Industrial Strength Queer: Club Fuck! and the Reorientation of Desire

Thursday, December 5, 2013 at 7:02PM

Thursday, December 5, 2013 at 7:02PM Bhaskar Sarkar

[ PDF Version ]

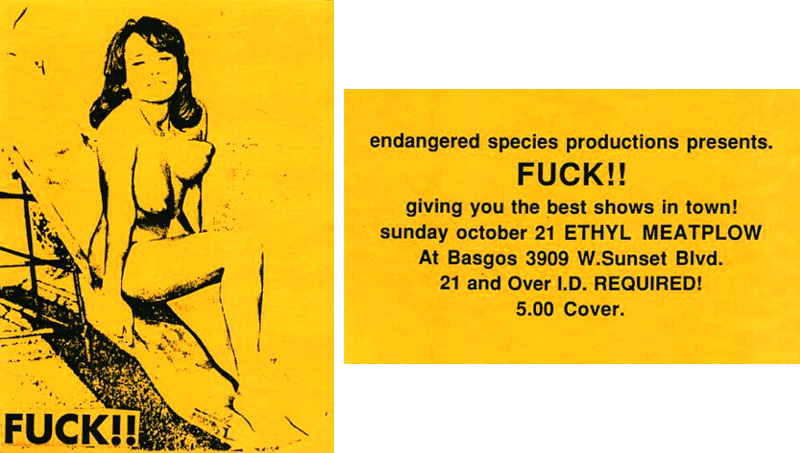

Figure 1: Club Fuck! publicity flyer, early 1990.

“The Best Fuck in Town”

The research for this essay began in my garage, a space that bears the brunt of my packrat obsessions. As I dusted off and opened a box of club-land memorabilia dating back two decades, a rush of allergies and nostalgia swept over me. Sifting through the flyers, advertisements, and such related to the legendary Club Fuck!, I was transported instantly to Basgo’s Disco, a sliver of a club wedged between a laundromat and a fast food joint along a rundown strip of Sunset Boulevard in Silverlake. This architecturally unremarkable spot, officially acknowledged since 2008 as a GLBT community landmark, has undergone several name changes and witnessed a whole lot of history.

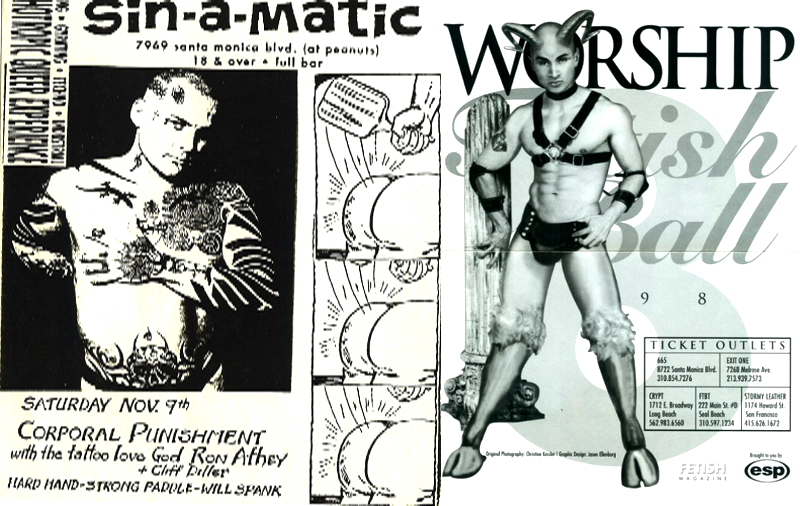

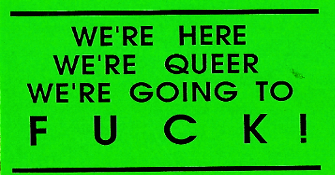

Figure 2: Publicity for Sin-a-Matic (c. 1991) and Fetish Ball (1998).

Once known as the Black Cat, it was the scene of an aggressive police raid on New Year’s Eve, 1966–67, precipitating street protests that heralded the Los Angeles gay rights movement. More recently, the venue was called Le Barcito and was popular for its biweekly drag shows.[1] The 1980s–early 1990s avatar, Basgo’s Disco, was a blue collar, neighborhood latino gay bar; except on Sunday nights between 1989 and 1992, it hosted Club Fuck!—a weekly event combining fetish cultures, performance art, and industrial/tribal dance music—for a markedly different clientele.

