Looking into the Desert Mirage

Monday, December 11, 2023 at 7:49PM

Monday, December 11, 2023 at 7:49PM Daniel Mann

[ PDF Version ]

One hot morning in 1799, Gaspard Monge, Napoleon’s official mathematician, wandered into the desert around Alexandria to survey the battlefield. Looking into the open terrain, he was suddenly struck by a frightening image. A spectacle of a standard inferior mirage in the form of a body of freshwater materialized and quickly vanished upon his approach. Recalling this moment of terror in his Mémoires sur l’Égypte (1800), Monge described marching through the desert between Alexandria and Cairo and being overwhelmed with the daily appearance of optical illusions. “The land was terminated,” he wrote, “by a general inundation, turning villages into islands.”[1] In his anxious observations, he associated the desert ecology with a danger zone, wherein vision is impaired and illusive. Monge called this desert illusion “mirage,” derived from the French word marari (to wonder). Notably, he associated the mirage with an experience of being alone in a vast, barren terrain.

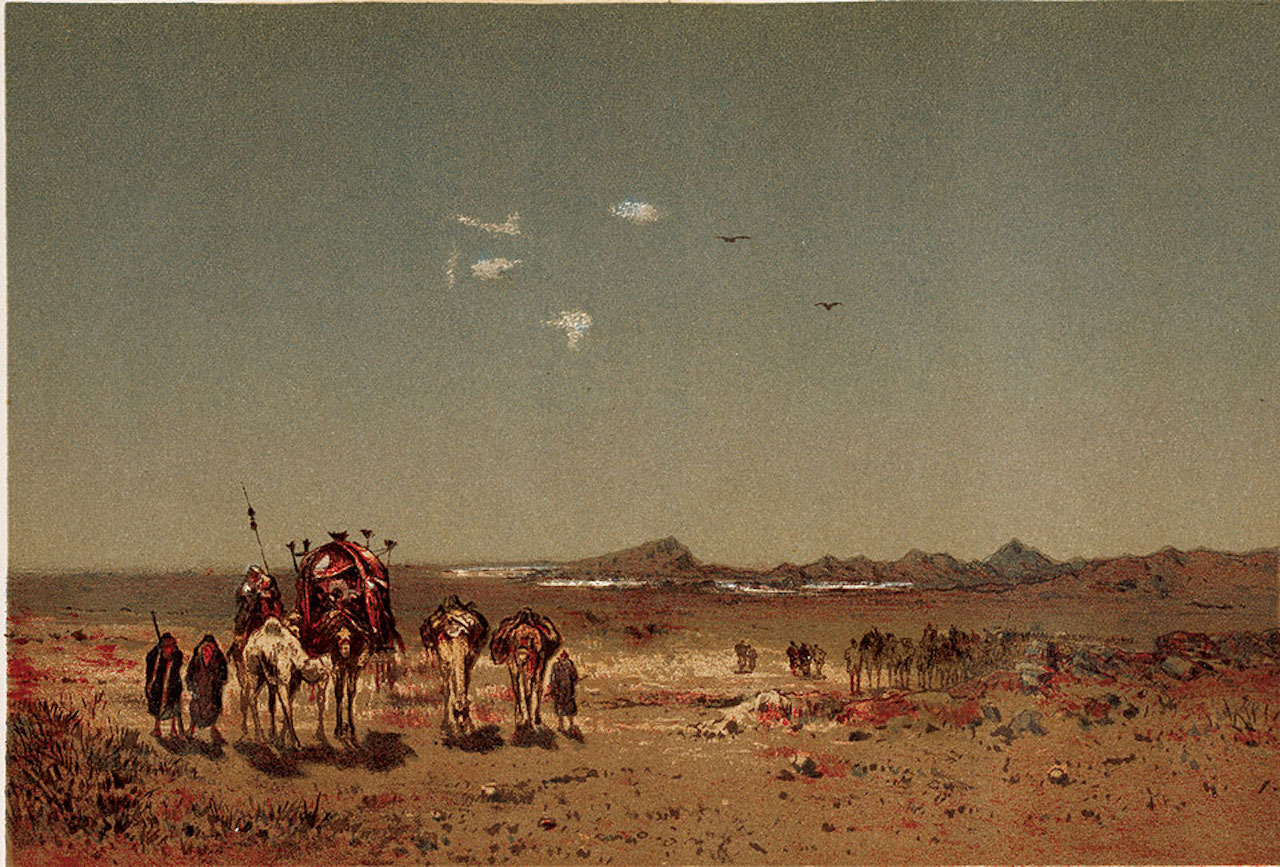

Figure 1. A mirage in the desert, from Camille Flammarion, L’Atmosphere (Paris, 1873).

