Haunting Mise-en-scene: The Contours of the Holocaust

by Aaron Kerner

[ PDF Version ]

The Sadean hero is not a brute animal beast, but a pale, cold-blooded intellectual much more alienated from the true pleasure of the flesh than is the prudish, inhibited lover, a man of reason enslaved to the amor intellectualis diaboli—what gives pleasure to him (or her) is not sexuality as such, but the activity of outstripping rational civilization by its own means, by way of thinking (and practising) to the end the consequences of its logic.

-Slavoj Zizek [1]

Where have I seen this before? While watching Eli Roth’s 2005 film Hostel I was suddenly captivated by the image before me, and it had very little to do with the grim exhibition of torture (Josh’s torturer drilling holes into his hapless victim), rather the sparse concrete room reminded me of something, but what? Then it came to me in an instant, I had seen this space before, I had walked through it, or at the very least a space very reminiscent of what I was seeing in Hostel—Crematorium I in the main camp of Auschwitz. While visiting The Archives of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum I explored the Auschwitz complex. Of course one of the most charged sites in the main camp is the gas chamber and crematorium, the only one remaining intact (the gas chambers and crematoria at Birkenau were all destroyed). What is perhaps most striking about the site is its sparseness—the bare concrete exhibiting the distinct patina of age. For me personally, a small detail caught my attention, a roughly chiseled out square window (actually I’m not even sure what it’s function was—or if it was a postwar artifact), and I was startled to find it in Hostel. Like Crematorium I, the torture chamber in Hostel is decidedly sparse, the walls bearing the characteristic wear of age, even a rectangular centrally placed window, and that uncanny roughly carved out square opening.

I could potentially locate other instances of personal memory pertaining to Holocaust sites that find some resonance with the mise-en-scene of Torture Porn, an exercise that I might find personally fascinating, but I suspect far less so for the reader. Instead, I will identify some of the generic tropes that intersect with the cultural memory of the Holocaust—or even more accurately, our recollection of how that event has been represented in narrative cinema, something that should not be confused with the event itself. Indeed, the sharp visceral resonance of Torture Porn owes something not only to the explicit display of mutilated bodies and vivid depictions of human suffering, but also to the settings that follow the contours of the “concentrationary imaginary.”[2] In fact, and this might not seem apparent at first glance, the visual traces of the Holocaust are one of the hallmarks of the genre. Film critic David Edelstein coined the term “Torture Porn”; it first appeared in the title of his article, “Now Playing at Your Local Multiplex: Torture Porn,” which was published in the January 28, 2006 issue of New York Magazine.[3] In the end though, while the genre certainly resonates with the iconography of the Holocaust, I suspect that Torture Porn says more about our contemporary context than it does about anything else.

There are several distinct features of the genre: victims are typically confined or imprisoned in some fashion; victims are not just impaled or cut, they are frequently dismembered or mutilated; victims are tortured, not merely subjected to savage physical brutality, but also tormented emotionally and psychologically; on occasion victims are compelled to perpetrate acts of violence against others in a bid to save their own lives, faced with some sort of grievous choice usually involving bodily mutilation. To be abundantly clear, I am in no way arguing that the genre of Torture Porn is directly related to the Holocaust (the event itself). Instead, I argue that, intentionally or not, Torture Porn appears to be drawing from the history/memory of the Holocaust’s representation, plundering our visual culture for hyperbolic affect.

The perpetrators in Torture Porn are usually very intelligent, cool, calm, and collected. While malice might be a motivating factor, the perpetrator usually remains composed. Perpetrators do not act capriciously, but rather meticulously execute their plans; everything is premeditated. Just as with de Sade’s libertines, perpetrators establish and are governed by a set of rules, frequently manifesting as some sort of game.[4] Furthermore, the crafting of torture by the sadist is designed to secure his or her own safety, and thus violence is most often limited to a hermetic environment.