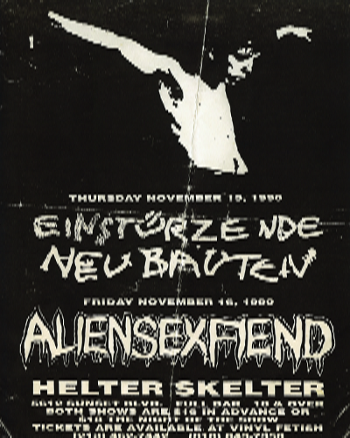

Figure 3: Flyer for Helter Skelter (1990).

Like its sibling events, the Saturday-night club Sin-a-matic for a 18-plus crowd at a swankier venue in West Hollywood or the more sporadic and posh Fetish Ball, Club Fuck! promised a “psychotropic” experience. The three events had much in common in terms of DJs and music, performers and subcultural rituals, and a non-normative, pansexual ethos. But perhaps because it emerged organically from the occasional gatherings of a circle of like-minded people, and because it was a space where scripts and mores tended to careen into the unknown—not to mention its in-your-face name and its “fringe” location—Club Fuck! attained a cult notoriety that the other two never enjoyed. While the dance club aspect was central to the Fuck! experience, clearly something more was at stake in comparison to other popular industrial and trance music clubs of the period, like Helter Skelter or Kontrol Factory.

An early (April 1991) review in the L.A.Weekly makes precisely this point even as it struggles to pin down the enigma of “The Best Fuck in Town” as not simply “an existential exercise in bad attitudes,” but rather “a celebration of the primal life force amped up to overload,” with an “S&M/sexual subtext” that makes it “sociologically fascinating.”[2] Almost two years later, a January 1993 report in the Los Angeles Times titled “Nonconformist Fun” eschews the name of the club altogether, coyly observing that it remains “unprintable in most places without the aid of asterisks and ampersands.”[3] By then, Basgo’s Disco had been closed down by the police on charges of serving liquor to under-age clients, and Fuck! had settled into the more spacious Hollywood venue Dragonfly, and started attracting a more mainstream crowd. When Liza Minnelli turned up one night, many of the club regulars were noticeably starstruck, even though her presence underscored the club’s newfound status as a trendy hotspot. Soon after, in April 1993, an overzealous raid by the LAPD’s Vice unit, involving around thirty cops, ten cars, two fire trucks, and one helicopter, ended Club Fuck! on grounds of obscenity and lewd conduct.

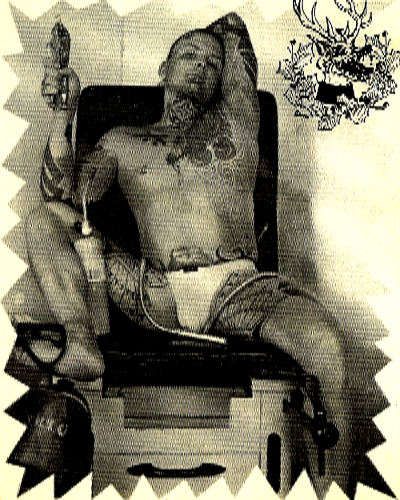

Figure 4: Performance artist Ron Athey on flyer for Sin-a-Matic

Figure 5: Michelle Carr channeling Betty Page. Photo courtesy of the late James Stone.

Fuck! was an assemblage of disparate tendencies and forces: not surprisingly, it pulsated with contradictions. It drew on the part postpunk, part industrial, part tribal music of bands such as KMFDM and The Revolting Cocks, Thrill Kill Cult, and Psychick Warriors ov Gaia; the frenetic energies of Southern California musical acts such as Ethyl Meatplow, Crash Worship, Nervous Gender, Babyland, and Linda LeSabre; the cut-up aesthetic and cyberpunk imaginations of alterna-culture icons such as William Gibson, Brion Gysin, and William Burroughs; subcultures including body manipulation, leather and fetish, S&M, and public space sex;[4] the critical-affective charge of contemporary artists like Karen Finley, Catherine Opie, and David Wojnarowicz, and performance artists such as Ron Athey, Bob Flanagan, and Fakir Musafar; a hodgepodge California spiritualism drawing in equal measures from Native American, Moroccan, and Indian religious traditions and millennial Christian visions; 1950s pinup culture (Betty Page was one of the reigning icons at Fuck!) and fashion of the new “gay nineties” (Jean Paul Gaultier came to the club with his posse, and included a performer in one of his photoshoots). At once the site of playful perversion and serious politics, safe sex and barebacking advocacies, body mutilation and muscle worship, disco shamanism and high art, Fuck! drew activists and gawkers, druggies and vegan health junkies, sexual outlaws and cultural pundits.

