Visualizing Amnesia: Memory and Space in the Photography of Shanghai’s “New Village”

by Lu Pan

[ PDF Version ]

The end of the Cultural Revolution came with a series of dramatic socioeconomic and cultural transformations under Deng Xiaoping’s open door policy. Since then, China’s cultural production has gradually gained more freedom. However, a contradictory situation emerged after the crackdown of the 1989 student movement at Tiananmen Square. On the one hand, China remains under the rule of the Communist Party and therefore state intervention still holds a tight rein on the realm of cultural industry. On the other hand, the post-1989 Chinese society largely embraces consumerism as the predominant ideology. Therefore, both clichés of socialist propaganda and distinctly individualistic works characterize visual representations of today’s China. The narratives conveyed by the images of the new generation of photographers, whose life experiences and value systems have been formed under such contradictory circumstances, often display a tension-ridden exploration of the present and past, the self and the other, the collective and individual.

To illustrate this tension in contemporary Chinese society, this essay examines one case study of post-1989 image making: the images of the Worker’s New Village from the communist revolutionary era. Based on the Soviet model of the residential units for the working class, nine Worker’s New Villages were built in China’s biggest city, Shanghai in 1951 and 1952. By the end of 1958, the number of "Worker’s New Villages" had reached 201 as almost six hundred thousand workers and their families moved from decrepit houses to the brand new concrete buildings.[1] However, after 1978, the introduction of the “socialist market economy” and the consequent change of social and economic structure have altered the destiny of architectural legacies from the previous era, including Workers' New Villages. The no longer modern cubic blocks of concrete disappeared from the center stage of Shanghai’s urban landscape. The symbolic meaning of the term “New Village”, as the triumph of the working class’ political privilege in the state, has been lost. In a time when globalized urban forms crystallize the country’s new ideology of modernization, the New Villages are disappearing from the mainstream visual representations of Chinese cities. Here I take this invisibility as a form of public amnesia. In Shanghai, this public amnesia is particularly conspicuous when contrasted with the city’s predominant image as a metropolis of high prosperous capitalist modernity in the 1930s and 40s.