Tom Six’s 2009 film The Human Centipede (First Sequence) (Netherlands) embodies the sadistic trope, as it is frequently coupled with the medicalization of the horror genre. The antagonist of the film, Dr. Josef Heiter (Deiter Laser), is a medical doctor, but unlike many of the perpetrators in Torture Porn, Heiter is more inclined to fly into a rage. He is nevertheless, for the most part, the icy sadist we commonly find in other films of the genre. The character is drawn from the cultural memory of Nazi medical experimentation, namely the figure of Doctor Josef Mengele. Heiter’s home is decorated with paintings and photographs of grotesque bodies and Siamese Twins. We discover that although retired, Heiter specializes in separating Siamese Twins. This corresponds to Mengele’s interest in twins because of their unique potential as experimental subjects. Heiter’s relatively secluded estate calls to mind the seclusion of the concentration camp, and offers an enclosed space characteristic of the sadistic disposition. The doctor also dons many of the fetishistic tropes associated with the SS—jackboots and a riding crop for instance. Heiter confines hapless victims in his medical lab (conveniently located in his basement), and realizes his grotesque fantasy of creating a human centipede by surgically connecting—anus to mouth—three individuals. While Heiter’s disturbed vision of creating a new plaything may strike the viewer as insane, Heiter’s desire to create a new creature recalls Mengele’s pursuit of manufacturing racial perfection.

The Human Centipede

There are medical elements to the traps found in the Saw franchise as well; the traps are intimately related to biology, in many instances involving the splaying open of flesh and bone, and the destruction of the body. The antagonist of the series, Jigsaw (Tobin Bell), is a sadist par excellence—calculated and measured in the delivery of his own form of justice. Each trap is designed to match the subject’s apparent transgression, and is explicitly designed so that a subject might extricate himself or herself if they precisely follow the rules of the “game.” The traps are frequently designed to test a subject’s capacity to endure pain; in most cases the devices exhibit the patina of age, rust, and wear, but are nevertheless meticulously engineered to execute a punishment at the appointed time. The ghastly nature of the traps coupled with their precise engineering conjures to mind the architecture of death in the Nazi concentration camp—evidence of a systematized regime that necessitated the careful crafting of infrastructure to execute the Final Solution (e.g., rail systems and time schedules, design of gas chambers, and systems to dispose of corpses).

Three of the traps in the franchise specifically reference the Holocaust imaginary. Much of Darren Lynn Bousman’s 2005 film Saw II unfolds in an abandoned house—hermetically sealed with eight “players” trapped inside. The house is filled with a nerve agent, and the test given to the characters is to retrieve syringes hidden throughout the house containing an antidote. Failing to locate the antidote means a slow death. The house itself effectively becomes a gas chamber (Kevin Greutert’s 2010 installment Saw 3D: the Final Chapter actually includes a gas chamber). While many are aware of the gas chambers at Auschwitz and other death camps, a lesser known early prototype was constructed in the Auschwitz complex: a small 300 square-foot red brick structure—dubbed the “Little Red House”—which began to operate in March of 1942. Saw II’s idea of transforming a house into an execution chamber has a certain uncanny resonance with this early design.

Additionally, Bousman’s film also includes a crematorium trap. Obi Tate, his closely cropped hair reminiscent of a concentration camp internee, crawls into the oven to retrieve two syringes hanging at the far end of the furnace. (The Saw videogame also includes this trap, and its rendering—constructed of bricks—evokes the death camp crematorium.) When Tate pulls on the syringe, the oven door shuts and the furnace ignites. Fellow characters attempt to open the door to no avail; finally, a glass portal at the far end is broken allowing Obi to partially extricate himself before dying. The burned lifeless body, dangling from the furnace, calls to mind the ghastly images of burned bodies that Allied forces discovered when German troops beat a hasty retreat.[5]