Monge’s hallucinations are symptomatic of colonial blindness that refuses to see the desert in its material existence and locality. The perception of desert environments as inanimate and inhospitable is inextricable from the optical illusions that hover over the hot sand. The vast ecology of the desert becomes a mere screen for orientalist phantasms that flicker and then vanish. Much as British explorers reported seeing ghostly figures rise and fall among the “ice deserts” of the Arctic during their mid-nineteenth-century quest to navigate through the Northern Passage, stories of mirages in the Arabian and Saharan deserts are endemic to a specific imperial disposition that delineates the desert as an ex-territory disconnected from sedentary life, with a peculiar logic, laws, and spirituality.[2]

Colonial tales of desert mirages in Arabia and the Sahara are often disclosed by individual explorers who see themselves reflected in, and diffracted through, sand and ice. In the diaries of men such as Gaspar Monge, T. E. Lawrence, and Richard Francis Burton, hallucinations recast the desert as a space of masculine solitude and romantic individualism. The contrived image of the desert as an empty land engenders, time and again, a horror vacui for white men, where the harsh climate brings them face-to-face with the limits of their subjectivity. A zone of isolation, the desert is rendered in such stories as remote and forsaken.

It is worth reflecting here on the various etymologies of the word “desert.” It comes from the Latin desertum, a translation of the Greek erēmos, which means solitude or the abode of a hermit or ascetic. This etymology exposes the deeply rooted perception of the desert as an ex-territory wherein European men seek spiritual elation. Literary descriptions of the mirage are entwined with the work of fiction, fictionalizing scenes in written accounts (T.E. Lawrence had been accused of inventing and manipulating his stories) of a land that has been pushed into fiction, myths, and fable. Fiction, tales, and myths promoted by British and French men sever the desert from European geography, turning it into a non-place.

Another etymological source ties the desert to the Latin deserere (to abandon or forsake), where one is stranded, alone. The most prevailing fiction is the scientific assertion that desert lands were once fertile and green before being ruined by the pastoral and nomadic ways of life of indigenous people. By advocating the fallacious notion of the desiccation narrative positing a desert that was once verdant forest, colonial scientists advocated the introduction of agriculture and plantation. This was considered essential for the sake of saving “the commons.” Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the notion of agricultural improvement in desert areas advanced the rise of liberal economic thought and promoted the idea that wastelands are simply wasted land. A vilifying narrative of moral failure frequently accompanied arguments in favor of reviving the once flourishing desert, blaming those who misuse and spoil the commons. By the early nineteenth century, fears of encroaching deserts and the waste of good land were being articulated by notable figures in European countries. The influential writer and politician François-René de Chateaubriand, echoing Montesquieu, wrote in 1811 that Palestine had been transformed from a fertile and rich land to a barren and dead country due to war and local invasions by the Arabs.[3] Indeed, the colonial perception of deserts as wastelands are the bedrock of neo-colonial economies that make use of land enclosure and excessive resource extraction.

To counter this notion of wasteland, where apparitions and illusions become inseparable from Eurocentric vision, we must today undo the Euro-American desert imaginaries to reenvisage their role in our collective futures. Considering the rapidly rising temperatures and expanding deserts, we need visualizations of deserts that can resist the violent abstraction sustained through colonial and neo-colonial lenses. Replacing the original meaning of erēmos, we require new ways of making the desert visible and sensible to invite mutual responsibilities for life. Perhaps, in the desert, we can see not only the age-old structures of power and subjugation but also new possibilities of making common. This is where the notion of mutuality becomes key.

