise of presenting a production narrative, such texts in fact serve as extended trailers with their release timed to coincide with that of the feature film they document.”[11]

A simple shift in temporality, from post-text to pre-text, has major implications for the content of MODs. As Hight notes, EPK versions of MODs feature:

...no doubts voiced about the creative or (potential) commercial success of the film, no evidence of tensions (creative or otherwise) in its production, little if any exploration of the wider political economic contexts of its production—in fact, nothing that would disrupt the corporate agenda of the studio that owns the film.[12]

Indeed, the Hobbit production blogs follow these guidelines, always relaying a confident, unified, happy message to Ringers (fans of the Tolkien universe). We can build on Hight’s observations by examining how these blogs continually make known and redraw the parameters of accessibility and exclusivity. Through a careful modulation of textual peeling, pre-textual MODs lay breadcrumbs of information that guide viewers along a very specific path to the text.

In the first video blog, we see Jackson ascending some stairs on his way to the wardrobe department. He speaks to the camera: “We’re having a look at a couple of dwarf wardrobe and make-up fittings... Not that we’ll show you much in this particular blog, because we’ll save that for the future...”[13] He then enters a room in which the walls, covered from floor to ceiling in concept art, are entirely blurred. Jackson sits in what is literally a hazy, half-rendered space—a space that invites speculation and adds the project’s mystique. This half-rendered room provides a fitting metaphor for pre-textual MODs, which, far from providing a “complete” narrative, consciously tease their viewership. In another blog, Jackson literalizes this tension between “inside” access and textual protection by driving through a security checkpoint at Stone Street Studios, where much of The Hobbit was filmed: “The public obviously aren’t allowed in here while we’re shooting, but we thought it would be great to give you all a private little tour around the world of The Hobbit, here at Stone Street [Studios].”[14] With millions of views, it’s safe to say there is nothing “private” about these blogs; but, the idea here is that Jackson is allowing us, some his most trusted viewers, into a world of carefully controlled inside information. Rather than stacking layers onto the text, these production blogs function by slowly peeling and revealing layers of textual meaning. This strategy serves the cinema of interactions, where “the future, not the past, is the object of mediation—where the photographic basis of film and its remediation of the past gives way to the premediation of the future.”[15]

Clip from Peter Jackson’s Hobbit Video Blog

Returning to our list of The Hobbit’s special features, we can now see that all of the disc’s materials were constructed as pre-texts, as premediations of either the film itself or a related attraction. The online spreading of these entryway pre-texts is central to the goal of premeditation and event construction, which explains why all of these special features premiered on YouTube or Facebook. Rather than claiming that bonus material is being stripped from the DVD, we should consider the ways that bonus discs are plucking and recycling content from digital space. Each piece of bonus material included in The Hobbit theatrical edition DVD/Blu-Ray advertises a product that had been available months before the film’s home-video release. Consequently, The Hobbit’s bonus disc is nothing more than a curation of promotional forms of the past—far from enriching the text, these materials ask us to look elsewhere, either to digital space, to New Zealand, or to a future that has already arrived.

These issues of time are central to understanding today’s cinema. Because most DVD bonus content is either being released into or circulating through a vast pool of online space, the question shifts from “where can I get it?” to “when can I get it?” Put in Paul Lunenfeld’s words, the internet brings with it an “explosion of access,” a world where “anything can be obtained but nothing is special.”[16] In order to construct specialness and eventfulness, industry practices have begun to intensify and manipulate the temporality of today’s distributed cinema experience. To explore this, the next section shifts to an as-of-yet-unmentioned special feature that accompanied purchases of The Hobbit standard edition: a “live” worldwide digital sneak peek of The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug.

III

Purchasers of The Hobbit received a twelve-digit UltraViolet code, which allowed them to access a cloud copy of the film. This code, however, could also be entered at thehobbit.com/sneak on March 24, 2013, to access a “worldwide live event hosted by Peter Jackson.” Leading up to the film’s Blu-Ray release, television ads promoted this event with a hearty offscreen voice: “Own The Hobbit and you can join a worldwide live event hosted by Peter Jackson in which he will reveal a first look at the next movie in the Hobbit Trilogy. This exclusive live event can only be seen one way: you must own The Hobbit.”

Television Ad for The Hobbit Blu-Ray Release

The length and specific contents of this “event” were kept under wraps, which propelled speculation on fan blogs and message boards—some even put their codes up for sale. This twelve-digit code serves a double function, as both a gateway to a film and an advertisement for a future film. Leon Gurevitch reminds us that the commodification of promotional texts extends back to early cinema, in which advertisements such as “Dewars Scotch Whisky” (1898) were heavily attended public screenings. “Crucially,” he writes, “these adverts were promotional at the same time as they were attractions to be viewed for general entertainment.”[17] Yet, Gurevitch and scholars such as P. David Marshall suggest that the commodification of promotional forms is being intensified. Marshall writes that there is “more promotional material produced about any given cultural product than previously” and that the lines between product and promotion are often blurred.[18] This is obvious when fans attend movies solely on the premise of seeing another film’s theatrical trailer (seeing Secondhand Lions in order to access a trailer for The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King, for instance). In our case, though, a simple twelve-digit code signifies the conflation of the product and its promotional form. To own one is to preview another.