Memory of Space: New Village from Two Angles

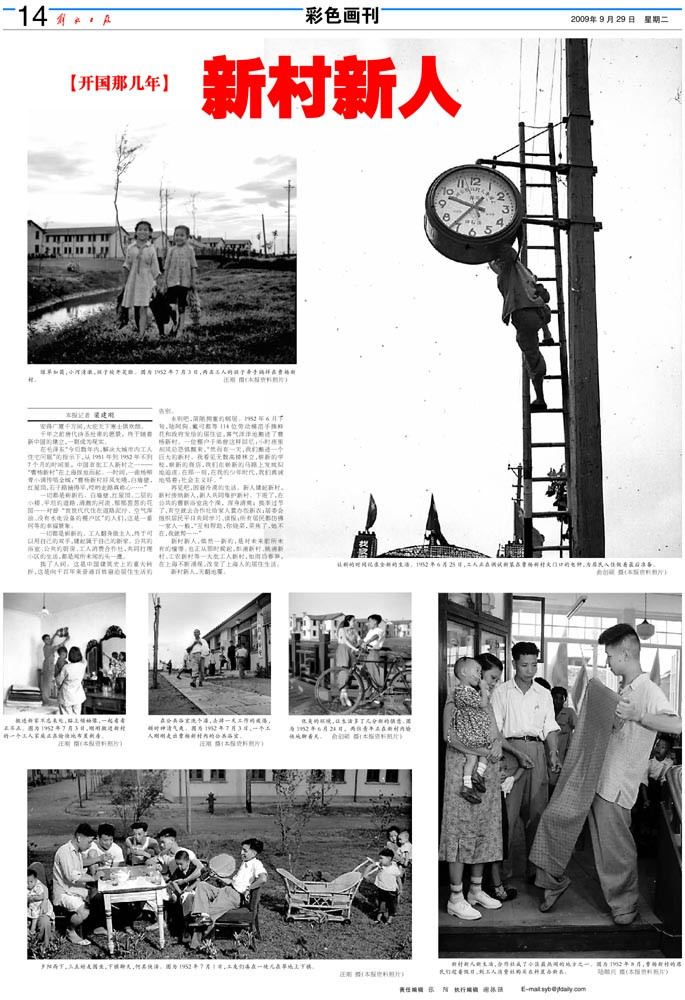

This brief study focuses on how memories of New Village spaces are addressed in different photographic representations. Two sources of image (re)production of Shanghai’s New Villages from the past five years caught my attention. The first, a group of photos of Caoyang New Village, the first new village constructed in Shanghai, appeared in the Communist Party-owned newspaper Jiefang [Liberation] Daily (Jie Fang Ri Bao) on September 29, 2009. Released shortly before the sixtieth anniversary of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 2009, an illustrated page named “Early years of the PRC” presents seven archival photos taken in the 1950s. They show scenes of everyday life of residents of the Caoyang New Village. The second source is a photography collection called New Village (2006), containing more than five hundred pictures by a Shanghai-based independent art group called “Bird Head” (niao tou). Taken by the group’s two young members, Song Tao (b. 1979) and Ji Weiyu (b. 1980), this collection also illustrates the everyday life of the neighborhood where the two artists grew up: Xueye New Villages in Shanghai’s Pudong New District. By comparing these two groups of images of New Village space, I explore the different memory narratives of New Villages through the texts and contexts of photographic visualization. Here, photography produces not only, according to Henri Lefebvre, “representations of space”, but a “representational space” or “spaces of representation.” In this case, the space is not only the representation/carrier of memory’s message but also participates actively in the making of memory.

Figure 1. Source: Jiefang Daily September 29, 2009

Body and Space

The memory narratives in these groups of New Village images can be contrasted in several ways. First, the camera eye in the two series shows a discrepancy in the relationship between the body of the dwellers of the New Village and the Village space. In Jiefang Daily’s New Village, the depiction of the bodies engages in a coherent and complete form for the reader’s recognition and perception. (Figure 1) All shot between late June and early July 1952, the photos included here try to capture a uniform narrative invoked by the newly constructed neighborhood: one of joy and ease. Most children and adults are smiling, standing, sitting, or walking with an upright posture. The highly orchestrated images of two school girls walking alongside a creek (Figure 2) and a young couple talking happily on a bridge correspond to the photographic style in 1950s–1960s China when nearly all visual representations served the purpose of political propaganda. The other four photos—in which neighbors entertain themselves playing chess (Figure 3), a couple shops in the communist cooperative, a man walks out of a public bathhouse, and a family decorates their new apartment—all depict a relaxing and amiable atmosphere of everyday leisure. The only image that depicts labor shows a man standing high on a ladder to adjust the electric clock in the public space, a final preparation for new residents moving into the New Village.

Figure 2. Source: Jiefang Daily September 29, 2009

Figure 3. Source: Jiefang Daily September 29, 2009

However, the space and the living bodies are seen to be separate. The New Village seems static and timeless, as a stage for life/live performance. The bodies are footnotes for the space, which was abstracted to symbolize an idea, an ideology or a paradigm of life. Cultural critic Zhang Hong describes the puritan collective lifestyle that was formed by the living space of New Villages. In this space, “residents were grouped according to blocks and buildings, sitting on footstools and listening to newspapers read aloud by a special newspaper reader. At weekends, when the bell was ringed as a reminder, residents would willingly begin to clean the public area of new villages.”[2] The narrative approximates the camera eye, which poses the bodies as an embodiment of the space and its ideology.Interestingly, while Michelangelo Antonioni was invited by the Chinese government to shoot the beauty of the Workers’ New Village in Shanghai, the place, nevertheless, is seen in the film Chung Kuo,Cina (Italy,1972) in a ghostly austerity. Without a lively flow of people in their everyday life, the village looks empty and barely human. The camera eye moves around the shanty houses as opposed to the New Village, accompanied by children’s impassioned, lusty singing in ode to the revolution in the background.