But for mutuality and common space to open, we should first trace not only how the colonial mirage arose but also where it continues to expunge the desert and render it a space of war, scarcity, death and solitary struggle. Monge’s mirage is today reincarnated in popular big-budget films that produce special effects in the desert. Remade in the production of recent Hollywood titles such as Dune (dir. Denis Villeneuve, US, 2021), Oppenheimer (dir. Christopher Nolan, US, 2023),Mission to Mars (dir. Brian De Palma, US, 2000), The Martian (dir. Ridley Scott, US, 2015), Last Days on Mars (dir. Ruairi Robinson, Ireland/UK, 2013), The Red Planet (dir. Antony Hoffman, US/Australia, 2000), Transformers (dir. Michael Bay, US, 2007), Game of Thrones (David Benioff and D.B. Weiss, HBO, 2011–2019), Star Wars (dir. George Lucas, US, 1977), Red Planet (dir. Antony Hofmann, US, 2000), Star Trek Beyond (dir. Justin Lin, US 2016) to name a few, mirages are artificially concocted through the use of deserts as backdrops for massive explosions, whether real or realized through CGI. The desert is once again immensely productive for the screen-based industry precisely because there, upon the yellow sand, visual effects can be easily added. “The repetitive and smooth terrain of the desert make it a perfect canvas for applying layers of visual effects,” notes a special effects specialist who worked on The Martian. “That is,” the specialist continues, “if you can afford replacing the deserts of south California with the Middle East and to render them as Mars.”[4] White men–Matt Damon, Timothée Chalamet, Tim Robbins, Val Kilmer etc.—are again cast into the desert to struggle with hostile environments. Solitude is a prerequisite.

Economic free zones and militarized spaces lure Hollywood film producers to neo-colonial desert places in Jordan, Morocco, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which are then captured and inserted into green screens behind anthropogenic stories about the planetary frontier. Designed to cater only to ultra-rich film companies, land use laws and tax rebates in the Middle East and North Africa lubricate a neo-colonial configuration that offers the desert as a resource to exploit. If the frontiers of the nineteenth century no longer serve the imagination of a European explorer, planetary frontiers are carefully fashioned to revive the dream. Monge’s mirage is repackaged as a multimillion-dollar movie.

Figure 2. Salar de Uyuni salt flat in Bolivia appears in the 2017 film Star Wars: Episode VIII - The Last Jedi. Photo: Lucasfilm/ Entertainment Pictures

Of course, using deserts as backdrops for frontier narratives of struggle and solitude is hardly new. From 1910 onwards, the rapidly growing Hollywood film industry marked the desert in the Southwest of the United States as an ideal landscape for filmmaking. Hollywood’s attention bolstered the national imagination of the West as an unspoiled wilderness, thereby concealing all traces of the indigenous people inhabiting this land. At the same time, with its long hours of daylight, consistent weather, and, most importantly, a terrain that could serve as a backdrop for diverse narratives, from Westerns to science fiction, the desert climate and geology were uniquely suited to the needs of the motion picture industry.[5]

A unique and paradoxical optical logic thus links cinematic spectacle and the desert, where the cameras of big-budget films capture arid lands as representations while simultaneously partaking in a much more pervasive process of abstraction that extends the colonial perception of tabula rasa. Visual spectacle is, after all, a form of geographical abstraction. Film theorist Hunter Vaughn writes that “(S)pectacle in Hollywood films, distracts the viewer from the material reality of its making—including the resources used, the natural beings affected, and the waste produced.”[6] The optical mirages in Hollywood blockbusters—and in particular, the spectacle of destruction so often rehearsed in the desert—channel the desire to escape the real by destroying it in full view. The cinematic depiction of planetary crisis and individualistic struggles to survive thereby impede questions concerning territorial expansion in the form of (neo) colonization and imperialism that continue to sustain resource capture and extractive capitalism. The desert, in that sense, is a screen.

Importantly, while Western visualities continue to demarcate the desert as a space of solitary struggle, they also erase bodies that do not fit this narrative. The radical overexposure of desert surfaces is inseparable from the abstraction of placeness through imperial literary and cinematic lenses. Governments and private companies expose the bodies of humans and nonhumans in the desert to advance an oppressive visual regime which utilizes the land as a sandbox for techno-militarism. Jason de Leon, for instance, has documented migration through the Sonora Desert across the hostile terrain of the mountains by collecting material evidence of migrants making the routes. For de Leon, the desert is an active agent within what he calls the “hybrid collectif” that makes up the brutal deterrence policies practiced by the US border patrol. “Nature, in the Border Patrol’s disinfected public discourse,” he writes, “is a runaway train that has no conductor.”[7] By wielding the desert as a weapon, the US Border Patrol can shed responsibility for the death of migrants in the brutal terrain. In de Leon’s anthropology of border crossing, the desert registers human activities on its surface with amplified accuracy. “In the desert,” he observes, “nothing is completely erased.”[8]