The Hobbit’s Worldwide Live Event Landing Page

When the big day arrived, I entered my code and accessed a screen, which asked me to select my home country from a grid of about twenty countries. Such an interface, with rows of country flags underneath a banner which reads “Worldwide Live Event,” drops the viewer into a space that can only be imagined, unknowable in size and limitless in scope. Entry into this imagined space is made possible through a temporally-constricted window of access, whereby tuning in “live” means experiencing sensations of exclusivity, privilege, and in turn, power. Of course, this particular spectatorial space was much smaller than imagined, since the event was broadcast in English only and not offered in all viewing markets. Fifty-five minutes in length, the sneak peek functioned similarly to the ten-minute blogs discussed earlier, with snippets of unfinished footage, insight into Jackson’s artistic vision, and tidbits of narrative information, all shrouded in the atmosphere of secrecy and exclusivity typical of pre-textual MODs. (At one point, Jackson whispers to the camera: “You didn’t really think we were going to show you Smaug did you?”) Yet, because of the event’s live broadcast aesthetic, viewers could hold out hope for an accidental glimpse at concept art or precious footage. In fact, there are a few rather amusing moments during the broadcast when Jackson attempts to cover pictures and screens with his body.

Clip from The Hobbit’s Worldwide Live Event

This liveness fulfills Charles Acland’s suggestion from 2003 that “a sense of immediacy and ‘liveness’ of performance” will be added to cinemagoing in the digital age.[19] By centralizing real time and screen space—only one time to see it, in only one digital space to view it—and marking this spatiotemporal formation with a sense of interactivity, this sneak peek remediates certain aesthetics of the television special, the call-in telethon, and the breaking news report—complete with a scrolling Twitter ticker along the bottom of the video. These remediated forms of liveness and urgency are then molded into the framework of MODs and theatrical trailers. As an amalgam of pre-existing media and exhibition practices, this sneak peek constitutes a cinematic event because of both its constructed, promoted nature and its distinction from everyday internet use. Through the liveness of real time, a fleeting digital moment, an imagined and distributed space of viewing, and a centralization of digital space, the internet’s “archive” is made “live.”

IV

Owning a cinematic text today involves a “combo” of material, immaterial, and numerical forms. Additionally, I have suggested an increasing temporal shift of the DVD MOD from a “timeless” post-text to a well-timed entryway paratext—a shift made possible by its spreadable circulation through digital space. In the case of The Hobbit, this leads to a “behind-the-scenes” feature which consciously “hides the scenes.” A quick survey of other MODs found on standard-edition special-features discs illustrates further the recycling and re-packaging of promotional forms originally created to make “announcing gestures” and frame the film as a distinct event. A Les Misérables featurette focuses on the musical’s “live-singing” aesthetic: “This is the first time anyone’s ever tried it like this… This has not been done... in a musical before.” An EPK highlights Anna Karenina’s unique set design: “The rules of the period film have been completely broken… This is taking style to a whole new level.”[20] And countless IMAX featurettes (Oblivion, Prometheus, Skyfall, Interstellar, The Dark Knight, etc.) explain why theatergoers should spend the extra money to view it as it was “meant to be viewed.”[21] Today’s distribution practices work to intensify the two-tier marketing practice, with standard editions recycling and re-packaging forms of spreadable pre-texts, and special editions becoming more centralized “Works of Art”—as evidenced by the 31-disc Harry Potter box set which comes in a limited-edition collector’s “trunk” and the 10-disc Marvel Universe collection which comes in a “top-secret” suitcase.

As scholars, we should more carefully consider the temporal relation between paratext and text. Such an approach allows us to question Hight’s claims that MODs do not lead to “a collapse of our sense of disbelief in the film’s narrative.”[22] This is certainly true for in medias res MODs, but we are ignoring the power of the Kuleshov effect if we suggest that this re-ordering of textual relations does not re-shape meaning and reception. Might there exist a correlation between Jackson’s pre-textual production blogs—which contain uncountable images of green screens, artificial lighting, and computer modeling—and a demystification of the text? Upon release, many viewers criticized the film for its overly artificial, videogame aesthetics. A.O. Scott described the film’s battle sequences as “masses of roaring, rampaging pixels,” ultimately concluding that the film was merely a “high-definition tourist attraction.”[23]