In Bird Head’s New Village, the portrayal of the body vis-à-vis space addresses another kind of communicative relationship between the two. The two models in their collection, a young man and a young woman, are seen in varied gestures and moods. Like urban flâneurs in constant search for the fragments of modern city space, the two artists try to de-familiarize the objects, spaces, people, and city that go unnoticed for being known too well. As if looking for a “reversed hallucination,” something that is always present but never seen, they re-contemplate the relation between their bodies and the space, finding that there is no difference between them. The images in New Village problematize the partition of memory, body, and space. They write in their blog “The World of Bird Head”:

It's just u! Our 6-storeyed buildings and ur fresh cement smell! u r the objects of our camera lens!

we r u, our fast built and fast destroyed 6-storeyed buildings! we laughed and cried right beside ur cold cement wall, we kissed and hugged each other here, we shouted abuse, we had bicycle ride and jaw dislocation right beside u, we stood by u proudly, shoulder to shoulder.[3]

Here the body and space mutually shape each other with their own transformative power. In the images, both space and bodies refuse to be diminished to empty, homogenous, and abstract signs of a pre-designed knowledge structure. The space is seen to be as alive as the body in forming memory, identity, and emotions. These manifesto-like claims explain why the collection of photography entitled “New Village” actually “features the artists photographing each other and various street-level detritus in dozens of deliberately un-picturesque urban locations . . . [T]he photographic medium allows them to express a unique dual identity and the work almost assumes the status of a performance documented.”[4] Taking the living bodies as an inseparable part of the space, Bird Head’s images respond to the imposed denial of this liaison. In 2007, demolition of the Xueye New Villages began to make space for the constructions of the pavilions for the Shanghai World Expo 2010. The physical destruction of the New Villages seems to wrap up its historical mission and intensifies the legitimacy of its death and the amnesia of its existence. However, for the two young artists, the New Villages are a part of their body, the Shanghai that they have known since childhood, in all four seasons, beautiful and ugly. Their claims do not aim to beautify their memory of the all too familiar city space, but still refuse to yield to the deprivation of it in the form of photography. For them, the real home city is ostracized for producing a visual spectacle that caters only to the global gaze.

Figure 4. From New Village, Bird Head. Courtesy of Song Tao and Ji Weiyi

Realities: Everyday, Ordinary and Unspectacular

Both collections of New Village images use a kind of realism, mediating realities in their own approaches. The presentation of the New Village in Jiefang Daily is predominantly marked by the norms of aesthetics, which conform themselves to a search for a rationalized telos. The newly created space is full of hope and brightness as its construction embodies the prevalent ideology of prioritizing working class people and the commitment to improve their living conditions. The changes in the urban landscape largely functioned as an important part of the formation of socialist national identity. In Zhang Hong’s observations:

the ‘New Village’ has become a unique form of modern urban space. The workers’ new villages not only instilled the utopian passion into the imaginary of urban modernity but also embodied the way of spatializing and incarnating the political utopia. The whole new village is like a micro-society, which consists of the basic mechanism and function of a society and was managed in a highly sound and ordered manner. According to the social value at that time, people who were entitled to live in Caoyang Village were authentic factory workers[5]

The images captured by the photographers of Jiefang Daily correspond to the above myth of the Workers’ New Village.

In comparison, the representation of the everyday in Bird Head’s New Village exposes no such trace of unconditional contentment towards an arranged reality. The motifs of their photos refuse to adhere to either a coherent structure or a documentary mission full of social meaning (Figure 4). As one of the leading figures of Chinese new photography, Bird Head is regarded as a typical producer of “personal photographs”, which seem to focus exclusively on very limited themes of everyday trivialities. Unlike the Jiefang Daily’s New Village, Bird Head’s visual rendition of the utopian neighborhood is imbued with randomness. Both in color or monochrome, their semi-autobiographical images unfold in the manner of Michel de Certeau’s anti-Concept-city, a “condition of its own possibility—space itself—to be forgotten: space thus becomes the blind spot in a scientific and political technology.”[6] Images of a tree, a messy room, an ATM, a door, a statue on the street, wrecked houses, a bridge, a dusted bike, a lift, a dog, a fountain, and the neighborhood they live in are mundane, unspectacular, banal, and to good effect (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. From New Village, Bird Head. Courtesy of Song Tao and Ji Weiyi

Figure 6. From New Village, Bird Head. Courtesy of Song Tao and Ji Weiyi

Bird Head’s capturing of memories of everyday life serves as a powerful means of articulating the significance of ordinariness and meaninglessness. The banality of object, space, and body they show in the everyday life of the new village makes the photography become a mediator between private and collective sensorium: “it is because the photographs carry no certain meaning in themselves, because they are like images in the memory of a total stranger, that they lend themselves to any use.”[7] Growing up in the most breathtaking period of transformation that a society could undergo, Bird Head shows in their pictures an alternative version of configuring the social reality. Here, the memory of the neighborhood and its details are “knotted into the emancipatory project of uncovering the elements of subjectivity, and heightening the reflexive attitude that had been suppressed by the instrumental rationalism of the modern world.”[8]