Saw II; Memory of the Camps

Hungarian filmmaker István Szabó’s 1999 film Sunshine includes one of the most disturbing depictions of Holocaust torture, and Bousman’s 2006 film Saw III lifts it outright. Szabó focuses on the Sonnenshein family of assimilated Hungarian Jews. Adam Sonnenshein (Ralph Fiennes)[6] changes the family name to Sors—something more Hungarian—and wins the gold medal at the 1936 Berlin Olympics in fencing. Initially exempt from the anti-Jewish laws enacted in Hungary, owing to Adam’s gold medal and the family’s service to the Hungarian monarch, the family nevertheless is swept up in the brewing anti-Semitism of the period. Adam and his son Ivan are eventually sent to a Hungarian labor camp, and in one of the most harrowing depictions of torture in the film, Adam refuses to acknowledge his Jewish identity. A sadistic Hungarian camp guard calls Adam to the front of the assembled internees; repeatedly the camp guard asks, “Who are you?” and inquires why he’s wearing a white exemption band around his arm instead of the Jewish star. Despite being slapped around he says, “I am Dr. Adam Sors, officer of the Hungarian Army.” And, “I am the national fencing champion.” And, “I am an Olympic gold medalist.” Each response enrages the guard, and brings increasingly more severe blows. Ordered to strip, Adam is bound and beaten, but continues to espouse his national credentials. Finally, hung up in a tree, he is hosed down with water until his body is fully encased in ice.

Sunshine

In Saw III Jigsaw enlists Jeff in a series of games where he is given the opportunity of either saving or punishing the people he holds accountable for the death of his son. Jeff finds Danica Scott in a walk-in freezer, strung up and naked. Jets of water periodically douse Danica; she was the only eyewitness that could have prosecuted the individual responsible for hitting and killing Jeff’s son. Jigsaw’s accomplice places a key at the back of the room that will allow Jeff to free Danica from her bindings, but the key is hard to reach and Jeff’s hesitancy to act promptly ultimately leads to the woman’s death—frozen solid like Sors.