Movies are only one of the many “tourist attractions” on the horizon in today’s cinema. As promotional material is commodified, remediated, and re-commodified, today’s digital distribution and marketing practices take place within a system we might call the cinema of coming attractions, Lisa Kernan’s phrase to describe movie trailers, which emphasize that “the pure cinema event is... sensed as never present, but always coming.”[24] When extrapolated, the cinema of coming attractions hearkens back to Tom Gunning’s cinema of attractions and the commodified promotional forms of early cinema while also describing the temporally elongated and spatially distributed nature of cinema systems today. Elsewhere I have examined this phenomenon as it relates to cinemagoing as a cultural practice.[25] This notion of a cinema of coming attractions does not discredit or overshadow other “cinema(s) of” theorizations—indeed, Grusin is right to suggest that it is now “more accurate to consider the theatrical release as the second-order phenomenon,” as only “one element of the distributed cinematic artifact” [26]—but reaches in a very specific direction so as to delineate a culture of promotional peeling and recycling. In such a system—and as evidenced by special features discs which ask us to look away from the text and to a future or past elsewhere—the promotion is the product; the film gives way to its premediation, but more specifically to the spreadable entryway paratext, the promotional form—the theatrical trailer release, the making-of documentary, the soundtrack release, the early review, the digital sneak-peek, the viral campaign, the advance-ticket sale, and the long line that reaches around the theater.

Notes

[1] Richard Grusin, “DVDs, Video Games, and the Cinema of Interactions,” Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies 51 (July 2006): 71.

[2] Grusin, “Cinema of Interactions,” 76.

[3] Jonathan Gray, Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts (New York: NYU Press, 2010): 23, 35.

[4] Gray, Show Sold Separately, 46.

[5] Craig Hight, “Making-of Documentaries on DVD: The Lord of the Rings Trilogy and Special Editions,” The Velvet Light Trap 56 (Fall 2005): 5.

[6] Hight, “Making-of Documentaries on DVD,” 5.

[7] Peter Dean, “DVDs Add-Ons or Bygones?” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 13.2 (2007): 120–22.

[8] Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford and Joshua Green, Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture (New York: NYU Press, 2013): 1.

[9] The Hobbit: an Unexpected Journey. Blu-Ray. Directed by Peter Jackson, 2012.

[10] Jonathan Gray, “Bonus Material: The DVD Layering of The Lord of the Rings,” The Lord of the Rings: Popular Culture in Global Context, ed. Ernest Mathijs (London: Wallflower Press, 2006), 242; Robert Alan Brookey and Robert Westerfelhaus, “The Digital Auteur: Branding Identity on the Monsters, Inc. DVD,” Western Journal of Communication 69, no, 2 (2005): 115–119.

[11] Hight, “Making-of Documentaries on DVD,” 7.

[12] Hight, “Making-of Documentaries on DVD,” 7.

[13] Peter Jackson, “The Hobbit Production Blog #1,” Facebook, 14 April 2011, on.fb.me/11MtHoP.

[14] Peter Jackson, “The Hobbit Production Blog #7,” Facebook, 6 June 2012, on.fb.me/15QC07j.

[15] Grusin, “Cinema of Interactions,” 75.

[16] Peter Lunenfeld, “The Myths of Interactive Cinema,” Narrative Across Media: The Languages of Storytelling (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2004): 386.

[17] Leon Gurevitch, “The Cinemas of Transactions: The Exchangeable Currency of the Digital Attraction,” Television & New Media 11, no. 5 (2010): 369.

[18] P. David Marshall, “The New Intertextual Commodity,” The New Media Book, ed. Dan Harries (London: BFI, 2002): 71.

[19] Charles Acland, Screen Traffic: Movies, Multiplexes, and Global Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003): 222.

[20] “Anna Karenina—Creating the Extraordinary World of Anna Karenina Featurette,” YouTube, 4 December 2012, youtu.be/MSmPXiGVjnI.

[21] “Oblivion - IMAX Behind the Scenes Featurette,” Youtube, 3 April 2013, youtu.be/VQcgiZwLxVM.

[22] Hight, “Making-of Documentaries on DVD,” 14.

[23] A.O. Scott, “Bilbo Begins His Ring Cycle: The Hobbit: an Unexpected Journey,” The New York Times, 13 December 2012, nyti.ms/SkfkXA.

[24] Lisa Kernan, Coming Attractions: Reading American Movie Trailers (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2004): 24.

[25] Carter Moulton, “Midnight in Middle Earth: Blockbusters and Opening-Night Culture,” New Review of Film and Television Studies 12, no. 4 (2014).

[26] Grusin, “Cinema of Interactions,” 73, 80.

Carter Moulton is currently serving as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Thailand and will pursue a PhD in Screen Cultures at Northwestern University in Fall 2016. He received his master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where he researched movie audiences, cinemagoing, silent cinema, and emerging technologies in film production, distribution, and exhibition. His work has appeared in CineAction, The New Review of Film & Television Studies, and Media Fields Journal.