In interviews, the two photographers describe how chance, spontaneity, and lack of reason have led them while working with the images. Yet they overtly claim to not trust the truthfulness of photography—if photography “is all about ‘deceiving,’ this then becomes a question of methods. How do you deceive? In what way is the deception suitable? Everyone is looking for a way that suits them to work. The way we used does. This is how we compile our collections.” Through the representation of their bodies in the space, photography becomes a screen, which constitutes the realities of their emotion and memory. The elimination of the partitions among these realities is precisely what they are after.[9] Through the representation of their bodies in the space, photography becomes a screen, which constitutes the realities of their emotion and memory. The elimination of the partitions among these realities is precisely what they are after.

Between Nostalgia and Amnesia

In this vein, both sets of photographic images speak to a memory of space that straddles nostalgia and counter-nostalgia, amnesia and counter-amnesia. The reproduction and re-presentation of the Caoyang New Village in the Jiefang Daily in 2009 endeavors to re-invoke the memory of the New Village when it was not yet low in the urban spatial hierarchy in Shanghai. Its re-appearance amid the celebration of China’s economic triumph under the revised socialist ideology is simultaneously nostalgic and amnesic. The nostalgia, in Svetlana Boym’s terms, is a restorative one, which “believe(s) that their project is about truth.”.[10] If nostalgia is ultimately connected to something that is present in the past and absent in the present, such restoration is as weak, if not paradoxical, as the ideology that endorses it is allegedly still valid. Here the mechanical reproduction in Benjamin’s sense tries to re-claim rather than destroy the aura of the original images. The projects of “New Village” photography as truth-witness to the actual 1950s space try to evoke the spaces’ past symbolic values in the viewer. This endeavor is set off sharply by the loss of their credibility in constituting the core national myth, as well as the underprivileged social status of the working class in the current Chinese society. The amnesia is sustained by and helps to sustain the actually obsolete national myth, in which a huge gap in the past and the present reality is glossed over. In this sense, the memory narrative of New Village in Jiefang Daily today is depoliticized and romanticized.

In comparison, the production of the everyday space in Bird Head’s New Village, despite its redemptive gestures, carefully keeps its distance from a sentimental or even reflective nostalgia, which Boym characterizes as “linger[ing] on ruins, the patina of time and history, in the dreams of another place and another time.”.[11] Bird Head’s New Village deals with the now, the very immediate present of emotions, which relate to multiple possibilities. On the one hand, the memory narrative in their works reveals the resistance against the public amnesia of New Village space. Their composition of the outdated socialist space may be understood as a counter-image to two image productions: firstly to the idealized, framed scenes of the space in the 1950s, and secondly to the iconic image of the “other Shanghai” that is overly conscious of the global gaze. Chinese scholar Gu Zheng sees revolutionary impulses in their visual expression:

[T]heir camera, as a weapon of memory, is used to resist the amnesia of the past or one-sided memory, trying to restore the erased part of history and to recover the exiled reality. Their memory is an opposing memory against the amnesia in disguise of a kind of pseudo-memory. They memorize by taking photos, but this is not nostalgia…it is a withstanding, a resolute visual revolution.[12]

On the other hand, New Village may also assert an indifference towards the images of other spaces of the New Village or of Shanghai. The New Village space in Bird Head’s photography, interestingly, doesn’t mourn the loss of time, but accepts it. Alain Badiou expounds on both affirmative and destructive forces in negation, which he calls subtraction and destruction respectively. According to Badiou, any political or artistic novelty produces a subtraction that “exists apart from the purely negative part of negation. It exists apart from destruction.[13] The resistance in New Village doesn’t turn out merely to be a denial of other images, but a creation of the artists’ own means of affirmative emotional expression, a subtraction that is indifferent to other images. The internalization of the space within their bodies thus constitutes an ambivalent attitude towards the vicissitudes of time and space. Bird Head observe the dynamics between sensation and space in their meticulous statements:

Our hearts are filled with huge amount of love and sadness. Afterwards, there are metro and light rail, crossing through Shanghai under the ground or in the sky. Time passes too quickly for us to make a revolutionary posture. No time for questions and hesitation. There’s a voice pushing us, following the boy with chestnuts, wandering aggressively and aimlessly, to witness what shadow our Shanghai will create and when the ivy will cover all the roads. [14]

Thus, in their works, the four seasons of the new village, where bright color of the blossom in the garden and the somber statues of deer in the darkness indicate a fluctuating visual re-making of the space, are depicted in a mode of diverse perceptions: tension-ridden, anxious, playful, or sarcastic. Without melancholy for the destruction of the past, the images in New Village show the new potentials flourishing in the cracks of destructive changes.