Saw III

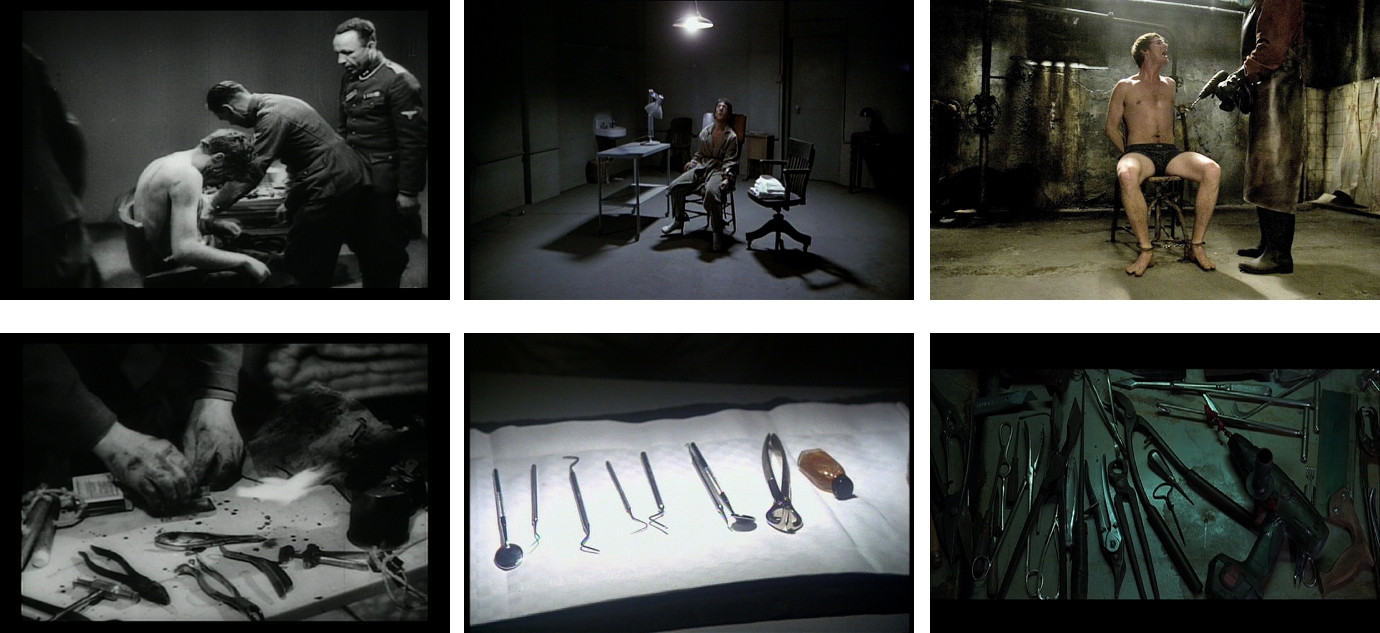

Eli Roth’s Hostel films (2005 and 2007) trade more explicitly in the Holocaust imaginary. The visual and narrative motifs find a clear cinematic heritage in films like Roberto Rossellini’s 1945 film Rome, Open City, and John Schlesinger’s 1976 film Marathon Man.[7] Both feature an SS-man torturing a subject, strapped to a chair in a sparse non-descript room. The exhibition of the instruments of torture, from an objective shot, intends to fill the spectator with dread-filled anticipation—how will these instruments be utilized to induce pain in the bound subject?

Two stills each from Rome, Open City (L); Marathon Man; Hostel (R)

In the Hostel films a crime syndicate, Elite Hunting, caters to the sadistic taste of the rich. The syndicate re-purposes an abandoned factory as a complete in-house torture facility. Abducting tourists from a Slovakian hostel, Elite Hunting then sells the victims to an international clientele, who come to the torture facility, as if to an exclusive brothel, to enact their sadistic fantasies. The emblem of the torture syndicate is a bloodhound. All the sadistic clients—and presumably all members of the syndicate—have the syndicate’s emblem tattooed on their left arm (in Hostel: Part II the tattoo is placed elsewhere). At first glance the moniker in itself is nothing special; however, this implicitly relates the members of the syndicate to the SS, many of whom also had tattoos on their left underarm, indicating their affiliation with the Waffen-SS and the individual’s blood-type. Adopting the bloodhound as the tattooed emblem meets up with the tattooed blood-type of the SS.

The torture factory is topped with a large smokestack, which echoes the silhouette of the concentration camp. In addition, when a rich client is finished the Elite Hunting staff clean up: a large hunched-backed man hauls bodies (or just body parts) into a room where they are then butchered into smaller pieces, and finally tossed into a furnace. The oven, the smokestack, and the piles of mutilated corpses are hard, if not impossible, to separate from the images that we associate with the concentration camp. The furnace is precisely where Roth’s 2007 film Hostel: Part II begins; an unseen undertaker rummages through a victim’s belongings, setting aside valuables, and casting other personal possessions—clothing, a diary, photographs and postcards—into the flames. This is very reminiscent of the early scenes in Ka Tzetnik 135633’s Holocaust novel House of Dolls, which also includes descriptions of discarding photographs, letters and other personal items, while retaining anything of monetary value.[8] This sorting of the victims’ belongings, and the discarding of personal effects resonates with the Nazis plundering of loot collected from deportees.