In Israel-Palestine, the desert is similarly used as a weapon for land confiscation and militarization. The systemic nationalizing of land is executed under an ideological doctrine that regards the desert as empty and barren. Large swathes of the desert are declared closed military zones with the unofficial purpose of cutting off Palestinians and Bedouins living below the aridity line from neighboring towns and villages in Palestine. Construction of Palestinian homes, as well as movements of civilians, are easily monitored, regulated, and banned to maintain the perception of the land as vacant and, therefore, up for grabs. Spatial theorist Eyal Weizman suggests that the lucid visibility of the Naqab desert is inseparable from the climate and must be understood through the inverse relation between humidity and visibility. “The further south one flies,” writes Weizman, “the drier the air and the thinner and more conducive to vision it becomes.”[9] Satellite imagery that captures the desert is thus able to detect very fine details, including delicate marks ingrained in the geological strata.

As a space that inscribes lucid vision, the desert invokes metaphors of seamlessness and uninterrupted communication. Paul Virilio famously reflected on the sheer real-time visibility of the US military’s violent 1991 aerial assault on Iraqi soil. “The audio-visual landscape,” Virilio writes in Desert Screen, “becomes a landscape of war and the screen a square horizon, overexposed with video salvos, like the field of battle under the fire of missiles.”[10] Explaining the title of his essay, he remarks that “the screen is the site of projection of the light of images—mirages of the geographic desert like those of the cinema.”[11] Virilio has frequently emphasized the role of the desert frontier or glacis, the no-man’s-land surrounding the empire, which becomes the object of the emperor’s gaze as a field of military vision. Thus, overexposure of the desert environment must not be couched as the opposite of abstraction but its flipside. It is yet another mode of obliterating the essential circumstances for life and facilitating the destruction of indigenous lifeworlds. The hypervisibility of the desert, as Virilio intimates, is another kind of mirage, not the illusive illusion of an uncanny presence but the equally spectral and fictional absence of life. In this mirage, visual technologies are deployed to serve the colonial desire to “see too much” as another mode of erasure.

Perhaps the most pronounced iteration of overexposure has been the flashing light of the hundreds of nuclear explosions in the deserts of the United States, Kazakhstan, Algeria, and the Arctic. As famously suggested by Akira Mizuta Lippit, such atomic blasts are akin to massive cameras that sear organic and nonorganic matter to leave photograms of destruction: “images formed by the direct exposure of objects on photographic surfaces.”[12] In this modus of overexposure, the desert becomes a photosensitive surface that bears the marks of the instant flash. In this instance, extreme visibility is a form of erasure, while the longue durée of radioactivity lingers in geological strata, and the desert is turned into a vast laboratory of nuclear effects wherein all life forms are enlisted as test subjects.[13] The exploitation of the desert as a space for techno-military experimentation ties security and cinema together as two ultra-wealthy industries that thrive on arid lands as an exteriority, a planetary backlot, an excess wasteland, to be used and abused.

Residues scattered across the surface of the desert are doleful reminders of the irreversible environmental damage wrought by Euro-American colonialism. A closer examination of the surface of desert film locations might lay bare the violence enacted within, whether it be the abandoned belonging of migrants in the Sonoran desert, ruins of Bedouin villages in the Naqab, ISIS camps in Tunisia, or the radioactive waste that saturates large swathes of the desert in Nevada and Utah, including the iconic Monument Valley.[14] That same surface that has been rendered smooth, generic, empty, and barren through the eyes of (neo)colonialists is today an archive that stores various violent incidents. Between the systematic abstraction of locality and placeness, and the inherent capacity of the desert to preserve, desert spaces are unique geographies through which we reimagine the deep past or far future. Within the more protracted temporalities of geology, which escape the lenses of cameras, the desert becomes the emblematic space of our common future existence. Fluctuating between the spectacular hallucinations that conceal the desert geography, and the forensic scrutiny of governments and private security companies that subject it to extreme transparency, we are called to carve new ways of seeing that are detached from the extractive desires of colonial and neo-colonial visualities.