The co-existence of the two sets of images in contemporary China illustrates the tension and contradiction between the visual narrative of spatial memories of the state and those of individuals. The New Village in Jiefang Daily is constructed as a kind of standard “representation of space” in the logic of what socialist memory of China should look like. These representations, according to Henri Lefebvre, are conceived and identified by scientists and planners’ views on “what is lived and what is perceived” by the living dwellers in the space.[15] In Bird Head’s “indifferent resistance,” the New Village becomes the Lefebvrian “representational space.” This space is “directly lived through its associated images and symbols, and hence the space of ‘inhabitants’ and ‘users,’ but also of some artists and perhaps of those . . . who describe and aspire to do no more than describe. This is the dominated—and hence passively experienced—space, which the imagination seeks to change and appropriate.”[16] Their efforts expose how actual urban spatial changes become contested in social space, in which new forms of memory, identity, and subjectivity came into being. Their visual language illustrates how the space of memory in Shanghai animates the memory of space in its texts and contexts. Probably because of this unyielding but multilayered message, the works of Bird Head have found larger resonance beyond their personal context. Their rising status in the Chinese contemporary art scene and the successful circulation of their works in the international art market bring us to the following question: why are the actually peripheral spaces of the New Village able to garner attention in the art world? If art is a utopian plan left unfinished, when individuals try to blast open new meanings in the holistic façade of uniformity of spatial memory, they also gain the freedom from being forgotten, which is precisely based on their marginality.

Notes

[1] "New Residential Constructions," In The History of Shanghai Residential Constructions: Department of Shanghai Gazetteer (November 3, 2011). http://www.shtong.gov.cn/node2/node2245/node75091/node75096/index.html.

[2] Hong Zhang, “Shanghai: Metropolis of Memories and Fantasies," Tongji University Journal, Social Science Section 16, no. 6 (2005): 37–43.

[3] Birdheadworld, “Xin Cun?!” (2007), accessed November 10, 2011.

[4] John Millichap, ed., New Photography in China (Shanghai: 3030 Press, 2006), 16.

[5] Zhang, "Shanghai: Metropolis of Memories and Fantasies," 42–43.

[6] See Michael de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (University of California Press, 1984), 95.

[7] Nikos Papastergiadis, Spatial Aesthetics: Art, Place and The Everyday (London: Rivers Oram, 2006), 74.

[8] Ibid, 38.

[9] Jie Hai, “Birdhead: The Emotional Gymnastics of the Photography Guerilla,” (2010), accessed January 5, 2012. http://news.xinhuanet.com/foto/2010-09/19/c_12586329.htm

[10] Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 41.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Zheng Gu, "This Is Our Shanghai’: Birdhead’s New Village," in Cover and Penetration: Spectacle of Chinese Contemporary Photography (Beijing: China Federation of Literary and Art Circles Publishing Corporation, 2008): 162-73, 172. Author’s translation.

[13] Alain Badiou, “Destruction, Negation, Subtraction - on Pier Paolo Pasolini”, in Graduate Seminar - Art Center College of Design in Pasadena - February 6 2007, accessed April 27, 2012. http://www.lacan.com/badpas.htm

[14] Shanghart Gallery, Bird Head (2009), accessed November 10, 2011. http://www.shanghartgallery.com/galleryarchive/artists/id/51.

[15] Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1991), 39.

[16] Ibid.

Lu Pan is currently a visiting fellow in Harvard-Yenching Institute. Her PhD dissertation focuses on a comparative study of the milieus of memory, modernity, and visual culture in Shanghai and Berlin. Her major research interests include urban spatial transformation in globalization, media, and the politics of memory and global modernity.

Media Fields Journal

Media Fields Journal