The seemingly banal space, the decor, and the instruments displayed before the victim are charged with a wholly different character, rather nefarious in fact. The everyday objects—a drill, a dentist’s pick, a chair—become weapons when recontextualized in the framework of torture. This undoing of a stable order is designed to evoke dread in the character subjected to torture and in the spectator.[9] “The appearance of these common domestic objects . . . ” in the discourse of torture, as Elaine Scarry observes, draws on the fact that “much of our awareness of Germany in the 1940s is attached to the words ‘ovens,’ ‘showers,’ ‘lampshades,’ and ‘soap.’”[10]

The signature enclosed space in Torture Porn films corresponds to the sadist’s reliance on a hermitic universe, where within a strictly defined space nothing is abject. And from this perspective it is possible to see how the torture chamber in Torture Porn films is an overdetermined site; alluding to the concentrationary imaginary, the libertine’s hermetic spaces in de Sade’s novels, and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s rendition of those in his 1975 film Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom.[11] The torture chamber in the Torture Porn genre, though, is frequently dank; dark, damp spaces colored in the various shades of fecal matter. And in the fecal palette the torture chamber in Torture Porn butts up against the conceptualization of the concentration camp, which has been referred to as anus mundi—the asshole of the world. (Notably, much of the action in the first Saw film takes place in a bathroom.)

The vestiges of the Holocaust haunt the mise-en-scene of Torture Porn. If this motif were an isolated instance, one might chalk it up as the idiosyncratic visual design of an individual film; however, when reviewing the spectrum of films in the horror genre of this new century, one discovers a strange pattern of Holocaust appropriations. So what are we to make of this? And why does the iconography of the Holocaust so thoroughly penetrate the post-9/11 genre of Torture Porn?I argue that where the tradition of Holocaust films clearly demarcated the world into realms of good and evil, in the post-9/11 era this Manichean worldview rings false. While the Bush administration tried to make Al Qaeda play Indian to our cowboy, such narratives fail to resonate. And this is precisely where Torture Porn films do resonate, negotiating an American sadistic disposition that has become apparent, given John Yoo’s “Torture Memo,” so-called “enhanced interrogation techniques,” renditions, CIA Black Sites, Donald Rumsfeld’s bald-faced contortion of language to justify American activities, sadistic treatment of prisoners at Bagram Air Base, Guantánamo Bay Prison, and the photographs that emerged from Abu Ghraib Prison. It’s difficult to argue that the United States occupies the moral high ground given these actions, its foreign policy, and its execution of the so-called War on Terrorism. Furthermore, one of the questions asked in the immediate wake of the 9/11 attacks was: Why do they hate us so much? The response was deafening silence; the American Government never answered this question head-on, probably because of the unflattering answers that would likely emerge.

Torture Porn negotiates the reality of American sadism that we have failed to come to terms with. Does this mean that we are no better than the Nazi regime? No, of course not, but rather that the clarity between good and evil is not as nicely demarcated as we might care to imagine it. Torture Porn places in bas-relief the conflicting visions we have of ourselves. While on the one hand we might still desperately cling to a nostalgic celebration of good guys versus bad guys, Torture Porn negotiates a less than flattering image of America—it exhibits a much more confusing and complex conflict where the American administration justifies torture (not to mention the toppling of governments under false pretense) in order to keep us safe. Furthermore, there is a certain revelry in the pro(an)tagonists of some of these films—think of Jigsaw, or in the world of television, Jack Bauer and Dexter Morgan. All of these figures dispense with ethics for the sake of “justice,” to make the world a safer place, to rid the world of scum. And at the end of the day, isn’t that what most people want, regardless of how it might be achieved? Does Torture Porn then envision—as sick as it might be—the clearest picture of what we want, or perhaps even who we are? I’m leaning towards the affirmative.

Notes

[1] Slavoj Zizek, “Kant with (or against) Sade,” in Elizabeth and Edmond Wright, eds., The Zizek Reader (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999), 287.