Figure 6: Native American-inspired artwork for publicity material, ESP.

“The evidence of experience”

How are we to reconstruct this dynamic and fluid scene from my box of flyers and fag rags, and from the dispersed private collections of photographs and publicity materials that now show up on internet sites such as Facebook and Flickr, or the website for Antebellum Gallery, Los Angeles, the site of a 2009 exhibit celebrating the twentieth anniversary of the club? How do we characterize the investments that frame such a historiographic impulse—investments that both drive and deter the task of analysis? The materiality of these print artifacts helps materialize an ephemeral past, conjuring up a set of sensual relations for the researcher: beyond a literal or even figural “reading” of this material, it becomes possible to divine a series of sensate mobilizations, to speculate on an economy of queer desires.

But who is this researcher, this cipher homo academicus? Does she have a historicity, perhaps even an ontological specificity? The question I am raising here is not merely about positionality—about who speaks of the queer past, from what vantage point, and for what purposes. Or rather, if this has to be a question of positionality, then the concept itself begs expansion beyond its textual operations to involve a corporeality that is irreducible to a disembodied speaking subject. To clarify the stakes of the question, I will pose an experiential distinction between two hypothetical researchers: while both have access to a club’s publicity materials, photographs, and perhaps even video footage, and have interviewed the organizers and patrons, only one of them had the opportunity to visit the club while it lasted. Is it possible to posit and sustain a fundamental difference between the historiographic projects of the two researchers? Does it matter that one’s “position” is mediated through material artifacts and testimonies, while the other’s “position” takes shape via a further level of mediation provided by his own body, his embodied memories? How, to bluntly spell out the difference, might the creases and sweat stains on old club flyers, callously crumpled and shoved into one’s jeans pocket on a night two decades ago, matter now?

Right about the time I was spending my Sunday nights at Club Fuck! I came across a new, by now seminal, piece by historian Joan Scott on the problems of writing histories of difference. Addressing a range of challenges faced by minority groups, including queer visibility, Scott elegantly dissected the tendency to fall back on the sheer “evidence of experience” as an irrefutable register of difference, stressing that we still need language to comprehend and communicate all experience. In spite of her compelling analysis, questions about the ir/reducibility of experience to language persisted. In the past two decades, scholarship on the body, sensation, and affect have turned increasingly to the incarnate and messy attributes of experience: attributes that appear to resist textualization, but can nevertheless be apprehended, perhaps even communicated to others, through evolving language and extra-linguistic modes of expression. In these new approaches, the body is not so much the ground for authenticating experience or stabilizing the self as it is an opening onto more immersive, granular, and sensual modes of knowing. As affective knowing tinges cognition, one’s sense of self and the world becomes more provisional, distributed, coextensive.

I have no pretensions here of offering a resolution to such persistent tensions. Instead, I place the following observations in the space between two kinds of materiality: one embodied in archival texts, and the other inhering in the human corpus. More specifically, I ask what happens when the researcher’s body intervenes in a historiographic project as concrete document. If history writing involves a series of transactions with the past, what further modulations must these transactions undergo when the researcher’s own corporeal sensations and tissue memories emerge as a parallel archive and continually stimulate, vivify, and inflect her relation to the material ephemera of queer club culture? How do the synaptic flare-ups and sensorial seepages complicate the materiality of “material archives?” While nostalgia tinges my exploration of the significance of a now-defunct club in the history of a Los Angeles queer underground, there is something more than nostalgia at stake: the elaboration of a queer historiographic method in terms of the semantic-sensorial relay between a diffuse material archive and fleeting sense-memories.

Queer Becomings

Endangered Species Productions, the collective that presented Club Fuck! and Sin-a-matic, also went by the acronym ESP. This dual invocation of ecological crises and extra-sensory perception underscored the precarity of a community besieged by AIDS, and simultaneously gestured toward the possibility of a beyond. A weekly pageant of non-normative sexualities in the heart of Silverlake’s disease-ravaged neighborhoods,[5] Club Fuck!’s resolute agenda seemed to be: exploring how to have desire in the thick of an epidemic.

Figure 7: Early Club Fuck! flyer (c. 1989).