A revised vision of the desert should not simply strive to dispel the mirage as a way of re-territorializing places and engaging more directly with the real. Instead, the desert invites us to hallucinate, speculate, and reimagine a new sense of mutual belonging to a shared space—or, more accurately, a shared loss of locality and belonging. It is the emblematic space for our mutual impasse in confronting a shared future. Philosopher Jacques Derrida once suggested that “the desert is a paradoxical figure of the aporia,” an impasse suggesting both the loss of a defined sense of place and the possibility of signifying place as such.[15] For Derrida, the desert is where we begin to search for a new and mutual being. In the desert, he writes, “there is no marked out or assured passage, no route in any case, at the very most trails that are not reliable ways, the paths are not yet cleared, unless the sand has already re-covered them.” Still, Derrida asks, “isn’t the uncleared way also the condition of decision or event, which consists in opening the way, in (sur)passing, thus in going beyond?”[16] Perhaps the path to mutuality and commonality goes through the desert, the ground zero of geographical abstraction and coloniality. It could be that we need a new “desert cinema” to reveal our common existence and mutual dependency on the environment. Cinema, after all, could be defined as a collective desert mirage necessary for the sake of experiencing, imagining, and shaping together a new sensibility to Earth.

Notes

[1] Christopher Pinney, The Waterless Sea: A Curious History of Mirages (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018).

[2] Shane Mccorristine wrote on the spectral visions seen by British colonialists in the mid- and late-nineteenth century, linking the eerie vision to the horror vacui evoked by the barren land and the tabula rasa made of the Arctic at the expense of its indigenous Inuk inhabitants. Shane Mccorristine, The Spectral Arctic: A History of Dreams and Hosts in Polar Exploration (UCL Press, 2018).

[3] Diana K. Davis. The Arid Lands: History, Power, Knowledge (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 75.

[4] Daniel Mann, “Red Planets: Cinema, Deserts and Extraction,” Afterimage 49, no. 1, 2022.

[5] See Brian R. Jacobson, Studios Before the System: Architecture, Technology, and the Emergence of Cinematic Space (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015); Jennifer Peterson, “The Silent Screen 1895–1927,” in Hollywood on Location: An Industry History, ed. Joshua Gleich and Lawrence Webb (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2019).16-44.

[6] Hunter Vaughn, Hollywood’s Dirtiest Secret: The Hidden Environmental Costs of the Movies (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 42.

[7] Jason De Leon, The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2015), 39–43.

[8] De Leon, The Land of Open Graves, 39–43.

[9] Eyal Weizman and Fazal Sheikh, The Conflict Shoreline: Colonization as Climate Change in the Negev Desert (Brooklyn, NY: Steidl/Cabinet Books, 2015), 7.

[10] Paul Virilio, Desert Screen: War at the Speed of Light (New York: The Anathole Press, 2002) 17.

[11] Virilio, Desert Screen, 17.

[12] Akira Lippit Mizuta, Atomic Light (Shadow Optics) (University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 68.

[13] Jennifer Fay, Inhospitable World: Cinema in the Time of the Anthropocene (Oxford University Press, 2018), 64.

[14] Today scientists understand the extent of the threats posed by the above-ground testing of nuclear weapons in the region. At the time, the Nevada Test Site was chosen as a “safe” site to conduct this kind of testing since it was assumed that winds would blow “radiological hazards” away from the population centers of Las Vegas and Los Angeles. They did, in fact, do so, sending huge toxic plumes of radioactive dust across the stony valleys and canyons of southern Utah and northern Arizona, some of Hollywood’s most popular film locations.

[15] Jacques Derrida, On the Name, ed. Thomas Dutoit, trans. David Wood, John P. Leavey, Jr., and Ian McLeod (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995), 53.

[16] Derrida quoted in Aidan Tynan, The Desert in Modern Literature and Philosophy: Wasteland Aesthetics (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2020), 87.

Daniel Mann is a writer, filmmaker and lecturer at the Film Studies department at Queen Mary, University of London. He is the author of Occupying Habits: Everyday Media as Warfare in Israel-Palestine (Bloomsbury, 2022), and of articles and essays in journals such as Media, Culture & Society, Screen, Social Text, World Records, and Afterimage. Mann’s films were screened at various festivals such as The Berlinale, Rotterdam and Cinéma du Réel.