[2] This rhetorical strategy is part of a renewed interest in Holocaust scholarship, generations removed from the event, aiming to locate affinities in representing the catastrophic, or traumatic experience (e.g., the post-colonial experience). This is evident in, for example, the seminar series Research Project Concentrationary Memories at the University of Leeds, organized by Griselda Pollock and Max Silverman. See for example Max Silverman’s work, “Interconnected Histories: Holocaust and Empire in the Cultural Imaginary,” where he writes regarding this new trend in research: “It is . . . an attempt to unearth an overlapping vocabulary, lexicon, imagery, aesthetic and, ultimately, history, shared by representations of colonialism and the Holocaust” Max Silverman, “Interconnected Histories: Holocaust and Empire in the Cultural Imaginary,” French Studies vol. 62, no. 4 (October 2008): p. 420.

[3] David Edelstein, “Now Playing At Your Local Multiplex: Torture Porn,” New York Magazine vol. 39, no. 4 (2006): 63-64.

[4] For more on the philosophy of libertinage see in addition to the Zizek chapter previously mentioned above: Pierre Klossowski’s Sade My Neighbour (London: Quartet Encounters, 1991); Slavoj Zizek’s “Much Ado about a Thing,” found in For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor (London: Verso, 1991); Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s, “Juliette, or Enlightenment and Morality,” in their co-authored Dialectic of Enlightenment (New York: Continuum, 1994); and finally of course de Sade himself—for perhaps the most transparent exhibition of the philosophy of libertinage see his Philosophy in the Bedroom which is published as Three Complete Novels: Justine, Philosophy in the Bedroom, and Other Writing (London: Arrow Books Limited, 1991).

[5] See for example the haunting images in Memory of the Camps (1984) created under the supervision of British media magnate Sidney Bernstein; a documentary culled together with footage shot by Allied forces immediately following the liberation of Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, Dachau, Ebensee, Ludwigslust, Mauthausen, Ohrdruf, and other camps. The film is commonly, but mistakenly attributed to Alfred Hitchcock.

[6] As if to atone for his role as Amon Goeth in Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film Schindler’s List, Ralph Fiennes plays three characters in Szabó’s film—successive generations of the Sonnenshein family.

[7] I discuss Rome, Open City and Marathon Man at greater length in my book Film and the Holocaust (New York: Continuum, 2011), 168-173. Also see related chapters: “Sadism and Sexual Deviance,” “Pornography and Exploitation,” and “The Horror Genre and the Holocaust.”

[8] Ka Tzetnik 135633 was the pseudonym for Yehiel De-Nur, who took his concentration camp numerical identification as his penname.

[9] In Elaine Scarry’s seminal book on torture, The Body in Pain, she discusses this precise issue: “The room, both in its structure and its content, is converted into a weapon, deconverted, undone. Made to participate in the annihilation of the prisoners, made to demonstrate that everything is a weapon, the objects themselves, and with them the fact of civilization, are annihilated: there is no wall, no window, no door, no bathtub, no refrigerator, no chair, no bed.” Rather there are only objects that have the potential to execute pain. Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: the making and unmaking of the world (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 41.

[10] Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: the making and unmaking of the world (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 41.

[11] In de Sade’s novel, The 120 Days of Sodom, the four libertines abduct an equal number of boys and girls that are then taken to a remote and secluded chateau where the libertines humiliate and torture them. Sade continually ramps up the violence, before the final orgy of death. Pasolini’s film closely adapts Sade’s novel, though sets it in 1945 in the Republic of Salò, the last holdout of the Italian fascist regime, in the northern region of the country. The film can be read as an allegory of the Holocaust.

Aaron Kerner is an Associate Professor in the SFSU Cinema Department, where he has taught since 2003; prior to this he was a lecturer in the History of Art and Visual Culture Department at UC Santa Cruz. He was the recipient of, among other things, an NEA grant for his exhibition Reconstructing Memories (2006). In 2011 he published Film and the Holocaust (Continuum)—an extensive survey of narrative, documentary and experimental representations of the Holocaust. He is currently working on a range of subjects in and around the concept of ugliness and disgust (e.g., Torture Porn, Butoh, and cinema).

Media Fields Journal

Media Fields Journal