Figure 8: Ritual demonstration, Club Fuck! Photo courtesy of Tim Caszatt.

Not surprisingly, the body took centerstage at Fuck!. Sexualized, racialized,[6] ravaged, built, adorned—the body was on display and was, literally and figuratively, up for grabs. Whether in Michelle Carr’s fetish acts (often involving a metal cage and a strap-on dildo) or in Ron Athey’s ritualistic transgressions, the proverbial “go-go dancer” of strip joints and burlesque shows, as also the priest of assorted religious denominations, was recast as an edgy performance artist. Of course, not all the dancers on the stage or the raised platforms were invested in such reflexive transformation: more often, their gyrations aimed at fostering a sexually charged atmosphere and whipping up a dance frenzy among club patrons.

Figure 9: Performance at Club Fuck! Photo courtesy of Tim Caszatt.

The publicity materials feature a range of visuals, indexing practices that were also in evidence at the club. Primitive and pagan iconographies and rituals folded seamlessly into Christian ones—as if such contamination would transport us across centuries of power play and subjectification, and return us to some long-lost arcadia. Or, perhaps, the point was to provoke, to show up the agon of modern spiritual life. Again, it was the body that served as the locus of such ambivalent negotiations of the spirit, effectively erasing the archaic divisions between the carnal and the spiritual. The body manipulation of “modern primitives” (scarring, piercing, tattooing, mummification, sewing up various body parts including lips and eyelids), and various S&M practices that tested the corporeal limits of pleasure and pain (leather and bondage scenes, spanking and whipping, hot wax application), were staple components of the performance-demonstrations at both Fuck! and Sin-a-matic. Rubber, latex, plastic, duct tape, even saran wrap—materials of everyday use, at once marking the triumph and the detritus of the industrial age—were turned into objects of fascination and fetish. Pushing against—queering—the boundaries of the normative, such practices sought to design a sensuous lifeworld and cultivate a supple mode of becoming. A speculative, queer art of living that approximated a Nietzschean fröhliche wissenschaft—a playful, amenable, gay science.

The club atmospherics congealed in large measure around an array of sonic elements. Central to these was “industrial dance music,” a genre pioneered by Wax Trax Records of Chicago and its main act, Ministry, and subsequently made a crossover phenomenon by Nine Inch Nails. This genre, in turn, had its roots in European industrial music of the 1970s and 1980s (Throbbing Gristle and Coil were two seminal acts): it had a distinctively “conceptual sound art” sensibility, inspired as it was by the drone, clang, and grind of British and German factory-town soundscapes.[7]

Figure 10: Fetishizing an apocalyptic future, Fetish Ball flyer.

What had been denounced widely as noise pollution, dehumanizing urban living conditions, was thus transformed into a veritable strum und drang of modern existence—strangely appealing and invigorating, its vital fabric. This reframing of the industrial as neo-vitalist energy had contingent implications for Club Fuck!, although the connections were never quite fully worked out, remaining primarily allusive. The hypnotic beats of both the early minimalist works and the more lush and layered trance numbers induced the urge to move on the dance floor, which sometimes turned into an animated mosh pit. This vibrant scene was a far cry from the images of wasted bodies in the pre-cocktail years, even as some of the club’s original instigators were succumbing to the disease. As the publicity materials declared resolutely, the club was for a new breed of “industrial-strength queers” who wanted to shake off the precarity of the AIDS crisis to reemerge as resilient social subjects, unapologetic about the continuing centrality of atypical sexual mores in their lives. But the moniker “industrial” also invoked the sense of “commercial” and “large-scale,” signaling a desire to not remain in the margins, to not fall into the trap of espousing a radical alterity. It was as if Club Fuck! wanted to infiltrate the mainstream, to recalibrate that mainstream from within.

The other significant musical component came from the emerging domain of “world music.” This utterly reified category conflated the rhythms and melodies from the entire non-Anglophone world, finally “discovered” at the end of the twentieth century by Anglo-American musicians and impresarios such as Paul Simon, Peter Gabriel, and David Byrne.[8] It provided the acoustic cognate of exoticized rituals such as body piercing and inking. Even as the music, like the body primitivism, was getting commercialized through its global transmission, in the electric space of Club Fuck! it rang out as a clarion call, heralding the possibility of a sensory-imaginative utopia.

Perhaps the most affirmative aspect of the club was its underlying and somewhat quixotic fantasy of a social body. Fuck! solicited a plastic recalibration of the body’s relation to its surroundings, to other bodies. Beyond the twin axes of exhibitionism and voyeurism— proclivities conspicuous in the performers, the ebullient dancers, and the captivated onlookers—the club space induced a compelling and collective participatory urge. As the dancing bodies surrendered to the seductive tyranny of the beat, as they rode the melodic gradients and dynamic undulations, every gesture became an invitation to the neighboring bodies. As often a carnal incitement as a call for an affectual inter-corporeality, such gestures elicited primal resonances and responses that seemed to continually realign bodily volumes and contours.

And on some occasions, such realignments seemed to fall in place as a dancing, desiring communal corporeality shimmered into existence. The thick smoke from the fog machine, its opacity oddly enhanced by the strobe lights and laser rays slicing through it, enveloped the dancers in a dense haze: an illuminated ectoplasmic medium filling the spaces between bodies, binding them as they moved to Eon’s propulsive ditty, “The Spice Must Flow.” Congealing around the ripple of intensities traversing the bodies of dancers who had bracketed their habitual individualities and turned willingly into modulated dividuals, the club became one pulsating, frolicking presence.

On very hot summer nights, as a few hundred ecstatic bodies moved to the compulsive beats in the narrow space of Basgo’s Disco, the dancers’ sweat evaporated and then condensed in the cold blasts from the air ducts, showing up as beads of moisture deposited on the bar counter and the walls. On those nights, one felt as if a collective body had somehow transpired, leaving wondrous evidence of its evanescent becoming.

For all their encouragement and support over the years, I thank the late Miguel Beristain, Lucy Burns, Conerly Casey, Jennifer Doyle, Alison Fraunhar, Bishnupriya Ghosh, Lucas Hilderbrand, Walter Kehr, Jim Moran, Jose Munoz, Josh Neves, Laurence Padua, Lynn Spigel, the late James Stone, and Joe Wlodarz. A special thanks to Tim Caszatt, without whose help this piece would never have been written.

Notes

[1] Even Le Barcito has disappeared with the rapid gentrification of the strip. The current iteration, an upscale restaurant-bar, hasken on the old name Black Cat in a nod to civic history, while also eradicating its plebian queer roots.

[2] “The Best Fuck in Town,” L.A. Weekly, April 1991.

[3] Mark Ehrman, “Nonconformist Fun,” Los Angeles Times, 10 January 1993.

[4] This scene is the subject of the gorgeous, evocative short Miguel (Walter Kehr and Markus Janowski, 1996). See Miguel.

[5] It was around this time that I attended the premiere of Peter Friedman and Tom Joslin’s stunning documentary, Silverlake Life: A View From Here (1993) at the Vista Theater, just down the road from Club Fuck!. That event was memorable not only for the film’s devastating content, but also for its refusal to remain enframed on screen: at some point during the screening, I became acutely aware of the local audience’s deep immersion in the narrative because of similar, painfully resonant experiences of suffering and loss—past, ongoing, or imminent.

[6] The racial profile of the club’s clientele was predominantly White, with a fair presence of Latinos and Asian-Americans. While at least two members of the club’s inner circle were African-American, they remained conspicuous precisely because of the general absence of their community. This absence had to do with the club’s characteristic musical sensibilities, corporeal idioms, and cultural references. If African American bodies and ideolects were embraced, they were also fetishized. Seen out of context, this might produce unease and raise the kind of debates raging at the time around the work of Robert Mapplethorpe. But within the club’s overarching culture of affirmative fetishization, this was all quite kosher.

[7] Andrea Juno and V. Vale, eds. Industrial Culture Handbook: Re/Search #6/7 (San Francisco: Re/Search Publications, 1983).

[8] David Byrne disavowed this catch-all, residual “genre” in his piece, “I hate World Music,” The New York Times, 3 October 1999. It is reproduced here: "I Hate World Music.

Bhaskar Sarkar is an associate professor of film and media studies at UC Santa Barbara. His primary research interests include post-colonial media theory, political economy of global media, and history and memory. Sarkar is the author of Mourning the Nation: Indian Cinema in the Wake of Partition (Duke University Press, 2009), a critical exploration of the cinematic traces of a particular historical trauma. He has published essays on philosophies of visuality and Indian and Chinese popular cinemas in anthologies and journals such as Quarterly Review of Film and Video, Rethinking History: Theory and Practice, and New Review of Film and Television Studies.